Bringing artificial enzymes closer to nature

Scientists at the University of Basel, ETH Zurich in Basel, and NCCR Molecular Systems Engineering have developed an artificial metalloenzyme that catalyses a reaction inside of cells without equivalent in nature. This could be a prime example for creating new non-natural metabolic pathways inside living cells.

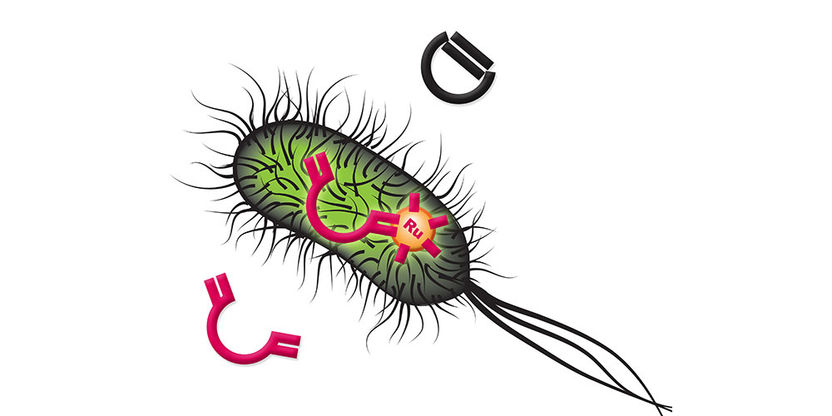

Representation of the new-to-nature olefin metathesis reaction in E. coli using a ruthenium-based artificial metalloenzyme to produce novel high added-value chemicals.

NCCR Molecular Systems Engineering

The artificial metalloenzyme, termed biot-Ru–SAV, was created using the biotin–streptavidin technology. This method relies on the high affinity of the protein streptavidin for the vitamin biotin, where compounds bound to biotin can be introduced into the protein to generate artificial enzymes. In this study the authors introduced an organometallic compound, with the metal ruthenium at its base. Organometallic compounds are molecules containing at least one bond between a metal and a carbon atom, and are often used as catalysts in industrial chemical reactions. However, organometallic catalysts perform poorly, if at all, in aqueous solutions or cellular-like environments, and need to be incorporated into protein scaffolds like streptavidin to overcome these limitations.

“The goal was to create an artificial metalloenzyme that can catalyse olefin metathesis, a reaction mechanism that is not present among natural enzymes,” says Thomas R Ward, Professor at the Department of Chemistry, University of Basel, and senior author of the study. The olefin metathesis reaction is a method for the formation and redistribution of carbon-carbon double bonds widely used in laboratory research and large-scale industrial productions of various chemical products. Biot-Ru–SAV catalyses a ring-closing metathesis to produce a fluorescent molecule for easy detection and quantification.

Periplasm as reaction compartment

However, the environment inside a living cell is far from ideal for the proper functioning of organometallic-based enzymes. “The main breakthrough was the idea to use the periplasm of Escherichia coli as a reaction compartment, whose environment is much better suited for an olefin metathesis catalyst,” says Markus Jeschek, a researcher from the team of co-supervising author Sven Panke at the Department of Biosystems Science and Engineering, ETH Zurich in Basel. The periplasm, the space between the inner cytoplasmic membrane and the bacterial outer membrane in gram-negative bacteria, contains low concentrations of metalloenzymes inhibitors, such as glutathione.

Having found ideal in vivo conditions, the authors went a step forward and decided to optimize biot-Ru–SAV by applying principles of directed evolution, a method that mimics the process of natural selection to evolve proteins with enhanced properties or activities. “We could then develop a simple and robust screening method that allowed us to test thousands of biot-Ru–SAV mutants and identify the most active variant,” Ward explains.

Not only could the authors markedly improve the catalytic properties of biot-Ru–SAV, but they could also show that organometallic-based enzymes can be engineered and optimized for different substrates, thus producing a variety of different chemical products. “The exciting thing about this is that artificial metalloenzymes like biot-Ru–SAV can be used to produce novel high added-value chemicals,” Ward says. “It has a lot of potential to combine both chemical and biological tools to ultimately utilize cells as molecular factories.”

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.