Team Led by Scripps Research Scientists Uncovers New Way to Limit Damaging Production of Nitric Oxide

Results Could Lead to New Treatments for Conditions From Inflammation to Cancer

Excess nitric oxide production by one enzyme has been tied to human illnesses ranging from inflammation to cancer, but adequate treatments for the problem have been elusive. Now, work led by scientists at The Scripps Research Institute has revealed a new method for chemically targeting this single enzyme to block troubling nitric oxide production, without limiting its beneficial production by other closely related enzymes. This technique provides a general solution that should enable development of new drugs to treat medical problems tied to nitric oxide overproduction, such as arthritis, and may also aid the discovery of treatments for other conditions such as HIV/AIDS. The study was released as an Advance Online Publication by the journal Nature chemical biology.

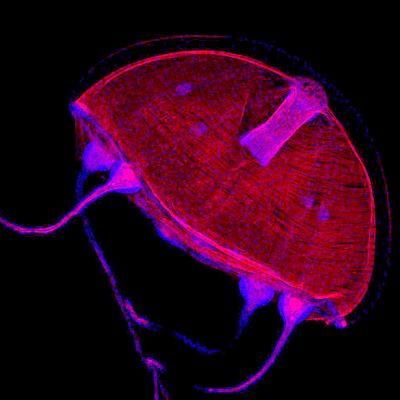

Three different enzymes from the same family produce the biologically critical signaling molecule nitric oxide (NO) in the human body by breaking off an atom of nitrogen from the amino acid L-arginine and combining it with oxygen. These enzyme relatives are known as isozymes because they all perform the same basic role chemically, but the NO they produce can have very different biological effects, depending on how much, when, and where it is released.

While NO overproduction by one enzyme, known as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), can cause rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, stroke, neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, and other conditions, too little NO production by the related isozymes is linked to everything from hypertension to impotence. In fact, the popular impotence drug Viagra works by inducing increased NO production.

Over a span of a decade, Getzoff and her colleagues have been studying the question of how to limit iNOS NO production, without causing other problems. "Ideally you want to turn that process off without inhibiting the other two related isozymes," says Professor Elizabeth Getzoff of Scripps Research, who led the study with Research Associate Elsa Garcin. Inhibitors have been developed to accomplish this, but to date have not been very successful as drugs, because of major drawbacks such as high toxicity or poor specificity.

One of the main challenges in developing iNOS inhibitors is that drugs are typically designed to bind in an enzyme's active site, where they can block the enzyme's functions of binding to other molecules and acting on them. But the active sites for all three of the NO producers are chemically identical, meaning that a drug targeting the active site for iNOS would also impede the beneficial activity of the other enzymes.

In hopes of finding a way around this problem, the Getzoff team studied iNOS inhibitors previously identified through research by collaborator AstraZeneca. Even though these inhibitors had not yet proven adequate as drug treatments, they could still provide important clues about how to develop better inhibitors.

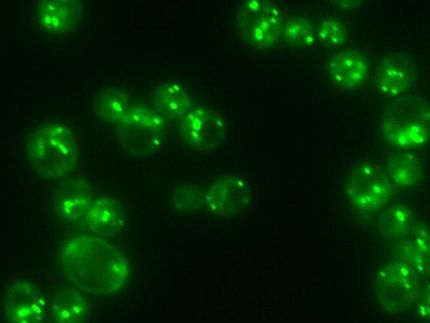

The team used x-ray crystallography, which produces atomic-level maps of molecules, to examine what was happening when these inhibitors bound to iNOS. Their goal was to solve the mystery of what allowed certain inhibitors to bind more effectively to iNOS than the other isozymes. "We tried to look at the nitty gritty level where atoms bind," says Getzoff, and the effort led to a surprising revelation.

Through the x-ray crystallography experiments, the Getzoff team discovered that for some inhibitors, effective binding to iNOS depended on interactions farther away from the active site than was suspected. The x-ray maps revealed that while the inhibitors first attach to iNOS molecules at the active site, they are only loosely anchored. But this initial interaction sets off a cascade of transformations in the iNOS molecule that ultimately exposes a binding pocket unique to iNOS.

The inhibitors only bind strongly enough to iNOS to block NO production when a tail on these molecules whips around to fit into this exposed iNOS pocket. These inhibitors might make the same loose initial connection with the other two isozymes, but do not block their NO production, because the tail can't bind tightly without the complementary pocket.

Based on this research, the team believes that new iNOS inhibitors can now be identified. The goal would be to design new molecules that perform the same way as existing inhibitors, an attachment pattern the team refers to as anchored plasticity, but without the side effects that have plagued the other inhibitors.