Newly discovered gene may hold clues to evolution of human brain capacity

Scientists have discovered a gene that has undergone accelerated evolutionary change in humans and is active during a critical stage in brain development. Although researchers have yet to determine the precise function of the gene, the evidence suggests that it may play a role in the development of the cerebral cortex and may even help explain the dramatic expansion of this part of the brain during human evolution.

"At this point, we can only speculate about this gene's role in the evolution of the human brain, but it's exciting to find a new gene involved in brain development, and it's especially exciting for us because it validates our approach of letting evolution guide us and tell us what are the important parts of the human genome," said QB3 affiliate David Haussler, director of the Center for Biomolecular Science and Engineering (CBSE) at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) investigator.

The study, published by Nature was led by CBSE researchers Katherine Pollard and Sofie Salama, who worked with an international team of collaborators including neuroscientists in Belgium and France. Pollard, now an assistant professor of statistics at UC Davis, performed an extensive computational analysis, comparing the genomes of humans, chimpanzees, and other vertebrates to identify elements of the human genome that have undergone accelerated evolutionary changes.

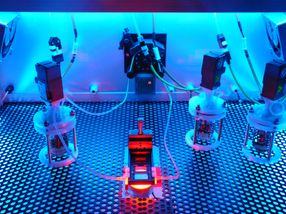

This computer-intensive bioinformatics approach produced a list of the most rapidly evolving regions of the human genome, and subsequent work focused on the top hit, a region called HAR1. Salama, a HHMI research biologist, led the "wet lab" investigations, using the laboratory techniques of molecular biology to characterize the gene, identify the tissues in which it is active, and begin the search to understand its function.

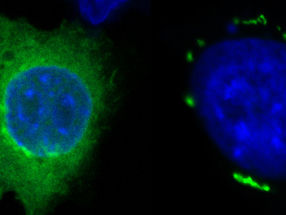

HAR1 is part of two overlapping genes. One of those genes, called HAR1F, is active in special nerve cells, called Cajal-Retzius neurons, that appear early in embryonic development and play a critical role in the formation of the layered structure of the human cerebral cortex. Cajal-Retzius neurons release a protein called reelin that guides the growth of neurons and the formation of connections among them. HAR1F is active at the same time as the reelin gene.

"We don't know what it does, and we don't know if it interacts with reelin. But the evidence is very suggestive that this gene is important in the development of the cerebral cortex, and that's exciting because the human cortex is three times as large as it was in our predecessors," Haussler said. "Something caused our brains to evolve to be much larger and have more functions than the brains of other mammals."

Pollard's analysis showed that HAR1 is essentially the same in all mammals except humans. There were only two differences between the chicken and chimp genomes in HAR1's sequence of 118 bases. This similarity means the DNA sequence remained unchanged over hundreds of millions of years of evolutionary history, an indication that it performs a biologically important function. But sometime after the human lineage diverged from its last common ancestor with chimpanzees 5 to 7 million years ago, HAR1 began to change rather dramatically.

"We found 18 differences between chimps and humans, which is an incredible amount of change to have happened in a few million years," Pollard said.

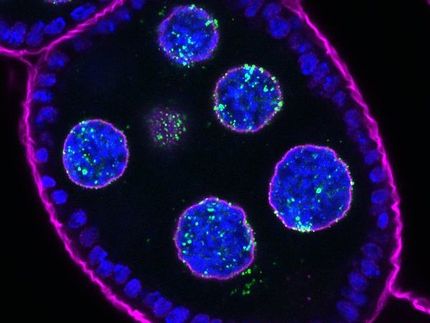

The researchers obtained preliminary evidence that HAR1F was active in the brain. Around that time, Pierre Vanderhaeghen, a neuroscientist at the University of Brussels, visited UCSC to give a seminar. Salama convinced him to include the new gene in a set of experiments he was planning, which would screen for active genes in a series of human embryonic brain sections.

HAR1F was first detected at seven and nine gestational weeks in the part of the embryonic brain that gives rise to the cerebral cortex. In subsequent experiments, collaborators in France looked at the corresponding gene in another primate, a macaque, and found a very similar pattern of expression in the developing macaque brain.

Unlike most known genes, HAR1F does not encode instructions for making a protein to carry out its function. Researchers are discovering a growing number of such "noncoding" genes, many of which produce functional RNA molecules. HAR1F appears to be a novel type of RNA gene, Salama said.

In the typical process by which genes are expressed or activated, the gene's DNA sequence is transcribed to produce a messenger RNA molecule, which then guides the synthesis of a specific protein. The encoded protein carries out the gene's function. Some genes, however, produce RNA molecules with special properties and biological effects.

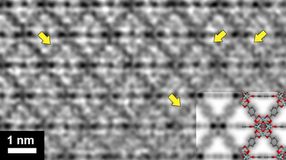

A common feature of such functional RNAs is that they tend to adopt a stable structure that enables them to interact with proteins and other molecules. These RNA structures involve the same kind of base pairing that holds together a double-stranded helix of DNA. UCSC researchers were able to demonstrate a stable structure for HAR1 RNA from humans and other vertebrates. Furthermore, 10 of the 18 changes in the human HAR1 sequence involved compensatory changes that preserved the base pairing in this structure.

"The HAR1 RNAs from both humans and chimps form stable structures, but there are significant differences," Salama said. "Our hypothesis is that these changes preserve the overall function of the molecule, but somehow alter its interactions with its binding partners. Those differences may have something to do with what makes our brain different from a chimp's."

Ongoing investigations may lead to more definitive findings about the function of HAR1, she said. Haussler noted that this project was one of the first to make use of the wet lab he established to explore and verify predictions generated from his group's computational genomic research.