Schizophrenia gene discovered

Working independently from different perspectives, geneticists from Finland and biochemists from Würzburg have researched the molecular mechanisms of schizophrenia and cognitive impairment. They have concluded that their results complement each other perfectly.

There is something peculiar, and macabrely so, that makes the population of Finland so interesting to geneticists: during the colonization of the country it is likely that there were several natural disasters that claimed many victims among the settlers and drastically reduced their number. This, combined with the fact that the individual settler tribes scarcely mingled with each other, has meant that in Finland today certain genetic defects occur much more frequently than in other European countries.

The risk rises in the north

This peculiarity is clear to see on a map. For example, the number of people with a neurodevelopmental disorder increases steadily the farther one moves from the south-west to the north-east of the country. Anyone who grows up in the far north-east, for instance, is approximately twice as likely to suffer from schizophrenia as a resident of the capital, Helsinki. The risk is lower in the region west of Helsinki. The same applies to other forms of cognitive disorders.

In the search for the genetic bases of schizophrenia and differing degrees of cognitive impairment, geneticists from Finland have now made a discovery: they were able to show that the loss of a gene on chromosome 22 roughly doubles the risk of developing one of these diseases. In their study of the population of north-eastern Finland they identified a defect in the so-called TOP3β gene that is responsible for the faulty development of the brain in those affected.

Two teams, one research subject

TOP3β: this, coincidentally, is the exact same gene, or protein, that scientists at the University of Würzburg’s Department of Biochemistry have long been researching. So, when they heard of the work by the Finnish geneticists led by Aarno Palotie and Nelson Freimer, Professor Utz Fischer, as the head of the department, and his colleagues Georg Stoll, Conny Brosi, and Bastian Linder immediately contacted Helsinki. As the ensuing discussions revealed, the projects of the two teams complement each other perfectly.

“The TOP3β protein is a topoisomerase that most biochemists do not expect to learn much more about and therefore dismiss out of boredom,” says Utz Fischer. It is well-known that topoisomerases are responsible for the spatial organization of DNA; until now they have not been associated with unknown exciting properties. Fischer and his team are looking at the enzyme for a different reason: “For some time now we have been exploring a complex composed of three proteins, the so-called TTF complex,” says Fischer.

Responsible for autism and schizophrenia

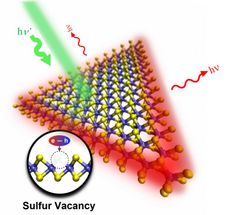

The central element of this complex is a protein with the name TDRD3. Attached to its ends are the TOP3β and FMRP proteins. This combination is quite something: a defect in the TOP3β gene is now known to increase the risk of schizophrenia, while it has been recognized for some time that FMRP is associated with Fragile X syndrome – one of the most common causes of an inherited cognitive disorder in humans. Sufferers have differing degrees of diminished intelligence; quite a few exhibit autistic traits or have epileptic seizures. “The TTF complex therefore possesses two components whose absence triggers symptoms that sit at opposite ends of the scale for autism spectrum disorders,” explains Georg Stoll. Defects in the TOP3β protein are linked to schizophrenia; damage to the FMRP protein increases the risk of autism.

What happens inside the cell

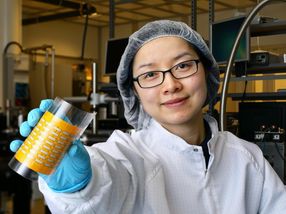

The Würzburg biochemists are interested in the TTF complex because they can use it to track how the information stored in DNA inside the cell nucleus is converted into proteins in the cytoplasm. “Our focus is on the fundamental question of how an mRNP is structured in the cell; this is a messenger RNA that is loaded with specific proteins,” explains Fischer. This structure is unique for every mRNP and determines its regulation upon transcription into proteins. Using the TTF complex as an example, the biochemistry team was able to uncover at least a few details of this process.

They found that the TDRD3 molecule binds to DNA in the cell nucleus via a protein-protein interaction and, in so doing, provides a link between the chromatin and the translation — in other words, the process by which genetic information is copied to mRNA molecules and the respective proteins are then synthesized. “This link was not known about before. It reveals one possible way in which the cell can specifically intervene in the fate of mRNA and how a dysregulation of mRNA can cause diseases,” says Fischer.

The impact on messenger RNA

TDRD3 also binds to mRNA – again via a protein-protein interaction. To achieve this, it docks onto the so-called exon junction complex, a molecule complex that is important in the processing, export, and quality control of RNA. The other components of the TTF complex, the TOP3β and FMRP proteins, then also come into play, causing the corresponding pathologies if they are faulty.

“We suspect that, depending on which protein is missing, mRNA is sometimes upregulated and sometimes downregulated,” says Georg Stoll. So far, however, this is only a hypothesis, which the scientists are now keen to investigate in further experiments, but, he points out, it would explain why one extreme of an autism spectrum disorder occurs in one given situation, while the other extreme occurs in another.

The biochemists believe that the basic result of their work is important: “We have been able to demonstrate that the topoisomerase TOP3β is active not only on DNA but also on RNA,” says Fischer. By so doing, the researchers have uncovered one way in which proteins use RNA to influence the reading of genetic information.