Study describes basic mechanism in cell growth control involving damaged DNA

Chapel Hill. As interactions of cellular proteins increasingly take center stage in basic biomedical research, studies are revealing a complex molecular choreography with implications for human health and disease.

In a report currently appearing in the online issue of the journal Nature Cell Biology, scientists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine and the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center describe - for the first time - how some proteins interact to ensure that the cell does not continually divide when its DNA is damaged.

Although not yet clinically applicable, the study's findings offer new knowledge on how cells rapidly degrade unnecessary and potentially harmful proteins for recycling. They also point to a possible target for drug development: a cellular enzyme family involved in preventing replication of damaged genomic material.

"Inevitably, the molecular pathways controlling many cellular processes such as DNA repair must interact with those regulating cell division," said Dr. Yue Xiong, professor of biochemistry and biophysics at UNC. "An alteration in this critical interaction may be the cause of human cancer, which is characterized by deregulated cell cycle and accumulation of gene mutations."

Xiong, the report's senior author, added that a major goal of his UNC Lineberger laboratory is to understand the molecular mechanisms controlling cell cycle progression - the complex processes by which cells divide and DNA is replicated - and how this control becomes altered during tumor development.

Scientists have learned that the cell's ability to earmark proteins for recycling or degradation, often a target of cancer development, is key to controlling cell division.

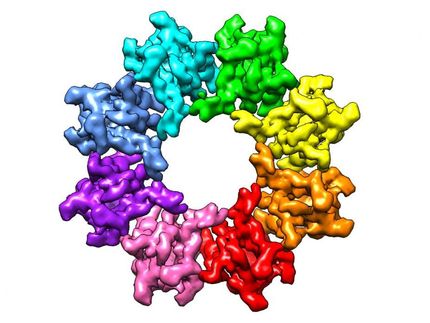

Xiong's laboratory has been studying a family of enzymes called E3 ubiquitin ligases. These ligases place a long tail of ubiquitin molecules on proteins, which are then slated for degradation and recycling. The degradation signaling process is set in motion when a protein is "misfolded" and cannot function properly.

Degradation also occurs when proteins of invading bacteria or viruses are recognized as faulty.

"In addition, the cell uses protein degradation as one major way to regulate its own activity, to rid itself of proteins no longer needed, including the tumor suppressor protein p53," said Xiong.

This protein stops the cell from growing or kills it, he added.

"If the cell is growing happily, it would not want p53 around. So it places ubiquitin on it, slating it for degradation, for recycling when it's needed."

In their current report, Xiong and UNC co-authors Jian Hu, Chad McCall and Dr. Tomohiko Ota focused on the ubiquitination pathway involving the family of enzymes called cullin-dependent ubiquitin ligases, specifically the ligase Cullin4 (CUL4).

The authors discovered that CUL4 figures prominently in a molecular pathway involving the "replication licensing factor" protein CDT1 and DDB1, or damaged DNA binding protein. DDB1 was discovered more than a decade ago as the DNA damage gene controlling Xeroderma pigmentosum, a rare hereditary disease involving a defect in DNA repair mechanisms induced by ultraviolet radiation.

The disease is characterized by severe sensitivity to all sources of UV radiation, especially sunlight. "CDT1 controls DNA replication, making sure DNA replicates once and only once," said Xiong. "But after replication, CDT1 must be degraded to prevent re-replication before the cell finishes dividing.

"And when DNA is damaged, the cell must find a way to very rapidly degrade CDT1 to prevent continued replication. And that job is carried out by the ubiquitin ligases."

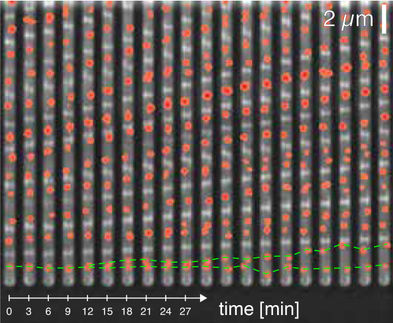

The new study for the first time shows how this molecular choreography occurs: DDB1 serves as a DNA damage "checkpoint" molecule, taking CDT1 to CUL4. The ligase then tags CDT1 with ubiquitin, and 15 minutes later, CDT1 gets degraded.

"This provides an explanation of how DDB1 may function to ensure the genetic stability and prevent cancer cell growth," said Xiong. "Our findings suggest that DDB1, by targeting CDT1 ubiquitination by the CUL4 ligase, may stop cells from proliferating when their DNA is damaged."

The new report also points to earlier observations that the gene encoding CUL4 is amplified in breast and liver cancer.

"We don't know the exact mechanism whereby CUL4 could play a role in cancer, but its abundance in the cell may cause a defect in the checkpoint pathway. And that's what we're studying now," said Xiong.