Diatom ooze sediments are a large marine mercury sink

Sediments reveal mercury pollution in Antarctica since the beginning of the industrial period

Advertisement

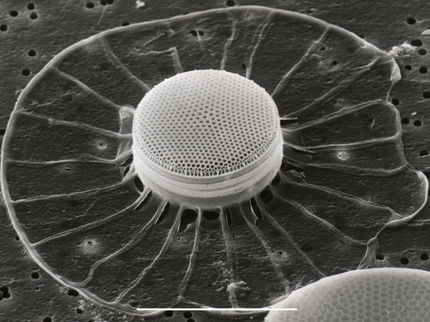

mercury has been used and released by humans by multiple processes such as gold and silver mining and emissions of mercury to the atmosphere by coal burning, to name the most important ones. These processes have caused strong enrichment of mercury in the environment especially in aquatic systems. However, the fate of mercury in the marine environment is barely understood. Scientists from Technical University of Braunschweig, Germany, investigated cores of biogenic sediments from marine Antarctica for accumulation of mercury in the past 8.000 years. They found out that microalgae (diatoms) accumulate high amounts of mercury in marine sediments and reveal onset and extent of global anthropogenic mercury emissions.

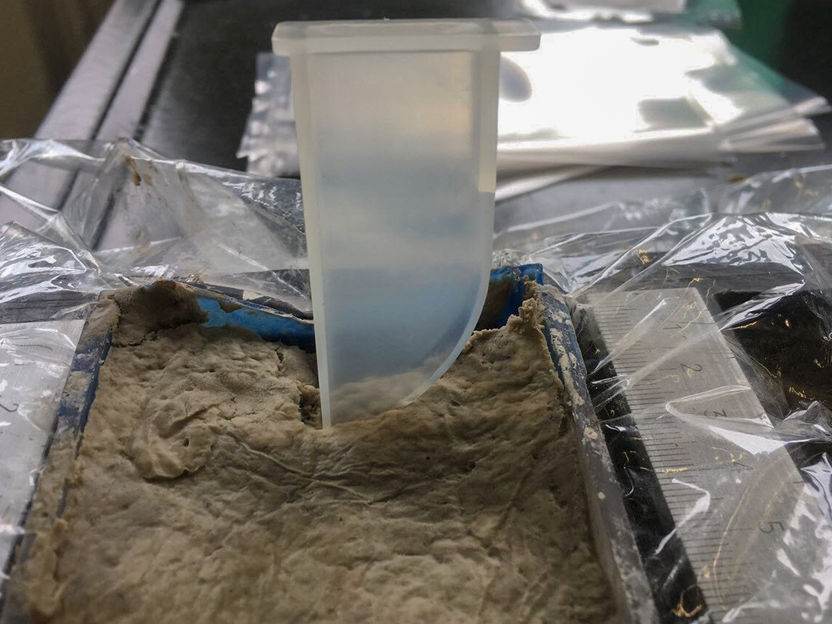

Sample acquisition from sediments

Sara Zaferani/TU Braunschweig

Atmospheric derived mercury is transformed in the ocean to toxic methylmercury, which is enriched in fish. Large marine predators such as tuna are strongly affected and even humans through fish consumption.

Up to now, no data on mercury accumulation in deep sea sediments has been available. Scientists from TU Braunschweig have now investigated the role of microalgae for mercury accumulation in biogenic marine sediments.

The environmental geochemistry group at the Institute of Geoecology at TU Braunschweig under direction of Prof Harald Biester has investigated marine bottom sediments which consist mainly of diatom remains (diatom ooze) for the historical accumulation of mercury. Those so called diatom ooze sediments are a result of algae blooms in the nutrient rich water of the Southern Ocean and form sediments of more than 100 m thickness with sedimentation rates of more than 1 cm per year.

With their analyses the scientists can show for the first time that diatom ooze accumulates large amounts of mercury in deep ocean sediments. Mercury accumulation rates derived from sediment cores from marine Antarctica are the highest ever reported for the marine environment.

Calculations based on the silicon/mercury ratio in the investigated sediment cores as well as literature data on global diatom ooze sedimentation reveal that between 9 and 20 percent of the annually emitted mercury from industrial sources could have been buried by diatoms alone. Moreover, diatom ooze could have been accumulated between 6,5 and 20 percent of all mercury emitted to the atmosphere during the industrial period. These results highlight the important role of algae for the accumulation of mercury in marine sediments.

The high resolution (10-40 years) historical mercury record (8.600 years) derived from Adélie Basin (marine Antarctica) sediments indicates that anthropogenic mercury pollution in Antarctica started with the beginning of the industrial period at around 1850 AD. Earlier emissions, for example from colonial gold and silver mining in the 16th century where mercury was used for the extraction of the precious metals, could not be detected. Overall, the publication presents new important results for the global distribution of mercury emitted from anthropogenic sources and its enrichment in the marine food chain.