New images of marine microbe illuminate carbon and nitrogen fixation

Advertisement

Trichodesmium is unusual among marine microbes because it both "breathes" carbon dioxide like plants, while also taking nitrogen gas from the air and "fixing" it into a fertilizer of the seas. How Tricho does both these things has long puzzled researchers, since the two processes don't work well together: fixing carbon dioxide creates oxygen, and oxygen inhibits the enzyme that makes fixing nitrogen possible. It would be as if breathing made it hard to grow.

"Everyone has been trying to figure out how they do it," said USC microbiologist Juliette Finzi-Hart. "The more we can understand how it functions, the better we can model it, and the better we can understand its role in the context of the global carbon and nitrogen cycles."

In a new study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Finzi-Hart and colleagues offer new evidence that Tricho spends part of the day focusing on carbon and the other part on nitrogen. Using advanced imaging technology rarely used in the marine sciences, the study lends support to the theory that Tricho manages to fix both by separating the processes in time. The stunning pictures also revealed specific hotspots where fixed nitrogen is temporarily stored, and offers strong evidence that Tricho fixes both nitrogen and carbon in the same cell.

As a cyanobacterium, Tricho uses sunlight to fix carbon dioxide and turn it into food, using a process like photosynthesis. In addition, it's a major nitrogen fixer, making it a "fertilizer for the open ocean." Just like fertilizer in a field, Tricho's fixed nitrogen makes the seas thrive, and along with other nitrogen fixers, they in effect control the health of entire ecosystems. Theories about how Tricho fixes both carbon and nitrogen have largely fallen into two camps.

"Time" advocates believe that Tricho, like some other microorganisms, separates carbon and nitrogen fixation by time. At peak sun, carbon fixation gets inhibited, less oxygen is formed, and a window opens for nitrogen fixation to ramp up.

"Space" advocates, on the other hand, believe that Tricho physically separates the carbon and nitrogen fixation processes in a kind of "division of labor."

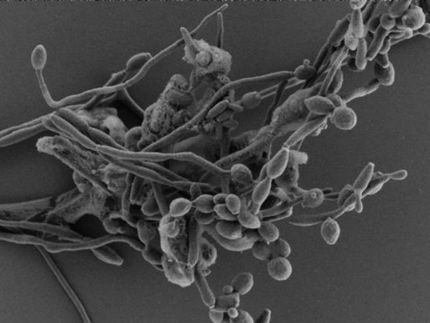

Tricho is a single-cell organism that lives in colonies. Each cell is stacked on top of one another in long filaments called trichomes, and these trichomes clump together.

"They look like eyelashes," Finzi-Hart said. "When you collect a sample, you get a big bucket and a big scoop, and you have a table of 15 scientists literally picking out Tricho by hand."

In at least one other type of cyanobacteria, the cells of a filament form groups: some cells fix carbon, while others take care of the nitrogen.

"For a lot of organisms, they either fix carbon during the day and nitrogen at night, or if they're a long chain organism, they'll have certain cells that are partitioned off," Finzi-Hart explained.

The time-space debate is tricky in the case of Trichodesmium, however. "With Tricho, it looks like one individual cell can do both."

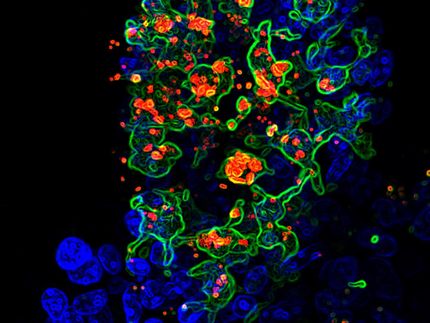

Finzi-Hart and colleagues turned to NanoSIMS, a specialized imaging technology used mainly in the planetary and medical sciences. USC's Doug Capone and Ken Nealson were among the first to adopt the technique in marine microbiology, working closely with Jennifer Pett-Ridge and Peter Weber of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. NanoSIMS allows scientists to see stable isotopic forms of carbon and nitrogen as they are fixed. These isotopes light up like honing beacons in the images produced by the spectrometer.

In this study, Finzi-Hart and colleagues examined the insides of Tricho cells to watch the tagged carbon and nitrogen at different points over a 24-hour period. The resulting pictures showed both where the nitrogen ended up within a cell and also how that distribution, and the quantity, changed over time. In short, the technique offered a new way to look at the debate from both the time and space points of view. The study found strong evidence in support of the temporal separation thesis. Over the 24-hour period, the images clearly demonstrated that just after carbon fixation peaked, nitrogen fixation picked up.

When it came to nitrogen, the images were startling: one could see the fixed tagged nitrogen slowly enter the cell, and after a few hours pool into concentration "hotspots," then see these hotspots subside into a more uniform distribution. (Comparing these images to others suggested that the hotspots were storage organelles called cyanophycin.)

"Basically they were taking the nitrogen, fixing it, storing it, using it, and then starting the whole process again the next day," Finzi-Hart said.

In terms of the spatial segregation theory, things were more complicated. At first, the researchers thought they uncovered clear evidence that there was no division of labor, because carbon and nitrogen tags were uniformly present across a broad sample of cells. In other words, there was no cluster of cells that fixed only nitrogen and other clusters that fixed only carbon, as was predicted by the spatial segregation theory.

However, previous studies have shown that after fixing nitrogen, Tricho cells are able to redistribute the nitrogen in as little as 90 seconds. Since the earliest NanoSIMS images were taken 15 minutes after introducing the isotopes, it is possible that there was spatial segregation that just didn't get captured. Still, the evidence is pointing towards Tricho having the ability to fix both carbon and nitrogen without divvying up the work. "If there is a division of labor, it's transient," she said.