A wandering eye

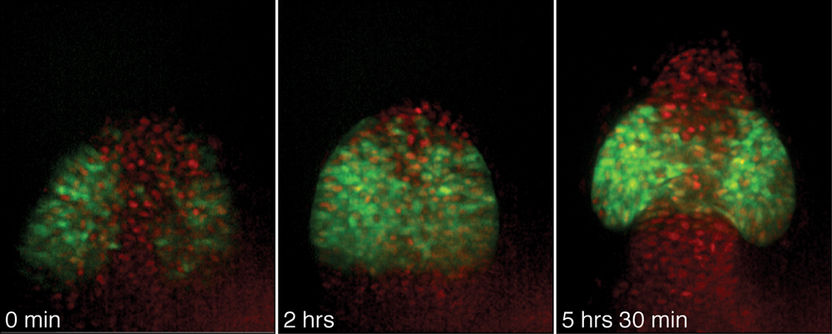

Eyes are among the earliest recognisable structures in an embryo; they start off as bulges on the sides of tube-shaped tissue that will eventually become the brain. Researchers from the European molecular biology Laboratory [EMBL] in Heidelberg have now discovered that cells are programmed to make eyes early in development and individually migrate to the right place to do so. The study, published in the journal Science, overturns the textbook model of the process and suggests that also other organs might be formed by the movement of single cells rather than sheets of entire tissues. Jochen Wittbrodt and his lab at EMBL made the discovery using advanced microscope techniques to track individual cells in the transparent embryos of a small fish called Medaka.

"You can think of the tube as a deflated balloon shaped like a Mickey Mouse," Wittbrodt says. "As the fish grows, the eyes gradually bulge out from the tube, the way Mickey Mouse ears expand as a balloon is filled with air. Most scientists have thought that cells in the neighbouring regions grow to make the bulges. What we've seen is that individual cells migrate to this area from the central region of the tube - as if to make ears, tiny rubber particles had to fly out from the air inside the balloon."

In 2001, Felix Loosli from Wittbrodt's laboratory discovered a protein called Rx3 that is required for eye formation. Only cells that will become the eye begin producing this molecule early on in development. Martina Rembold, also from Wittbrodt's group, labeled these cells with a fluorescent marker and tracked them using advanced software developed by Richard Adams at the University of Cambridge. Following the cells required recognizing them under the microscope and assembling tens of thousands of images into 3D movies.

"Rx3 plays a crucial role in giving the cells their identity and telling them where to go," says Rembold. "Normally, single cells migrate actively and one-by-one from the centre of the brain to form eyes. But in strains of fish that have no Rx3, no eyes develop and the cells remain inside the brain, because nothing tells them to migrate to the right place."

In the embryo the paths for cell movements are signposted by cues that by attracting or repelling different types of cells guide them into the right direction. Thanks to Rx3 eye cells prefer the cues guiding the way to the eye field. Following them the cells migrate individually against the stream of brain cells that are repelled by the same signal. Without Rx3 eye cells lose their preference and follow the bulk of brain cells into the other direction.

Many other organs are thought to form when sheets of nearby cells expand to form new shapes. The current study suggests that individual cell migration might be a more common phenomenon than scientists have suspected.

"We know that cell migration is important in the formation of many other organs, such as the heart," Wittbrodt says. "We'd like to understand how tissues originate and how cells move in the early embryo and to decipher the cues that tell them where to go. This approach of tracking individual cells will help us to understand these processes better."

Original publication: M. Rembold, F. Loosli, R.J. Adams, J. Wittbrodt.; "Individual cell migration as the driving force for optic vesicle evagination"; Science 2006.

Other news from the department science

These products might interest you

Limsophy by AAC Infotray

Optimise your laboratory processes with Limsophy LIMS

Seamless integration and process optimisation in laboratory data management

ERP-Software GUS-OS Suite by GUS

Holistic ERP solution for companies in the process industry

Integrate all departments for seamless collaboration

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.