How cells generate heat by burning calories

“People who train their brown fat through regular cold exposure are thinner and less prone to developing diabetes and cardiovascular diseases”

Advertisement

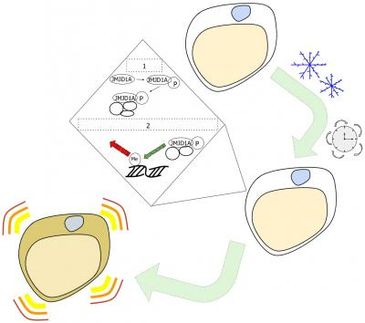

Special fat cells known as brown adipocytes help maintaining body temperature by converting calory-rich nutrients into heat. This protects from gaining excess weight and metabolic disorders. An international team of researchers led by Professor Alexander Bartelt from the Institute for Cardiovascular Prevention (IPEK) has deciphered a new mechanism that increases respiration and metabolic activity of brown fat cells. The researchers hope that this discovery will lead to novel approaches utilizing brown fat against metabolic diseases. Their results were recently published in The EMBO Journal.

Brown adipocytes attack fat stores

The activation of fat-burning cells makes people lose weight. When it is cold, brown adipocytes extract their fuel from storage fat, as thermogenesis requires a lot of calories. “People who train their brown fat through regular cold exposure are thinner and less prone to developing diabetes and cardiovascular diseases,” says Bartelt. Brown fat cells are particularly rich in mitochondria, the power plants where cellular respiration takes place. However, science does not yet sufficiently understand how brown fat cells boost metabolism such that new therapies could be developed.

Cold stimulates thermogenesis

The molecular trick of brown fat cells is uncoupling protein-1, which facilitates that heat is generated instead of ATP, the conventional product of cellular respiration. “The high metabolic activity of brown fat cells must also influence the production of ATP,” says Bartelt, “and we hypothesized that this process would be regulated by cold.” Together with Brazilian colleagues from São Paulo, the researchers identified “inhibitory factor 1,” which ensures that ATP production is maintained instead of thermogenesis. When temperature goes down, the levels of inhibitory factor-1 fall and thermogenesis can take place. When artificially increased, inhibitory factor 1 disrupts the activation of brown fat in the cold.

These findings were obtained in isolated mitochondria, cultivated cells, and an animal model. “While we have found an important piece of the puzzle for understanding thermogenesis, therapeutic applications are still a long way off,” explains Dr. Henver Brunetta, who conducted the study. According to the authors, most people use their brown fat too little and it becomes dormant. The new study results indicate that there are molecular switches that allow mitochondria of brown fat cells to work better. Bartelt and his colleagues plan to build on this discovery. “Ideally, we’ll find new ways, based on our data, to also restore the fitness of mitochondria in white fat cells, as most people have plenty if not too many of them,” concludes Bartelt.