Study Identifies Molecular Complex Vital to Creation of miRNAs

Possible Links to DiGeorge Syndrome, Schizophrenia Also Seen

Tiny bits of short-lived genetic material called microRNAs, or miRNAs, have attracted enormous interest from scientists since their discovery in humans only a few years ago. Viewed most broadly, they appear to play significant roles in controlling gene expression and development in many different settings.

Now, a new study from researchers at The Wistar Institute identifies for the first time a molecular complex vital for the creation of miRNAs. This complex, dubbed the microprocessor complex, contains two proteins, one of which has been linked to DiGeorge syndrome, the most common disorder of genetic deletion in humans. A swathe of DNA containing multiple genes is missing in DiGeorge syndrome patients, and many are born with heart defects, immune deficiencies, and developmental and behavioral problems. Intriguingly, one in four also goes on to develop schizophrenia, a disorder for which causative genes have yet to be identified. The new study appears in the November 11 issue of Nature.

"Discovery of this microprocessor complex gives us important insights into the processing mechanisms that generate miRNAs in the body," says Ramin Shiekhattar, Ph.D., an associate professor at Wistar and senior author on the Nature study. "At the same time, we see that one of the components of the complex is implicated in DiGeorge syndrome, suggesting that miRNA activity - or its lack - may be pivotal in the disease process of that multifaceted disorder."

The genes that code for miRNAs initially gives rise to a long primary RNA molecule that must first be cut into small precursor RNA molecules before final processing into mature miRNAs. The finished miRNAs are remarkably small, only 22 nucleotides in length, but powerful. These molecules appear to work by binding to complementary regions in messenger RNA, responsible for translating genes into proteins, or even to certain stretches of DNA. Either way, the result is gene silencing, which is one of the body's main strategies for regulating genes.

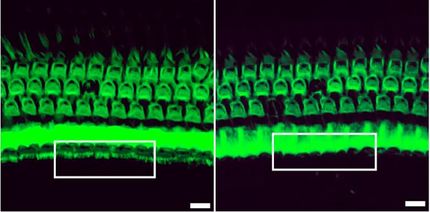

The microprocessor complex discovered by Shiekhattar's team is composed of two proteins called Drosha and DGCR8. Drosha had been previously identified as being involved in miRNA processing, but the role of DGCR8 is newly seen here. The Wistar scientists showed that both DGCR8 and Drosha were necessary for the processing of primary miRNA into a precursor miRNA - neither alone was sufficient to do the job. In another set of experiments, DGCR8 was intentionally inactivated, which led to excessive accumulations of the primary microRNA.

DGCR8 is one of the several genes deleted in DiGeorge syndrome, and this link suggests several paths for future investigations. Shiekhattar plans, for example, to develop a strain of mice lacking the gene for DGCR8 to see whether they display any of the characteristics of DiGeorge syndrome. He also aims to study DiGeorge syndrome patients to see whether they exhibit the excessive accumulations of primary RNA that might be expected due to a DGCR8-deficient, and therefore nonfunctional, microprocessor complex.

Scientists have noted, too, that miRNAs are critical for proper neuronal development. Might miRNA activity, then, provide a new window on schizophrenia, at least in DiGeorge syndrome patients, but perhaps also more globally?

"It would certainly be possible to look in schizophrenic populations for mutations in the DGCR8 gene," says Shiekhattar. "If those mutations were found, it could suggest of a significant role for miRNAs in schizophrenia."

In the course of their study of the microprocessor complex, the Wistar scientists also identified a second and much larger molecular complex that also incorporates Drosha. This complex contains about 20 proteins, and another goal for Shiekhattar's team in the future will be to ascertain the as-yet-unknown biological role of this complex.

Most read news

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.