Bacteria may help babies' digestive tracts more than suspected, scientists find

Advertisement

Some of the first living things to greet a newborn baby do a lot more than coo or cuddle. In fact, they may actually help the little one's digestive system prepare for a lifetime of fighting off dangerous germs.

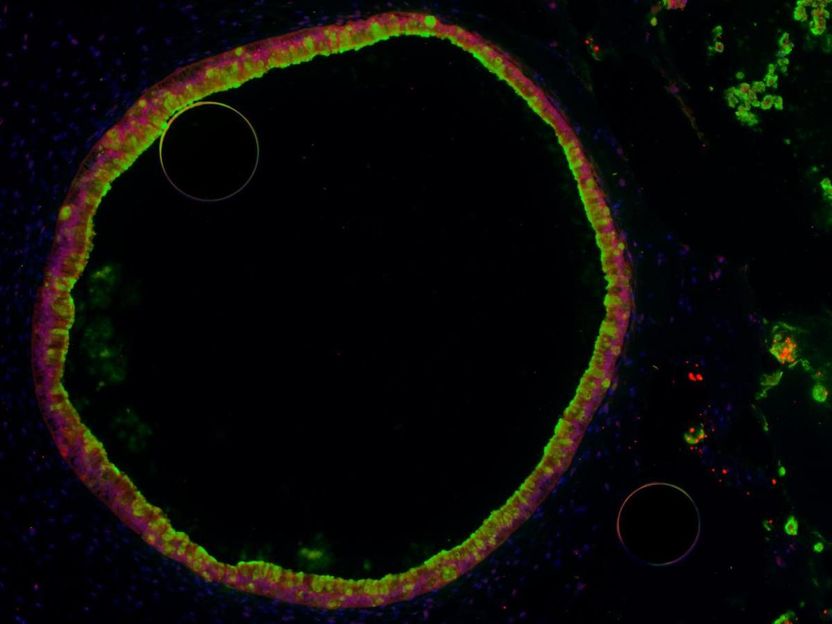

A single human intestinal organoid, or HIO -- a hollow ball of cells grown from human embryonic stem cells and coaxed to become gut-lining cells. Scientists can use it to study basic gut development, and the effect of microbes on the cells, in a way that mimics the guts of newborn babies.

University of Michigan

But these living things aren't parents, grandparents or siblings - they're helpful bacteria. And new research suggests they may help the lining of the newborn gut prepare for the surge of other bacteria that will soon make up the thriving and diverse population of microbes that lives within each of us all our lives.

A team from the University of Michigan Medical School reports their findings about the impact of a helpful strain of Escherichia coli on the cells that line the gut.

They conclude that non-pathogenic E. coli serves a crucial function of preparing the gut for the development of the microbiome to come, and the onslaught of pathogenic, or harmful, microbes.

The new results may help explain what past research has shown about the connection between the gut microbiome and the development of the newborn immune system. They may also lead to better understanding of what can protect or rescue premature newborns from a rare but devastating gut infection condition called necrotizing enterocolitis.

Mini guts to stand in for little guts

To do the research, the team chose a strain of E. coli related to ones that are commonly found in many newborn babies' used diapers. In other words, it's one of the pioneers that initially settle in the digestive tract.

The researchers couldn't do their research in actual newborns' intestines, of course. Instead, they used stem cells to grow miniature versions of the gut lining, called human intestinal organoids.

Each HIO, as they're called, is made up of thousands of cells that the scientists coax to grow, divide and organize into structures that resemble the actual gut. At each HIO's center is a hollow area called a lumen, which mimics the hollow inner portion of the tube-like human intestine.

"We have previously shown that HIOs closely resemble the immature human intestine," explains lead author David Hill, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in gastroenterology at U-M. "In this study, we wanted to discover the effects of colonization on the intestine with a non-harmful strain of E. coli, a type of bacteria that is commonly found in the guts of newborn babies."

During growth, they kept these HIOs germ-free, just like the gut of a fetus in the womb. Then, they introduced the helpful E. coli into the hollow center of the organoids. They tracked what happened inside the cells whose surfaces face the center, and in the spaces between the cells. They looked at how the cells were altering gene activity over time in response to the introduction of E. coli.

The results were clear. After the scientists introduced the E. coli, the cells facing the lumen began to mature, form tighter connections with one another, and produce mucus to coat their surface.

Genes involved in cell-to-cell communication, and the physical structures cells use to link with their neighbors, became active. So did genes involved in making antimicrobial substances and mucus and transporting them to the cell surface, and in adaptation to low oxygen - which is caused by bacterial metabolism and is a hallmark of the mature adult intestine.

This activity led the HIOs to develop better resistance to inflammation-causing stimuli, which meant less damage to the cells lining the lumen.

"Our results show that colonization of the immature intestinal tract with E. coli results in intestinal tissue that is more robust to challenge by potentially damaging pathogens or inflammatory substances," concludes senior author Jason Spence, Ph.D., an associate professor of internal medicine and of cell and developmental biology at U-M.

Co-senior author Vincent Young, M.D., Ph.D., adds, "We have developed a system that faithfully reproduces the physiology of the immature human intestine, and will now make it possible to study a range of host-microbe interactions in the intestine to understand their functional role in health and disease." Young is a professor of internal medicine who specializes in infectious diseases at Michigan Medicine, U-M's academic medical center, and is also a professor of microbiology and immunology.

The research grew out of cooperation between the Spence lab, which focuses on HIOs, and the Young lab, which focuses on the gut microbiome. The work was made possible by funding from the National Institutes of Health, and by investments the Medical School has made in tools that help with organoid, microbiome and DNA sequencing research.

Even as the new paper comes out, the team already has more work under way, to study additional strains of non-harmful E. coli and other bacteria that take up long-term residence in the newborn gut, as well as pathogens.

"We hope to examine whether different bacteria produce different types of responses in the gut," says Hill. "This type of work might help to explain why different types of gut bacteria seem to be associated with positive or negative health outcomes."

The Spence team is preparing to launch a "core" service to provide HIOs for other researchers to study.

Original publication

Hill, David R; Huang, Sha; Nagy, Melinda S; Yadagiri, Veda K; Fields, Courtney; Mukherjee, Dishari; Bons, Brooke; Dedhia, Priya H; Chin, Alana M; Tsai, Yu-Hwai; Thodla, Shrikar; Schmidt, Thomas M; Walk, Seth; Young, Vincent B; Spence, Jason R; "Bacterial colonization stimulates a complex physiological response in the immature human intestinal epithelium"; eLife; 2017