Rabbit virus improves bone marrow transplants, kills some cancer cells

Advertisement

University of Florida Health researchers have discovered that a rabbit virus can deliver a one-two punch, killing some kinds of cancer cells while eliminating a common and dangerous complication of bone marrow transplants.

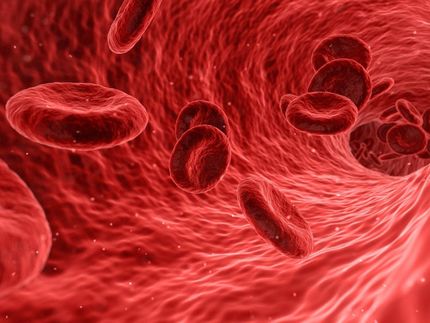

For patients with blood cancers such as leukemia and multiple myeloma, a bone marrow transplant can be both curative and perilous. It replenishes marrow lost to disease or chemotherapy but raises the risk that newly transplanted white blood cells will attack the recipient’s body.

Now researchers say the myxoma virus, found in rabbits, can do double duty, quelling the unwanted side effects of a bone marrow transplant and destroying cancer cells.

The virus could be especially helpful to patients who have recurring cancer but cannot find a suitable bone marrow donor, said Christopher R. Cogle, M.D., the study’s lead investigator and an associate professor in the UF College of Medicine’s division of hematology and oncology. Bone marrow transplants from partially matched donors carry about an 80 percent risk of graft-versus-host disease, and the myxoma treatment would address that, Cogle said.

The myxoma virus also could improve bone marrow transplant options among African-Americans and the elderly. Those patients are less likely to find fully matched bone marrow donors, which raises the risk of graft-versus-host disease, according to Cogle.

“Myxoma is one of the best strategies because it is effective but doesn’t affect normal stem cells,” he said.

During laboratory testing on human cells, the process worked this way: The myxoma virus is attached to a type of white blood cell known as a T-cell. The virus-laden white blood cells can then be delivered as part of a bone marrow transplant from a donor. That’s when the virus gets activated and goes to work. It blocks graft-versus-host disease, a complication of bone marrow transplants that can cause problems including skin rash, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, jaundice and muscle weakness. In severe cases, these complications can be fatal. The white blood cells then deliver the myxoma virus to cancer cells, which are killed off by the virus.

The findings were published in Blood. After successfully testing the process with human cells, researchers are now studying its effectiveness in a mouse model.

The dual action of the myxoma virus is particularly encouraging, said Grant McFadden, Ph.D., a professor in the UF College of Medicine department of molecular genetics and microbiology. It’s the first time that a virus has been shown to simultaneously prevent graft-versus-host disease and kill cancer cells in the laboratory, McFadden said.

The process is known to work on blood-related disorders such as multiple myeloma and acute myeloid leukemia but could someday have broader application for other kinds of cancer, he said. The myxoma virus originates among rabbits in Australia and parts of Europe and is benign to humans.