By growing 3D tumors, CU researcher develops realistic cancer growth models

Advertisement

Scientists can only develop new cancer drugs or search for cures by testing their theories on the real thing. Traditionally, they've done so by culturing cancer cells on petri dishes or plastic slides. But those cancer cells do not behave the way they do in the body. They only partially re-create the aggressive behavior of tumors in real patients.

That is the problem that drives Claudia Fischbach-Teschl, Cornell assistant professor of biomedical engineering, whose lab creates realistic experimental tumor models, which may then lead to better drug therapies or even a cure. "We allow cells to grow in a 3D manner and to reorganize into tissue that better mimics their behavior and composition in the body," Fischbach-Teschl explained.

On temperature-, carbon dioxide- and humidity-controlled shelves in her lab at the Baker Institute for Animal Health, Fischbach-Teschl handles vials of pinkish, sugar-based liquids that contain what look like tiny, white floating globules. But when slid under a microscope, the beads can be seen to serve as holders, or scaffolds, of hundreds of cancer cells.

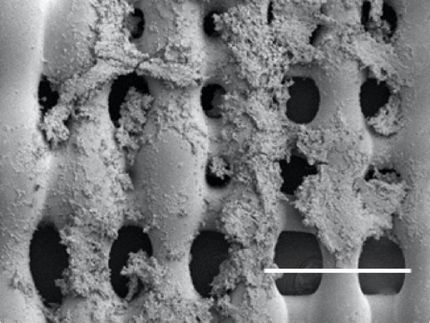

These 3D scaffolds, synthetically or naturally derived polymeric substances, act as harnesses for tumors cells as they grow, allowing the tumors to develop more closely to how they grow in the body than when maintained on flat plastic surfaces.

Fischbach-Teschl's work also involves trying to figure out why cancer cells are so able to adapt to the body's environment, why they are able to survive, and what biological secretions or proteins allow these cells to reproduce at a destructive rate.

Earlier this year in research published in Nature Methods, Fischbach-Teschl and colleagues, including David J. Mooney at Harvard University, showed that tumors grown in a 3D manner are resistant to cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy. They found the tumor models' behavior more aggressive than those grown on traditional glass slides.

Furthermore, an earlier generation of 3D tumor models, grown in what is known as a Matrigel culture, is limited in its ability to develop such characteristics. Instead, the Cornell scientists grew tumors in synthetic, porous scaffolds made of a lab-created polymer called poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLG). The PLG scaffolds, which look like tiny, white, flat sponges, allow the tumors to grow much more aggressively than in the Matrigel.

By then injecting the tumors into mice for in-vivo analysis, the researchers discovered that the tumors pregrown in the PLG scaffolds developed into bigger and more aggressive tumors. They also were able to analyze distinct biological functions of the cells, such as the presence of secretions that might point to the cancer cells' ability to survive.

The purpose of Fischbach-Teschl's research is to gain a fundamental understanding of cancer cell behavior that can be used to develop more effective anti-cancer drug therapy.