Caltech scientists develop DNA origami nanoscale breadboards for carbon nanotube circuits

In work that someday may lead to the development of novel types of nanoscale electronic devices, an interdisciplinary team of researchers at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) has combined DNA's talent for self-assembly with the remarkable electronic properties of carbon nanotubes, thereby suggesting a solution to the long-standing problem of organizing carbon nanotubes into nanoscale electronic circuits. A paper about the work appeared in Nature nanotechnology .

Both the initial idea for the project and its eventual execution came from three students: Hareem T. Maune, a graduate student studying carbon nanotube physics in the laboratory of Marc Bockrath (then Caltech assistant professor of applied physics, now at the University of California, Riverside); Si-ping Han, a theorist in materials science who is investigating the interactions between carbon nanotubes and DNA in the Caltech laboratory of William A. Goddard III, Charles and Mary Ferkel Professor of Chemistry, Materials Science, and Applied Physics; and Robert D. Barish, an undergraduate majoring in computer science who was working on complex DNA self-assembly in the lab of Erik Winfree, associate professor of computer science, computation and neural systems, and bioengineering at Caltech, and one of four faculty members supervising the project.

The project began in 2005, shortly after Paul W. K. Rothemund invented his DNA origami technique. At the time, Rothemund was a postdoctoral scholar in Winfree's laboratory; today, he is a senior research associate in bioengineering, computer science, and computation and neural systems. Rothemund's work gave Maune, Han, and Barish the idea to use DNA origami to build carbon nanotube circuits.

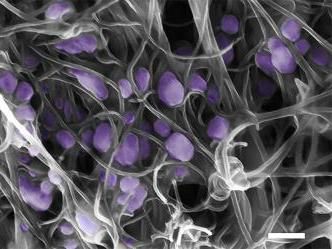

DNA origami is a type of self-assembled structure made from DNA that can be programmed to form nearly limitless shapes and patterns, such as smiley faces or maps of the Western Hemisphere or even electrical diagrams. Exploiting the sequence-recognition properties of DNA base paring, DNA origami are created from a long single strand of viral DNA and a mixture of different short synthetic DNA strands that bind to and "staple" the viral DNA into the desired shape, typically about 100 nm on a side.

"After hearing Paul's talk, Hareem got excited about the idea of putting nanotubes on origami," Winfree recalls. "Meanwhile, Rob had been talking to his friend Si-Ping, and they independently had become excited about the same idea."

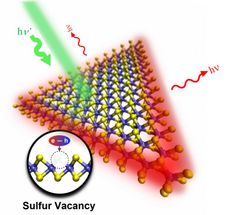

Underlying the students' excitement was the hope that DNA origami could be used as 100 nm by 100 nm molecular breadboards — construction bases for prototyping electronic circuits — on which researchers could build sophisticated devices simply by designing the sequences in the origami so that specific nanotubes would attach in preassigned positions.

Bringing the students' ideas to fruition wasn't easy. "Carbon nanotube chemistry is notoriously difficult and messy — the things are entirely carbon, after all, so it's extremely difficult to make a reaction happen at one chosen carbon atom and not at all the others," Winfree explains.

"This difficulty with chemically grabbing a nanotube at a well-defined 'handle' is the essence of the problem when you're trying to place nanotubes where you want them so you can build complex devices and circuits," he says.

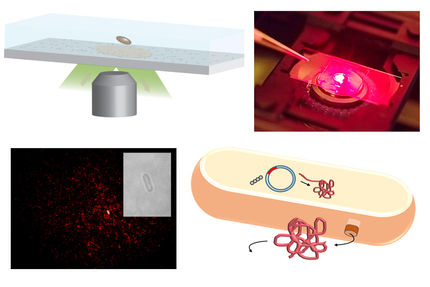

The scientists' ingenious solution was to exploit the stickiness of single-stranded DNA to create those missing handles. It's this stickiness that unites the two strands that make up a DNA helix, through the pairing of DNA's nucleotide bases (A, T, C, and G) with those that have complementary sequences (A with T, C with G). The scientists created two batches of carbon nanotubes labeled by DNA with different sequences, which they called "red" and "blue."

"Metaphorically, we dipped one batch of nanotubes in red DNA paint, and dipped another batch of nanotubes in blue DNA paint," Winfree says. Remarkably, this DNA paint acts like color-specific Velcro.

"These DNA molecules served as handles because a pair of single-stranded DNA molecules with complementary sequences will wrap around each other to form a double helix. Thus," he says, "red can bind strongly to anti-red, and blue with anti-blue."

"Consequently," he adds, "if we draw a stripe of anti-red DNA on a surface, and pour the red-coated nanotubes over it, the nanotubes will stick on the line. But the blue-coated nanotubes won't stick, because they only stick to an anti-blue line."

To make nanometer-scale electronic circuits out of carbon nanotubes requires the ability to draw nanometer-scale stripes of DNA. Previously, this would have been an impossible task. Rothemund's invention of DNA origami, however, made it possible.

"A standard DNA origami is a rectangle about 100 nm in size, with over 200 'pixel' positions where arbitrary DNA strands can be attached," Winfree says. To integrate the carbon nanotubes into this system, the scientists colored some of those pixels anti-red, and others anti-blue, effectively marking the positions where they wanted the color-matched nanotubes to stick. They then designed the origami so that the red-labeled nanotubes would cross perpendicular to the blue nanotubes, making what is known as a field-effect transistor (FET), one of the most basic devices for building semiconductor circuits.

Although their process is conceptually simple, the researchers had to work out many kinks, such as separating the bundles of carbon nanotubes into individual molecules and attaching the single-stranded DNA; finding the right protection for these DNA strands so they remained able to recognize their partners on the origami; and finding the right chemical conditions for self-assembly.

After about a year, the team had successfully placed crossed nanotubes on the origami; they were able to see the crossing via atomic force microscopy. These systems were removed from solution and placed on a surface, after which leads were attached to measure the device's electrical properties. When the team's simple device was wired up to electrodes, it indeed behaved like a field-effect transistor. The "field effect" is useful because "the two components of the transistor, the channel and the gate, don't actually have to touch for there to be a switching effect," Rothemund explains. "One carbon nanotube can switch the conductivity of the other due only to the electric field that forms when a voltage is applied to it."

At this point, the researchers were confident that they had created a method that could construct a device from a mixture of nanotubes and origami.