Social mobility: Study shows bacteria seek each other out

Findings could suggest new ways of attacking harmful bacteria

A study by Princeton University scientists has shown that bacteria actively move around their environments to form social organizations. The researchers placed bacteria in minute mazes and found that they sought each other out using chemical signals.

Biologists have become increasingly aware of social interactions among bacteria, but previously believed that clusters formed only when bacteria randomly landed somewhere, then multiplied into dense populations. The discovery that they actively move into gatherings underscores the importance of bacterial interactions and could eventually lead to new drugs that disrupt the congregating behavior of harmful germs, said Jeffry Stock, a professor of molecular biology and co-author of the paper.

"It makes sense, but it's surprising that it's as pervasive as it now seems to be," said Stock.

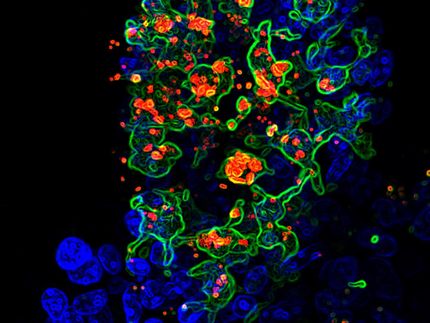

The researchers observed the gathering behavior in E. coli as well as in V. harveyi, a marine bacteria that glows when it achieves a high-density population. They found that when placed in mazes the bacteria congregated in small rooms and dead-end pathways. Once clustered, the V. harveyi turned on the genes that make them glow.

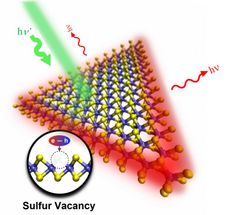

Biologists had previously believed that bacteria's ability to move and follow chemical signals -- a process called chemotaxis -- was primarily a means of dispersing and seeking food. The new study shows that chemotaxis may also be important for facilitating cooperative behavior.

The work was a collaboration between Stock's lab in biology and that of Robert Austin, a professor of physics. Emil Yuzbashyan, a graduate student in Austin's noticed unusual clumping when he put E. coli into microscopically small mazes made of silicone. Biologists in Stock's lab supplied mutant strains of bacteria that lacked genes necessary for sensing chemical signals and chemotaxis. They found that bacteria themselves emit a key chemical attractant and that those lacking the gene for the receptor that senses that attractant did not cluster as normal bacteria did.

Disrupting chemotaxis could be a route to attacking biofilms, a common type of bacterial interaction in which they form a colony that is resistant to antibiotic drugs and chemicals, the researchers said. Biofilms pose a common danger to patients receiving medical implants and cause trouble for ships that develop biofilms on their hulls.

Clustering also allows bacteria to perform a coordinated activity called quorum sensing in which they turn on certain genes only when they sense that they are part of a dense population. Some disease-causing bacteria are believed to rely on quorum sensing in mounting a successful infection. The V. harveyi in the experiment glowed as a result of quorum sensing after they gathered into a dense population.

"Our paper points out that you don't necessarily need growth to achieve quorum sensing," said Peter Wolanin, a postdoctoral researcher in Stock's lab. "The bacteria can actively seek each other out to engage in collective social behavior."

The behavior observed in the experiment also may have been a survival mechanism, said Sungsu Park, a postdoctoral researcher in Austin's lab and first author of the paper. The research was conducted with the bacteria in a nutrient-depleted environment that resembles the natural conditions for bacteria much of the time. "The bacteria are chasing amino acids released from their own cell bodies during starvation conditions," said Park. "So by getting close to each other they have a better chance of getting nutrients."

The researchers also have developed a mathematical model that simulates the bacterial congregation, said Park. They plan further research to investigate the relation between bacterial behavior and the size and geometry of their physical environment.

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.