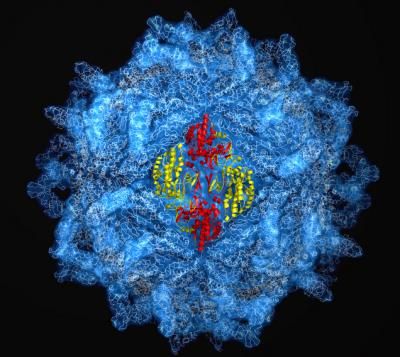

Image pinpoints all 5 million atoms in viral coat

Advertisement

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then rice University's precise new image of a virus' protective coat is seriously undervalued. More than three years in the making, the image contains some 5 million atoms - each in precisely the right place - and it could help scientists find better ways to both fight viral infections and design new gene therapies.

High-energy X-ray diffraction was used to pinpoint some 5 million atoms in the protective protein coat used by hundreds of viruses.

J. Pan & Y.J. Tao/Rice University

The image, which appears in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveals the structure of a type of protein coat shared by hundreds of known viruses containing double-stranded RNA genomes. The image was painstakingly created from hundreds of high-energy X-ray diffraction images and paints the clearest picture yet of the viruses' genome-encasing shell called a "capsid."

"When these viruses invade cells, the capsids get taken inside and never completely break apart," said lead researcher Jane Tao, assistant professor of biochemistry and cell biology at Rice.

Capsids come into play because viruses can reproduce themselves only by invading a host cell and hijacking its biochemical machinery. But when they invade, viruses need to seal off their genetic payload to prevent it from being destroyed by the cell's protective mechanisms. Though there are more than 5,000 known viruses, including whole families that are marked by wide variations in genetic payload and other characteristics, most of them use either a helical or a spherical capsid.

In their attempt to map precisely the spherical variety, Tao and lead author Junhua Pan, a postdoctoral fellow at Rice, first had to create a crystalline form of the capsid that could be X-rayed. They chose the oft-studied Penicillium stoloniferum virus F, or PsV-F, a virus that infects the fungus that makes penicillin. PsV-F uses the spherical capsid; although it does not infect humans, it is similar to a rotavirus and others that do.

Previous studies had shown that spherical capsids contain dozens of copies of the capsid protein, or CP, in an interlocking arrangement. The new research identified the sphere's basic building block, a four-piece arrangement of CP molecules called a tetramer, which could also be building blocks for other viruses' protein coats. By deciphering both the arrangement and the basic building block, the research team hopes to learn more about the capsid-forming process.

"Because many viruses use this type of capsid, understanding how it forms could lead to new approaches for antiviral therapies," Tao said. "It could also aid researchers who are trying to create designer viruses and other tools that can deliver therapeutic genes into cells."