Researchers shine light on how some melanoma tumors evade drug treatment

Advertisement

Researchers shine light on how some melanoma tumors evade drug treatment Findings pinpoint a critical gene involved in melanoma growth, provide a framework for discovering ways to tackle cancer drug resistance The past year has brought to light both the promise and the frustration of developing new drugs to treat melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer. Early clinical tests of a candidate drug aimed at a crucial cancer-causing gene revealed impressive results in patients whose cancers resisted all currently available treatments. Unfortunately, those effects proved short-lived, as the tumors invariably returned a few months later, able to withstand the same drug to which they first succumbed. Adding to the disappointment, the reasons behind these relapses were unclear.

Now, a research team led by scientists at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT has unearthed one of the key players behind such drug resistance. Published in Nature, the researchers pinpoint a novel cancer gene, called COT (also known as MAP3K8), and uncover the signals it uses to drive melanoma. The research underscores the gene as a new potential drug target, and also lays the foundation for a generalized approach to identify the molecular underpinnings of drug resistance in many forms of cancer.

"In melanoma as well as several other cancers, there is a critical need to understand resistance mechanisms, which will enable us to be smarter up front in designing drugs that can yield more lasting clinical responses," said senior author Levi Garraway, a medical oncologist and assistant professor at Dana-Farber and Harvard Medical School, and a senior associate member of the Broad Institute. "Our work provides an unbiased method for approaching this problem not only for melanoma, but for any tumor type."

More than half of all melanoma tumors carry changes (called "mutations") in a critical gene called B-RAF. These changes not only alter the cells' genetic makeup, but also render them dependent on certain growth signals. Recent tests of drugs that selectively exploit this dependency, known as RAF inhibitors, revealed that tumors are indeed susceptible to these inhibitors — at least initially. However, most tumors quickly evolve ways to resist the drug's effects.

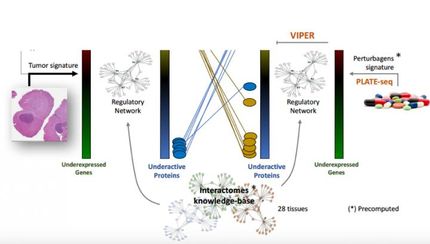

To explore the basis of this drug resistance, Garraway and his colleagues applied a systematic approach involving hundreds of different proteins called kinases. They chose this class of proteins because of its critical roles in both normal and cancerous cell growth. Garraway's team screened most of the known kinases in humans — roughly 600 in total — to pinpoint ones that enable drug-sensitive cells to become drug-resistant.

The approach was made possible by a resource created by scientists at the Broad Institute and the Center for Cancer Systems Biology at Dana-Farber, including Jesse Boehm, William Hahn, David Hill and Marc Vidal. The resource enables hundreds of proteins to be individually synthesized (or "expressed") in cells and studied in parallel.

From this work, the researchers identified several intriguing proteins, but one in particular stood out: a protein called COT (also known as MAP3K8). Remarkably, the function of this protein had not been previously implicated in human cancers. Despite the novelty of the result, it was not entirely surprising, since COT is known to trigger the same types of signals within cells as B-RAF. (These signals act together in a cascade known as the MAP kinase pathway.)

While their initial findings were noteworthy, Garraway and his co-workers sought additional proof of the role of COT in melanoma drug resistance. They analyzed human cancer cells, searching for ones that exhibit B-RAF mutations as well as elevated COT levels. The scientists successfully identified such "double positive" cells and further showed that the cells are indeed resistant to the effects of the RAF inhibitor.

"These were enticing results, but the gold standard for showing that something is truly relevant is to examine samples from melanoma patients," said Garraway.

Original publication: Johannessen CM et al., "COT/MAP3K8 drives resistance to RAF inhibition through MAP kinase pathway reactivation."; Nature 2010.