Research suggests anti-inflammatory protein may trigger plaque in Alzheimer’s disease

inflammation has long been studied in Alzheimer’s, but in a counterintuitive finding reported in a new paper, University of Florida researchers have uncovered the mechanism by which anti-inflammatory processes may trigger the disease.

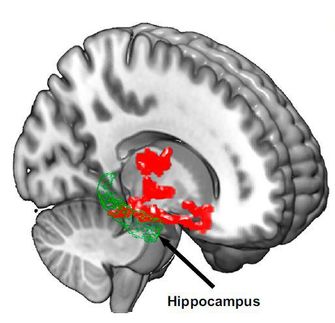

This anti-inflammatory process might actually trigger the build-up of sticky clumps of protein that form plaques in the brain. These plaques block brain cells’ ability to communicate and are a well-known characteristic of the illness.

The finding suggests that Alzheimer’s treatments might need to be tailored to patients depending on which forms of Apolipoprotein E, a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, these patients carry in their genes.

The researchers have shown that the anti-inflammatory protein interleukin 10, or IL-10, can actually increase the amount of apolipoprotein E, or APOE, protein - and thereby plaque - that accumulates in the brain of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s, according to the study, published in Neuron.

In the 1990s, researchers theorized that using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, or NSAIDs, might protect people from the onset of Alzheimer’s by dampening inflammation that released a cascade of harmful proteins. Though NSAIDs were shown to be effective in some studies, other research that evaluated a group of participants taking NSAIDs over time failed to show any clear protective benefit.

“There are many different kinds of NSAIDs,” said Todd Golde, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Center for Translational Research in Neurodegenerative Disease and the paper’s lead author. “Not all NSAIDs are equal, and it wasn’t clear what else they were doing when they were addressing their intended target.”

Previously, researchers hypothesized that a flood of proteins, called cytokines, involved in promoting inflammation in the brain contributed to the formation of plaque in Alzheimer’s disease. However, in this publication, the UF researchers provide new evidence that anti-inflammatory stimuli may actually increase plaque.

“This is another piece of evidence that overturns the long-held hypothesis that a ‘cytokine storm’ creates a self-reinforcing, neurotoxic feedback loop that promotes amyloid-beta (plaque) deposition,” said Paramita Chakrabarty, Ph.D., a member of the UF Center for Translational Research in Neurodegenerative Disease, an assistant professor in the UF College of Medicine department of neuroscience and the paper’s co-author.

The researchers said that a person’s risk of developing Alzheimer’s hinges on the relationship between IL-10 and APOE. APOE clears the cell of many different proteins, including the protein amyloid-beta, which contributes to the buildup of plaque. But there are several different forms of APOE in cells, which differ from each other by only one or two amino acids. The form called APOE4 is the largest known genetic risk factor in Alzheimer’s disease, while APOE2 is thought to be protective, Golde said.

“About 15 to 17 percent of the population has the APOE 4 allele, and about 50 percent of people with Alzheimer’s have it,” Golde said.

In this case, the authors showed that the anti-inflammatory protein IL-10 actually increases levels of all types of mouse APOE, which resembles human APOE. In the mouse model, APOE binds with amyloid-beta rather than clearing it from the brain, accelerating buildup of plaque in the brain of a mouse with Alzheimer’s. How an anti-inflammatory therapy based on IL-10 expression might alter risk for Alzheimer’s may depend on the genetic variant of APOE protein the person is carrying. If the person has an APOE4 allele the researchers predict the risk for Alzheimer’s would increase.

“In one way, this study offers additional insight into how environmental influences interacts with people’s underlying genotypes to alter their risk for diseases,” Golde said. “We know that people are exposed to various inflammatory or anti-inflammatory stimuli throughout their lives. Depending on what their genotype is, that exposure may in some cases protect them from Alzheimer’s, or, in other cases, increase their risk for Alzheimer’s.”