Scientists begin to unravel causes of mysterious skin disease

Advertisement

Scientists including researchers from the University of Florida have discovered additional evidence that generalized Vitiligo — a disease that typically causes patches of white skin on the face, neck and extremities that pop star Michael Jackson may have experienced — is associated with slight variations in genes that play a role in the body’s natural defenses.

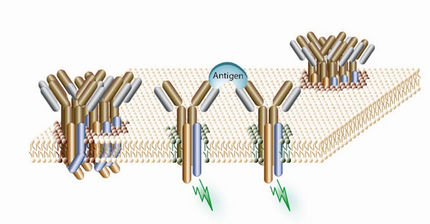

Writing in Nature Genetics, scientists describe how they found variations in 10 genes associated with the body’s immune response in people with vitiligo. Normally an immune response is a good thing, but with vitiligo, cells that guard the body apparently become too aggressive, killing pigment-producing cells called melanocytes that give color to skin.

The findings point toward the idea that there are multiple cellular pathways that may contribute to the onset and progression of vitiligo, which makes fully understanding the disease complicated, but it also gives scientists a variety of starting points to begin developing therapies.

“Generalized vitiligo is a complex disorder that involves not just genetics, not just the environment, but a combination of factors,” said Margaret “Peggy” Wallace, a professor of molecular genetics and microbiology and a member of the UF Genetics Institute and the Center for Epigenetics. “A number of different targets for therapies probably exist. As we do more research on the pathways underlying vitiligo, we can begin figuring out ways to interrupt them. This could present an opportunity to practice personalized medicine, in which therapies are tailored to people with different genetic susceptibilities.”

“Vitiligo may not get the attention it should because it is not life-threatening, but that’s not much consolation for people who have the disorder,” said Wayne McCormack, an associate professor of pathology, immunology and laboratory medicine and associate dean for graduate education with the College of Medicine. “It has a huge psychological effect on people. We live in a society that places value on personal appearance, and anyone who looks different, children in particular, can be made to feel very self-conscious and uncomfortable.”

Researchers, led by Dr. Richard Spritz, director of the Human Medical Genetics Program at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, identified genes that increase the risk for vitiligo by studying the complete sets of DNA, known as genomes, of more than 1,500 people who have the disease compared with the genomes of similar people without the disease.

The latest findings point in part to the Fox family of genes, which are known to regulate gene expression and function in T cells and other molecular infection fighters in the body. In May, the research team published findings in The New England Journal of Medicine implicating several other genes involved in other autoimmune diseases in which immune cells mistake normal parts of the body for invaders, as well as a gene that may uniquely target the mistaken immune response to melanocytes in the skin.