Cell-free protein production

New way to produce critical proteins for medicine and industry sidesteps use of live cells

Advertisement

A new method developed by Cornell biological engineers offers an efficient way to make proteins for use in medicine or industry without the use of live cells. The proteins made in this way include many that cannot be produced by current biotechnology.

Current methods employ vats of genetically modified bacteria or mammalian cells that churn out proteins for such pharmaceuticals as insulin or human growth hormone. But there are many proteins that bacteria or cells cannot tolerate. Anti-microbials, for example, are meant to kill bacteria and so would kill the host. And many key proteins that are important in regulating the normal life of a cell would also kill the host if overproduced inside a cell.

Researchers have tried mixing DNA that codes for the desired protein with the amino acids from which proteins are made along with ribosomes and other helper chemicals in a test tube. Cornell's faster, more efficient process weaves the coding DNA into an artificial gel made of synthetic DNA. The process is described in the journal Nature Materials by Dan Luo, Cornell associate professor of biological and environmental engineering, and colleagues.

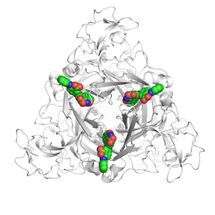

Luo's group has pioneered the use of synthetic DNA as a self-assembling construction material. Strands of DNA that are designed to be complementary over a small part of their length can join together into various shapes. In this application they form crosses, which in turn link at their ends to form a 3-D matrix. This makes a hydrogel, a spongy material that absorbs water without dissolving in the water.

To make a protein-producing gel, which Luo calls a P-gel, the synthetic DNA is also made to include sequences that join to the ends of plasmids - strands of DNA that code for the desired protein. A mix of X-shaped and plasmid DNA then assembles into a gel with genes coding for the desired protein integrated throughout. To increase the surface area for reaction, tiny drops of the P-gel are molded into pads about 1 millimeter square by 20 microns thick. Several hundred pads are then placed in a solution of amino acids and protein-making machinery extracted from living cells.

The result, Luo reports, is to produce proteins up to 300 times more efficiently than when the same reactions are carried out with DNA floating freely in the same solution. The system has so far been tested with 16 proteins, including several that are toxic or would otherwise be impossible to make in living cells.

Workers in Luo's lab have spent nearly a year trying variations of the process to find out why it works so well and suggest several reasons: Genes locked into the hydrogel are protected from damage they might suffer when floating free; much more DNA can be packed into the P-gels than can be dissolved in a given amount of solution; and because the genes are close together, enzymes taking part in the transcription process remain close by and can perform more quickly.