'Smart materials' that make proteins form crystals to boost research into new drugs

Scientists have developed a new method to make proteins form Crystals using 'smart materials' that remember the shape and characteristics of the molecule. The technique, reported in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, should assist research into new medicines by helping scientists work out the structure of drug targets.

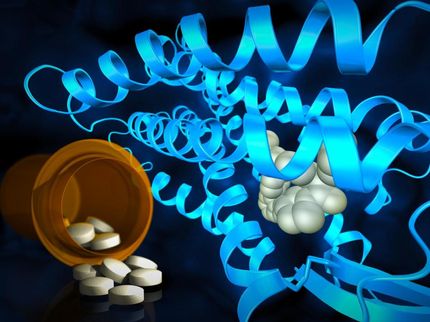

The process of developing a new drug normally works by identifying a protein that is involved in the disease, then designing a molecule that will interact with the protein to stimulate or block its function. In order to do this, scientists need to know the structure of the protein that they are targeting.

X-ray crystallography can be used to analyse the arrangement of atoms within a crystal of protein, but getting a protein to come out of solution and form a crystal is a major obstacle. The number of proteins identified as potential drug targets is increasing exponentially as scientists make progress in the fields of genomics and proteomics, but with current methods, scientists have successfully obtained useful crystals for less than 20 per cent of proteins that have been tried.

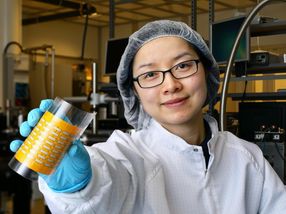

Now researchers at Imperial College London and the University of Surrey have developed a more effective method for making proteins crystallise using materials called 'molecularly imprinted polymers' (MIPs). MIPs are compounds made up of small units that bind together around the outside of a molecule. When the molecule is extracted, it leaves a cavity that retains its shape and has a strong affinity for the target molecule.

This property makes MIPs ideal nucleants – substances that bind protein molecules and make it easier for them to come together to form crystals. Many substances have been used as nucleants before, but none are designed specifically to attract a particular protein.

"Proteins are very comfortable in solution," said Professor Naomi Chayen, from the Department of Surgery and Cancer at Imperial College London, who led the research. "They need some convincing to come out and form a crystal.

"MIPs help this process by using the protein as a template for forming its own crystal. Once the first molecule or group of molecules is held in place, other molecules can arrange themselves around it and start to build a crystal."

In the study, Professor Chayen and her colleagues found that six different MIPs induced crystallisation of nine proteins, yielding crystals in conditions that do not give crystals otherwise. They also tested whether MIPs would be effective at producing crystals from a series of preliminary trials for three target proteins for which scientists have not previously been able to obtain crystals of sufficient quality. The presence of MIPs gave rise to crystals in eight to 10 per cent of such trials, yielding valuable crystals that would have been missed using other known nucleants.

"Rational drug design depends on knowing the structure of the protein you're trying to target, and getting good crystals is essential for studying the structure," Professor Chayen said. "With MIPs we can get better crystals than we can with other methods, and also improve the probability of getting crystals from new proteins. This is a really significant innovation that could have a major impact on research leading to the development of new drugs."

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.