Genetic clues to the causes of primary biliary cirrhosis

Researchers find new risk regions associated with primary biliary cirrhosis

Researchers have newly identified three genetic regions associated with primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), the most common autoimmune liver disease, increasing the number of known regions associated with the disorder to 25.

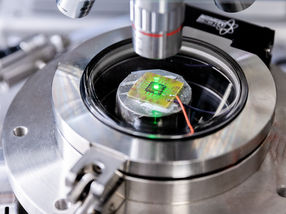

The team used a DNA microchip, called Immunochip, to survey more thoroughly regions of the genome known to underlie other autoimmune diseases to discover if they play a role also in PBC susceptibility. By combining the results from this survey with details of gene activity from a database called ENCODE, they were able to identify which cells types are most likely to play a role in PBC.

There is currently no cure for PBC, so treatment is focused on slowing down the progression of the disease and treating any symptoms or complications that may occur. The biological pathways underlying primary biliary cirrhosis are poorly understood, although autoimmunity, where the body attacks its own cells, is known to play a significant role.

"Previous genetic screens have identified 22 regions of the genome underlying PBC risk, and many of these are known to play a role in other autoimmune diseases, such as multiple sclerosis and type I diabetes," says Dr Carl Anderson, co-senior author from the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

"Using the Immunochip we were able to perform a much more thorough screen of the genomic regions previously associated with other autoimmune diseases. This resulted in us identifying a further three regions involved in PBC risk and identifying additional independent signals within some of those we already knew about."

The researchers found five genomic regions with multiple independent signals associated with the disorder, with one small region on chromosome 3 harbouring four independent association signals. These findings suggest that densely genotyping or sequencing known disease regions will be a powerful approach for identifying additional genetic risk variants and for further elucidating the role of rare genetic variation in complex disease risk.

"This study has allowed us to better understand the genetic risk profile of PBC and, by comparing our results with similar studies of other autoimmune diseases, we hope to further characterise the genetic relationship between this group of clinically diverse but biologically related disorders" says Dr Richard Sandford, co-senior author from the University of Cambridge "Over the next few years we will be extending our studies to search for genetic variants that affect disease course and treatment response. We hope that our studies will have a clinical impact, either directly through a more personalized approach to treatment or indirectly by furthering our understanding of the biological pathways underlying PBC leading to new treatments."

The most associated genetic variant within the newly implicated TYK2 gene was a low-frequency variant previously associated with multiple sclerosis (MS) that changes the coding sequence of the gene. Previous studies in MS have shown that individuals that carry a single copy of this variant have significantly reduced TYK2 activity, suggesting that modulation of TYK2 activity might represent a new therapeutic approach for the treatment of PBC.