Stem cell transplants to be used in treating Crohn's disease

Growing a new immune system

A clinical trial has begun which will use stem cell transplants to grow a new immune system for people with untreatable Crohn's disease - a painful and chronic intestinal disease which affects at least 115,000 people in the UK.

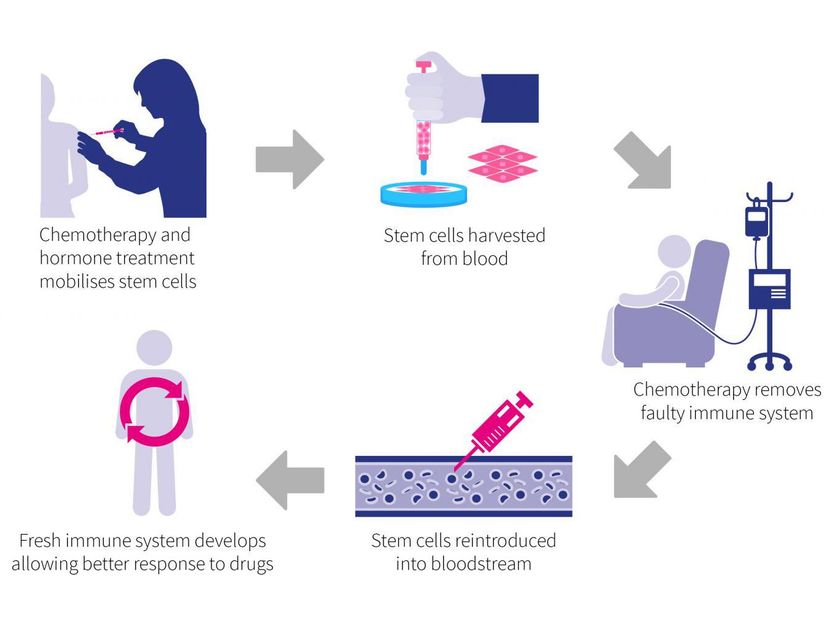

Diagram of stem cell therapy

Queen Mary University of London

The study, led by Queen Mary University of London and Barts Health NHS trust, is funded with £2m from a Medical Research Council and National Institute for Health Research partnership, and will be recruiting patients from centres in Cambridge, Edinburgh, Liverpool, London, Nottingham, Oxford and Sheffield. The trial is coordinated through the Clinical Trials Unit at the University of Sheffield.

Crohn's disease is a long-term condition that causes inflammation of the lining of the digestive system, and results in diarrhoea, abdominal pain, extreme tiredness and other symptoms that significantly affect quality of life.

Current treatments include drugs to reduce inflammation but these have varying results, and surgery is often needed to remove the affected part of the bowel. In extreme cases, after multiple operations over the years, patients may require a final operation to divert the bowel from the anus to an opening in the stomach, called a stoma, where stools are collected in a pouch.

Chief investigator Professor James Lindsay from Queen Mary University of London and a consultant at Barts Health NHS Trust said: "Despite the introduction of new drugs, there are still many patients who don't respond, or gradually lose response, to all available treatments. Although surgery with the formation of a stoma may be an option that allows patients to return to normal daily activities, it is not suitable in some and others may not want to consider this approach.

"We're hoping that by completely resetting the patient's immune system through a stem cell transplant, we might be able to radically alter the course of the disease. While it may not be a cure, it may allow some patients to finally respond to drugs which previously did not work."

Helen Bartlett, a Crohn's disease patient who had stem cell therapy at John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, said: "Living with Crohn's is a daily struggle. You go the toilet so often, you bleed a lot and it's incredibly tiring. You also always need to be careful about where you go. I've had to get off trains before because there's been no toilet, and I needed to go there and then.

"I've been in and out of hospital for the last twenty years, operation after operation, drug after drug, to try to beat this disease. It's frustrating, it's depressing and you just feel so low.

"When offered the stem cell transplant, it was a complete no brainer as I didn't want to go through yet more failed operations. I cannot describe how much better I feel since the treatment. I still have problems and I'm always going to have problems, but I'm not in that constant pain."

The use of stem cell transplants to wipe out and replace patients' immune systems has recently been found to be successful in treating multiple sclerosis. This new trial will investigate whether a similar treatment could reduce gut inflammation and offer hope to people with Crohn's disease.

In the trial, patients undergo chemotherapy and hormone treatment to mobilise their stem cells, which are then harvested from their blood. Further chemotherapy is then used to wipe out their faulty immune system. When the stem cells are re-introduced back into the body, they develop into new immune cells which give the patient a fresh immune system.

In theory, the new immune system will then no longer react adversely to the patient's own gut to cause inflammation, and it will also not act on drug compounds to remove them from their gut before they have had a chance to work.

Professor Tom Walley, Director of the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies programmes, which funded the trial, said: "Stem cell therapies are an important, active and growing area of research with great potential. There are early findings showing a role for stem cells in replacing damaged tissue. In Crohn's disease this approach could offer real benefits for the clinical care and long term health of patients."

The current clinical trial, called 'ASTIClite', is a follow up to the team's 2015 'ASTIC' trial, which investigated a similar stem cell therapy. Although the therapy in the original trial did not cure the disease, the team found that many patients did see benefit from the treatment, justifying a further clinical trial. There were also some serious side effects from the doses of drugs used, so this follow-up trial will be using a lower dose of the treatment to minimise risks due to toxicity.