Mapping chemicals in the skin

Reducing animal experiments with chemical imaging

Advertisement

A new method of examining the skin can reduce the number of animal experiments while providing new opportunities to develop pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. chemical imaging allows all layers of the skin to be seen and the presence of virtually any substance in any part of the skin to be measured with a very high degree of precision.

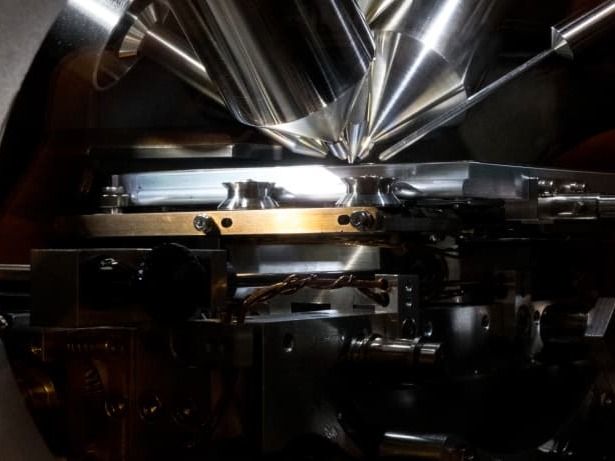

Specimen holders in which the skin samples are mounted for analysis.

Mats Tiborn

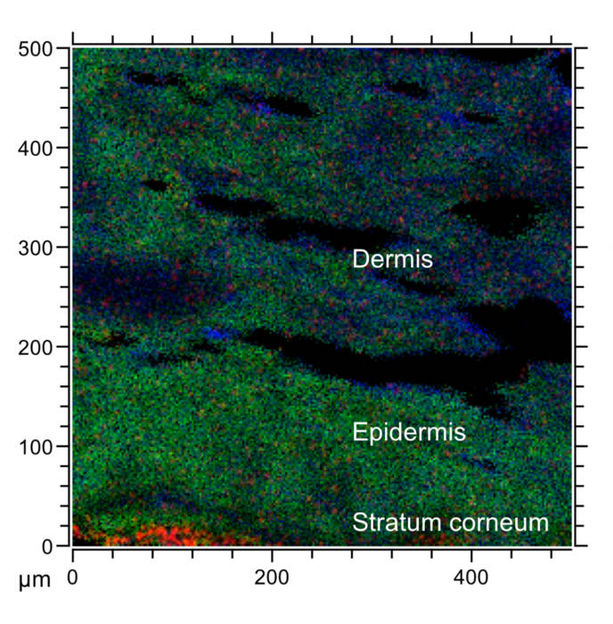

3D imaging of a skin section in which the nickel content is being measured. The red area represents the presence of nickel.

Per Malmberg

Chemists Lina Hagvall and Per Malmberg prepare samples for analysis in the time-of flight secondary ion mass spectrometer (ToF-SIMS). During analysis the samples are inserted into the test chamber using the test arm shown at the bottom of the picture.

Mats Tiborn

More and more chemicals are being released into our environment. For example, parabens and phthalates are under discussion as two types of chemicals that can affect us. But so far it has not been possible to find out how they are absorbed by the skin. A new study from Chalmers University of Technology and the University of Gothenburg shows how what is termed chemical imaging can provide comprehensive information about the human skin with a very high level of precision.

Investigations into how substances pass into and through the skin have so far taken place in two ways: by using tape strips to pull off the top “corneal” layer of skin for analysis, and through urine and blood testing to see what has penetrated through the skin. But we still know very little about what happens in the layers of skin in between. Chemical imaging now allows us to see all layers of the skin with very high precision and to measure the presence of virtually any substances in any part of the skin. This can lead to pharmaceutical products that are better suited to the skin, for example.

The new method was created when the chemists Per Malmberg, at Chalmers University of Technology, and Lina Hagvall, at the University of Gothenburg, brought their areas of research together.

“With pharmaceuticals you often want as much as possible of the dose to be absorbed by the skin, but in some cases you may not want skin absorption, such as when you apply a sunscreen, which needs to remain on the surface of the skin and not penetrate it. Our method allows you to design pharmaceuticals according to the way you want the substance to be absorbed by the skin,” says Hagvall.

Chemical imaging has until now mainly been used for earth sciences and cellular imaging, but with access to human skin from operations the researchers have come up with this new area for the technology. The researchers now also see opportunities opening up for replacing pharmaceutical tests which currently involve animal experiments. Their methods provide more accurate results than tests on mice and pigs. Since it is not permissible to use animals to test cosmetics, this method may also create new opportunities for the cosmetics industry.

“Many animal experiments carried out by researchers and companies are no longer necessary as a result of this method. If you want to know something about passive absorption into the human skin, this method is at least as good. It’s better to do your testing on human skin than on a pig,” says Hagvall.

The new method can also provide a basis for determining the correct limits for harmful levels of substances that may come into contact with the skin. In order to establish those limits, you need to know how much of the dose on the skin’s surface penetrates into and through the skin, which this method can show. It enhances our knowledge about what we are absorbing in our workplaces and in childcare facilities.

“Our method can show everything with an image, whether you are looking for nickel, phthalates or parabens in the skin, or if you want to follow the drug’s path through the skin. With just a skin sample we can essentially search for any molecules. We don’t need to adapt the method in advance to what we are looking for,” says Malmberg.

It will be possible to apply the results in the very near future. The technology itself is ready for use today. There is still a small amount of work left to do in optimising the tests to achieve the best results, but the researchers believe that the method will be ready for use within a year.

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Most read news

More news from our other portals

See the theme worlds for related content

Topic World Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry enables us to detect and identify molecules and reveal their structure. Whether in chemistry, biochemistry or forensics - mass spectrometry opens up unexpected insights into the composition of our world. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of mass spectrometry!

Topic World Mass Spectrometry

Mass spectrometry enables us to detect and identify molecules and reveal their structure. Whether in chemistry, biochemistry or forensics - mass spectrometry opens up unexpected insights into the composition of our world. Immerse yourself in the fascinating world of mass spectrometry!