Researchers Identify “Naïve-Like” Human Stem Cells

In their search for the earliest possible stage of development of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) that still have the potential to develop into any types of body cells and tissue, researchers from the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine (MDC) Berlin-Buch, Germany, and the University of Bath, United Kingdom, have apparently been successful. Jichang Wang, Gangcai Xie, and Dr. Zsuzsanna Izsvák (MDC), together with Professor Laurence D. Hurst (University of Bath), report the discovery of a subtype of cells in culture dishes with hESCs and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) that resemble this very early, pluripotent or naïve state. They also discovered the mechanism that turns human ES cells into naïve-like human stem cells. While this has potential implications for medicine and for understanding early human development, an evolutionary enigma still remains unsolved.

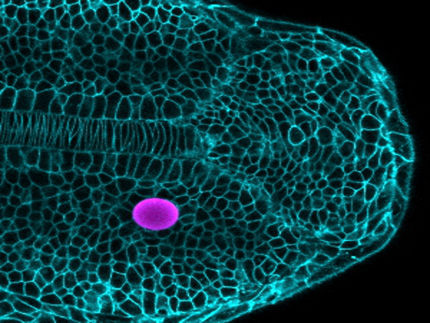

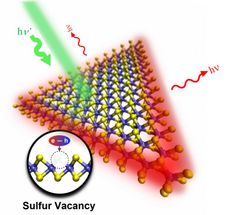

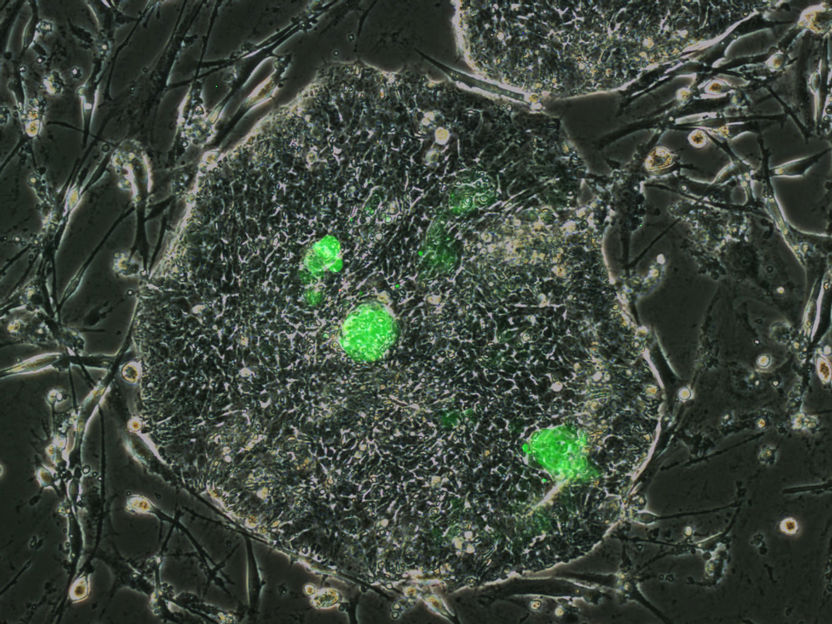

Newly discovered naïve-like human stem cells (green) in a culture dish with human embryonic stem cells.

Jichang Wang/ Copyright: MDC

Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) differ considerably from those of mice. Mouse naïve cultures resemble the inner cell mass which gives rise to the embryo, while none of the cultured hESC lines do. “Naïve” ESCs of mice are easy to maintain, but not human ESCs isolated from pre-implantation embryos. The hESC lines, researchers work with in their laboratories are considered to be less naïve, and have limited differentiation potential. Researchers hypothesize that they have partially lost their pluripotency. Why this is so remains unclear.

What properties characterize human naïve stem cells? Can they be identified and proliferated in the laboratory and retained in culture? Researchers in Europe, Asia and the USA are trying to find the answers to these questions in order to be able to use these cells for therapy in the future.

Evolution pointed the way

It was evolution that showed the researchers in Bath and Berlin the way to the successful approach. They pinpointed one particular class of ancient viruses called HERVH (human endogenous retrovirus H). HERVH integrated into our DNA millions of years ago, and although it does not function as a virus any longer, it is not silent.

HERVH-derived sequences appear at a very early stage in human embryos, that is, HERVH is highly expressed at just the right time and place in human embryos where one would expect to see naïve stem cells. This was also observed by Professor Kazutoshi Takahashi (Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan), almost at the same time when Dr. Izsvák and Professor Hurst made their discovery.

Dr. Izsvák and Professor Hurst succeeded in going one step further. They were able to identify the switch that regulates HERVH. In hESC cultures they identified a transcription factor – called LBP9 – as being central to the activity of HERVH in early embryos. Using a reporter system that made cells expressing HERVH via LBP9 glow green, the Berlin and Bath team found that they had purified human ESCs that showed all the hallmarks of naïve mouse stem cells.

This transcription factor was not previously known to be important to human stem cells. However, unknown to them at the time, the same transcription factor was shown by Austin Smith’s group (University of Cambridge, UK) to have a role in mouse naïve cells.

“Our human naïve-like cells look remarkably like the mouse ones, and are close to human inner cell mass (ICM),” said Jichang Wang (PhD student, MDC), first author of the Nature publication. “With our HERVH-based reporter system we can easily isolate naïve-like human ESCs from any human ESC culture. These cells grow like the mouse naïve stem cells and express many of the same genes such as NANOG, KLF4 and OCT4 that are associated with murine naïveté. When we knockdown LBP9 or HERVH, these cells no longer resemble naïve-like human stem cells,” he added.

To explore a potential role in stem cell-based therapeutics, the next task will be to keep these isolated human naïve-like stem cells in culture and proliferate them. HERVH would also be particularly useful in identifying optimal conditions for long-term culturing. As HERVH inhibits differentiation, its expression should be transient, otherwise it might be detrimental to normal embryo development. What factors keep this delicate process in balance is yet to be determined.

What puzzled the authors, however, was the fact that HERVH is only seen in primates (monkeys, apes, etc.). “As an evolutionary biologist, this is the aspect I find most curious,” commented Professor Hurst. “One would expect that a mechanism as important as pluripotency would be conserved in different species of mammals,” he pointed out. “The mystery deepens,” added Dr. Izsvák. “We found one gene, called ESRG, whose sequence is almost entirely derived from the virus HERVH. We do not know which role ESRG plays. However, when we knock it down, the human naïve-like stem cells lose their pluripotency. ESRG appears to be specific to humans and does not occur even in our closest relatives, the apes”.

The HERVH-driven human-specific regulatory network could at least partially explain why mouse and human ESCs are basically different. Therefore Dr. Izsvák suggests comparing human naïve-like stem cells with the inner human cell mass rather than with mouse naïve cells.

“How then did we evolve circuitry particular to us?” asks Professor Hurst. “It is a real enigma – why does evolution tinker with something that doesn’t obviously need tinkering with? We know that some proteins related to LBP9 are important in suppressing viruses – perhaps this is at the heart of the conundrum?”

Original publication

Jichang Wan et al.; Primate-specific endogenous retrovirus driven transcription defines naïve-like stem cells; Nature.

Ohnuki et. al. Dynamic regulation of human endogenous retroviruses mediates factor-induced reprogramming and differentiation potential, PNAS, 111, 12426-12431, August 26, 2014

Martello et. al. Identification of the missing pluripotency mediator downstream of leukaemia inhibitory factor EMBO J. 32, 2561-2574, 13 August 2013