Two rapidly evolving genes offer Cornell geneticists clues to why hybrids are sterile or do not survive

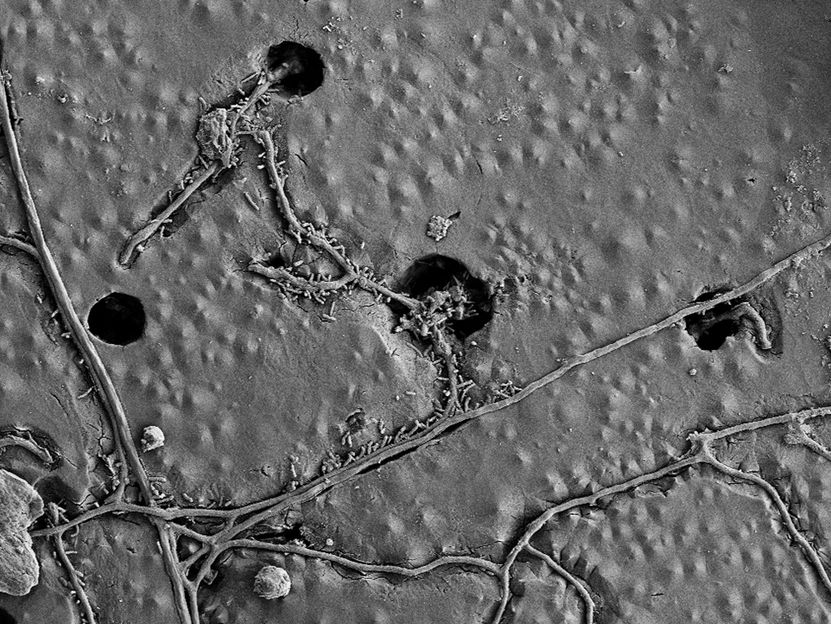

While hybrids may offer interesting and beneficial traits, they are usually sterile or unable to survive. For example, a mule, the result of the mating of a horse and a donkey, is sterile. Now, Cornell researchers have made the first identification of a pair of genes in any species that are responsible for problems unique to hybrids. Specifically, the researchers have found two genes from two fruit fly species (Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans) that interfere with each other, thereby preventing the production of male offspring.

The finding may eventually shed light on what causes lethality or sterility in hybrids in general and, in a larger sense, offers clues to how species evolve from common ancestors. The research, published in Science, focuses on a rarely occurring mutation in a D. melanogaster gene called "Hmr" (Hybrid male rescue) and a similar mutation in a D. simulans gene called "Lhr" (Lethal hybrid rescue) that make these genes nonfunctional. When either of these genes is "turned off" and then crossed with the other fruit fly species, the males survive.

"We have found the first example of two genes that interact to cause lethality in a species hybrid," said the paper's senior author, Daniel Barbash, assistant professor in Cornell's Department of Molecular Biology and Genetics.

The finding supports the Dobzhansky-Muller model, a theory from the 1930s that suggests hybrid incompatibilities (such as death or sterility) are caused by genes that have evolved from a common ancestor but diverged in each of the species. More specifically, in the common ancestor, these genes may have worked perfectly well together. But, as each gene evolved in its own species, it began to code for proteins that no longer work in the other species. In this case, when genes from each species were compared with each other, the Hmr gene in D. melanogaster and the Lhr gene in D. simulans each evolved much faster than most other genes and diverged due to natural selection, a genetic change due to a pressure that benefits the survival of a species. The researchers would like to learn what these genes normally do within their species in order to understand why they are evolving so fast.

The Dobzhansky-Muller model also proposes that these evolved genes depend on each other to cause hybrid incompatibilities. However, when Barbash and his colleagues cloned each gene and inserted an Lhr gene from D. simulans into D. melanogaster, the two genes did not interfere with each other in the engineered D. melanogaster strain even though the Lhr and Hmr genes interfere with each other in hybrids. "This tells us there must be other things involved in the hybrid" that impacts the incompatible pairing of these genes, said Barbash. In future work the researchers hope to determine whether the hybrids die because of additional genes like Hmr and Lhr, or because of more subtle differences between the chromosomes of these two species.

Most read news

Topics

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.