The inner workings of a bacterial black box caught on time-lapse video

cyanobacteria, found in just about every ecosystem on Earth, are one of the few bacteria that can create their own energy through photosynthesis and "fix" carbon – from carbon dioxide molecules – and convert it into fuel inside of miniscule compartments called carboxysomes. Using a pioneering visualization method, researchers from the University of California, Berkeley and the Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE JGI) made what are, in effect, movies of this complex and vital cellular machinery being assembled inside living cells. They observed that bacteria build these internal compartments in a way never seen in plant, animal and other eukaryotic cells.

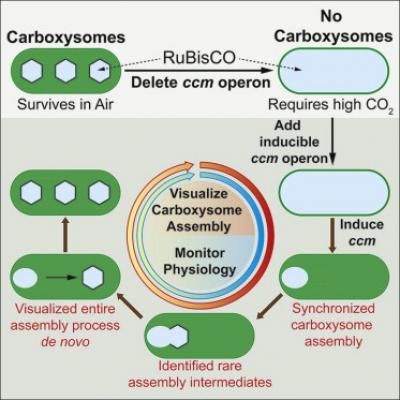

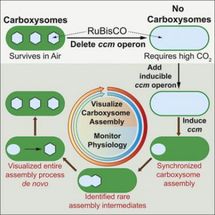

This figure demonstrates the steps researchers took to visualize carboxysome assembly. The critical genes (ccm operon) is deleted, which leads to a generation of cyanobacteria with no carboxysomes. These bacteria require high CO2 levels to survive. When the missing genes were introduced, researchers were able to watch rarely seen intermediate steps of carboxysome assembly.

Elsevier

For the first time, researchers were able to watch cyanobacteria make their critical carbon-fixing carboxysomes inside living cells using a pioneering visualization technique.

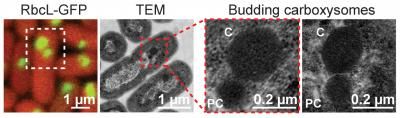

Images by Jeffrey Cameron and Cheryl Kerfeld (far left) and Susan Bernstein and Cheryl Kerfeld (center images and far right image).

"The carboxysome, unlike eukaryotic organelles, assembles from the inside out," said senior author Cheryl Kerfeld, formerly of the DOE JGI, now at Michigan State University and UC Berkeley. The findings in the journal Cell, will illuminate bacterial physiology and may also influence nanotechnology development.

Although cyanobacteria are often called blue-green algae, that name is a misnomer since algae have complex membrane-bound compartments called organelles -- including chloroplasts -- which carry out photosynthesis, while cyanobacteria, like all other bacteria, lack membrane-bound organelles. Much of their cellular machinery – including their DNA – floats in the cell's cytoplasm unconstrained by membranes. However, they do have rudimentary microcompartments where some specialized tasks happen.

Looking a lot like the multi-faceted envelopes of viruses, carboxysomes are icosahedral, having about 20 triangle-shaped sides or facets. They contain copious amounts of Ribulose 1,5 Biphosphate Carboxylase Oxygenase (commonly called RuBisCo), an extremely abundant but slow enzyme required to fix carbon, inside their protein shells. The microcompartment also helps concentrate carbon dioxide and corral it near RuBisCo, while locking out oxygen, which otherwise tends to inhibit the chemical reactions involved in carbon-fixation.

Because they are so abundant, cyanobacteria play a major role in the earth's carbon cycle, the movement of carbon between the air, sea and land. "A significant fraction of global carbon fixation takes place in carboxysomes," said Kerfeld. Cyanobacteria, along with plants, impact climate change by lowering the amount of carbon from the atmosphere and depositing it in organic matter in the ocean and on land.

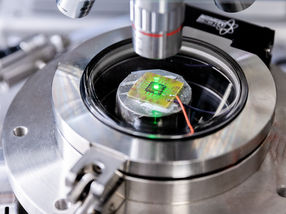

In order to track carboxysome assembly, the first author, Jeffrey Cameron, developed what Kerfeld called "an inducible system to turn on carboxysome biogenesis." He first developed mutant strains of a Synechococcus cyanobacterium that had its genes for building carboxysomes intentionally broken and then introduced the products of each of the knocked-out genes, which had been tagged with a fluorescent marker. He captured time-lapse digital images of the bacteria – a technique called time-lapse microscopy -- as they used the glowing building blocks and incorporated them into their new carboxysomes. The research team also painstakingly took high resolution still photographs using a transmission electron microscope of the intermediate stages of carboxysome construction. With these detailed images, they were able to provide a specific role for each product of each knocked-out gene, along with a timeline for how the bacteria built its carboxysomes. The team also suggested that other bacteria might build different types of microcompartments the same way carboxysomes are built, from the inside out.

It's the first time scientists have been able to watch bacterial organelles as they are built by living cells. Kerfeld noted that not only is the filming technique a major advance over previous methods, but that there are far-reaching implications for this work.

"The results provide clues to the organization of the enzymes encapsulated in the carboxysome and how this enhances CO2 fixation," said Kerfeld. Moreover, not only do the findings help researchers better understand how this previously mysterious compartment works, they can adapt what Kerfeld's team has learned about carboxysome architecture and apply it to designing synthetic nano-scale reactors. Understanding carbon-fixation in cyanobacteria contributes to our understanding of how this ubiquitous organism affects the global carbon cycle.