A scanner for hereditary defects

Advertisement

Our genetic material is constantly exposed to damage, which the body’s own proteins normally repair. One of these proteins works like a scanner, continually scouring the genetic material for signs of damage. Researchers from the Institute of Veterinary Pharmacology and Toxicology at the University of Zurich see new possibilities in this damage recognition for improving cancer treatment in humans.

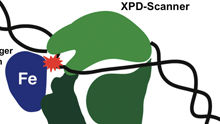

The XPD scanner (green) in close contact with a damaged point (red) on the DNA double helix. The damaged DNA strand lies in a deep pocket of the protein to enable a ferrous sensor (Fe) to come into contact with the damaged point, thereby halting the protein as it moves along the DNA.

UZH

Our DNA is constantly under attack from UV light, toxins and metabolic processes. Proteins and enzymes continually repair the damaged DNA. Unrecognized and therefore unrepaired damage to the genetic material, however, accelerates aging and causes cancer and genetic disorders. A team headed by veterinary pharmacologist and toxicologist Hanspeter Nägeli has now discovered that the protein XPD plays a key role in locating damaged DNA.

XPD protein as scanner

Genetic information is stored on approximately three billion base pairs of adenine/thymine or cytosine/guanine in the thread-like DNA double helix. The researchers reveal that the XPD protein works like a scanner that glides along the DNA double helix, scouring the bases for signs of damage. As soon as one of the protein’s ferrous sensors encounters damage as it moves along, it is stopped, thereby marking damaged spots in need of repair. Besides patching up DNA, XPD is also involved in cell division and gene expression, thus making it one of the most versatile cell proteins.

Basis for possible courses of therapy

While repairing the DNA protects healthy body tissue from damage to the genetic material, however, it diminishes the impact of many chemotherapeutic substances against cancer. “Damage recognition using XPD opens up new possibilities to stimulate or suppress DNA repair according to the requirements and target tissue,” explains Hanspeter Nägeli. The results could thus aid the development of new cancer treatments.