Histology in 3D

New staining method enables Nano-CT imaging of tissue samples

To date, examining patient tissue samples has meant cutting them into thin slices for histological analysis. This might now be set to change – thanks to a new staining method devised by an interdisciplinary team from the Technical University of Munich (TUM). This allows specialists to investigate three-dimensional tissue samples using the Nano-CT system also recently developed at TUM.

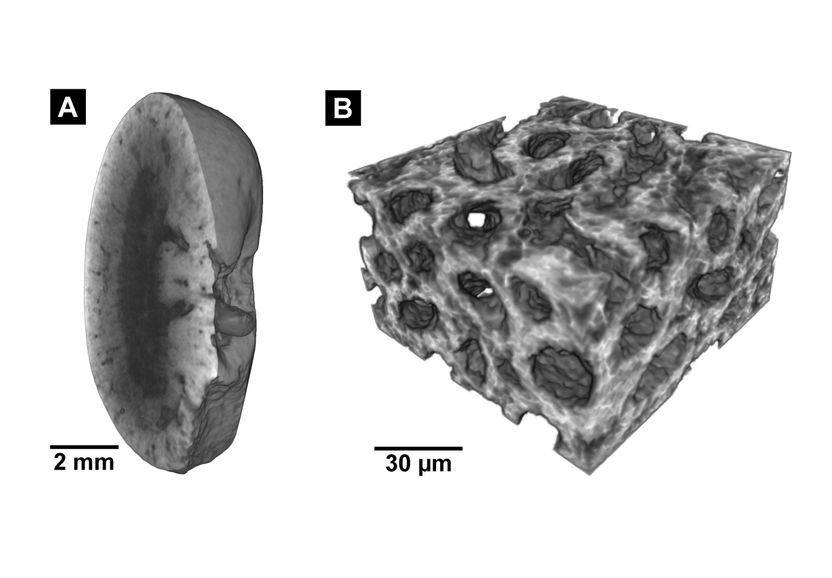

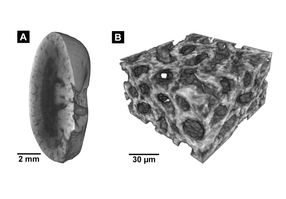

These images were created using the new staining method: left: Micro-CT image of a mouse kidney, right: Nano-CT image of the same tissue.

Müller, Pfeiffer / TUM / reproduced with permission from PNAS)

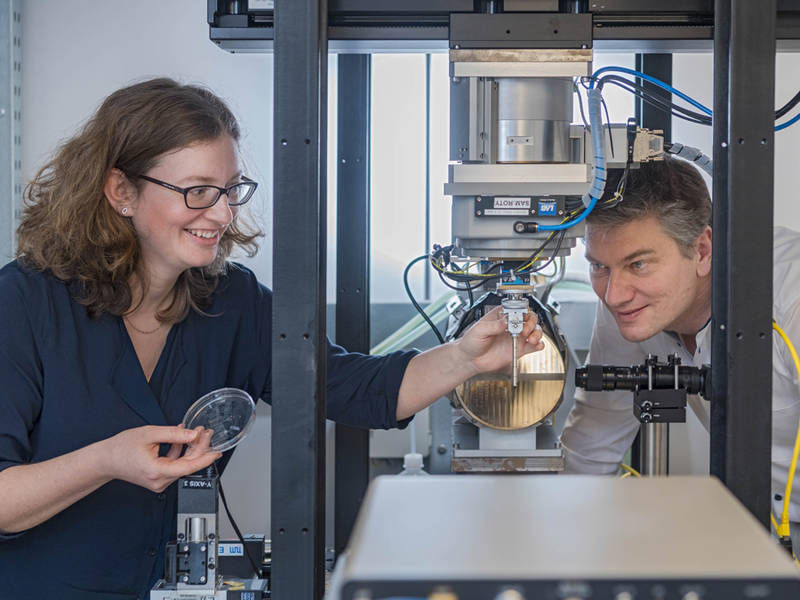

Chemist Dr. Madleen Busse has started from a standard staining procedure to develop a staining method suited for CT.

Heddergott / TUM

Tissue sectioning is a routine procedure in hospitals, for instance to investigate tumors. As the name implies, it entails cutting samples of body tissue into thin slices, then staining them and examining them under a microscope. Medical professionals have long dreamt of the possibility of examining the entire, three-dimensional tissue sample and not just the individual slices. The most obvious way forward here lies in computed tomography (CT) scanning – also a standard method used in everyday clinical workflows.

Previous limitations in resolution and contrast

Thus far, there have been two major hurdles to the realization of this goal. Firstly, the resolution of conventional CT scanners is too low. Today’s Micro- and Nano-CT systems are rarely suitable for use in frontline medicine. Some do not offer sufficiently high resolution, while others rely on radiation from large particle accelerators.

Secondly, soft tissue is notoriously difficult to examine using CT equipment. Samples have to be stained to render them visible in the first place. Stains for CT scanning are sometimes highly toxic, and they are also extremely time-consuming to apply. At times they modify the tissue to such an extent that further analysis is then impossible.

Successful collaboration between physics, chemistry and medicine

Now, however, scientists at TUM’s Munich School of BioEngineering (MSB) have solved both problems. In November 2017, Prof. Franz Pfeiffer and his team unveiled a Nano-CT system that delivers resolutions of up to 100 nanometers and is suitable for use in typical laboratory settings. In the current issue of the scientific journal PNAS, the cross-disciplinary research team from physics, chemistry and medicine also presents a staining method for histological examination with Nano-CT.

Using a mouse kidney, the scientists have successfully demonstrated that Nano-CT is able to generate 3D images that match the information granularity of tissue sections. At the core of the staining method lies eosin, a standard dye used in tissue sampling that was previously considered unsuitable for CT.

“Our approach included developing a special pre-treatment so that we can use eosin anyway,” outlines chemist Dr. Madleen Busse. The staining method is so time-efficient that it is also suited to everyday clinical workflows. “Another important benefit is that there are no problems using established methods to examine the tissue sample following the scan,” adds Busse.

Enhancement rather than replacement

In the next step, the researchers are looking to examine human tissue samples. However, CT histology is not set to replace conventional methods any time soon. For the moment, at least, the team views the new procedure as supplementary – for instance giving doctors additional insights into the three-dimensional distribution of cells and nuclei. Franz Pfeiffer also sees new opportunities here for basic medical research: “Alongside diagnostic applications, the non-destructive 3D examination enabled by Nano-CT could deliver new insights into the microscopic origins of widespread diseases such as cancer.”