NSF grant boosts research on proteins that affect fertility

Infertility among men is a complex disorder that scientists are still trying to understand. Professor of Biology Diana Chu studies one factor that affects male fertility, and her research has attracted a new grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF).

In 2006, Chu identified new proteins found in sperm cells that that are critical for sperm to function properly. Since then she has been using a simple model organism, the tiny worm C. elegans, to find out more about how these sperm-specific proteins work.

"Sperm cells are unique," Chu said. "They have to be able to swim and deliver their genetic information when they fertilize an egg."

Chu studies proteins that package DNA so that it fits properly inside a sperm cell. These specialized proteins play a vital role in the creation of sperm and the successful delivery of DNA to a fertilized egg.

With her three-year NSF grant of $668,000, Chu and colleagues will explore how the chemical structure of sperm proteins affects how sperm DNA is packaged and interpreted. For these new biochemistry studies, she will collaborate with Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Raymond Esquerra and Geeta Narilkar from University of California, San Francisco.

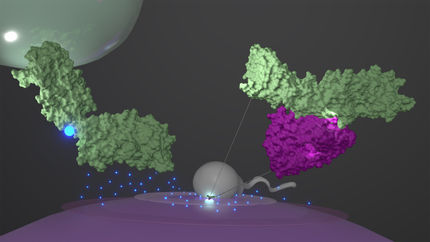

Inside sperm cells, long strands of DNA are wrapped around clusters of proteins in a formation that looks like beads on a necklace.

"The proteins that wrap DNA can fit together in different combinations, much like Lego blocks," Chu said. "The combinations of these proteins help the DNA to be read properly."

The interaction between the DNA and the proteins determines which genes are turned on or off in the sperm cell, influencing whether the sperm can function. The researchers want to find out what happens if one of the proteins is missing or altered.

"We'll remove one protein at a time and see whether the proteins can substitute for one another," Chu said. "If they can, it means that an animal whose sperm is missing one protein may still be able to reproduce. But if you're missing more than one protein you may be sterile."

This would explain what Chu and her students have observed in the lab. They created a mutant worm that was missing one sperm protein. The worm was able to reproduce but it produced 30-40 percent less offspring than typical worms.

"Sperm cells might have this safety mechanism that kicks in when one protein is missing, but that missing protein could still have implications later on, for example problems conceiving, miscarriage or birth defects."

Also funded by the NSF grant, Chu and her graduate students will continue their studies of tiny worms, observing what happens to the worms' reproduction when they have a different mix of proteins in their sperm.

"Our findings will help us understand more about fertility in humans and other animals," Chu said. "We hope they will also help researchers to answer broader scientific questions about how genes can be turned on and off through a subtle change in a single protein."

Chu's latest grant comes after her 2011 discovery of a group of enzymes that help worm sperm to develop and move. Her work has attracted several NSF grants, including the agency's prestigious CAREER award as well as funding for a state-of-the-art microscope at SF State.