'Squirtable' elastic surgical glue seals wounds in 60 seconds

A highly elastic and adhesive surgical glue that quickly seals wounds without the need for common staples or sutures could transform how surgeries are performed.

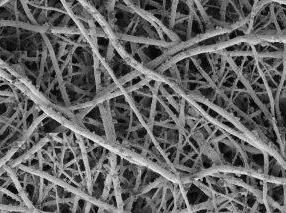

MeTro is applied directly to the wound and activated with light.

University of Sydney

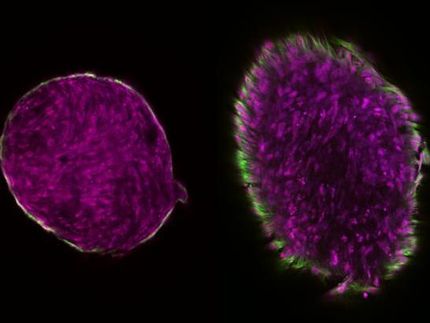

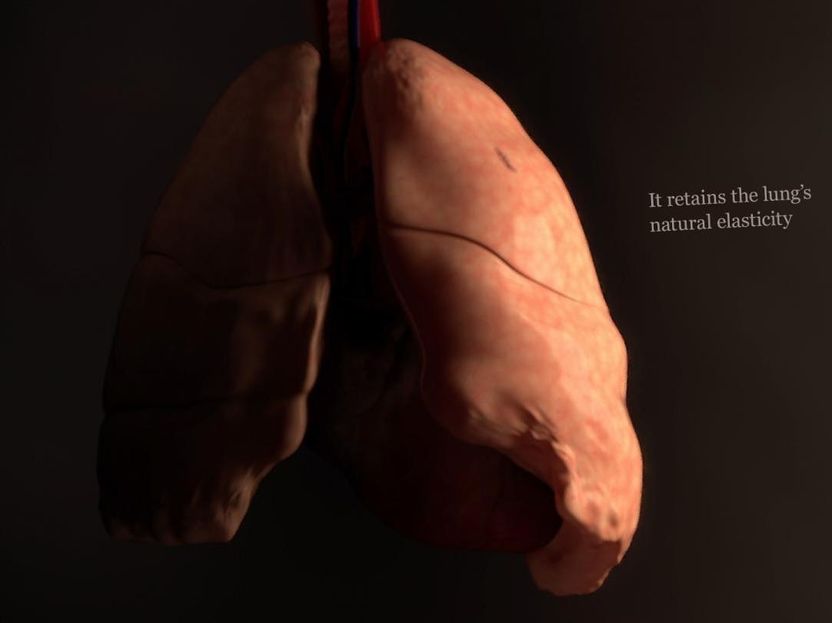

It retains the lung's natural elasticity.

University of Sydney

Biomedical engineers from the University of Sydney and the United States collaborated on the development of the potentially life-saving surgical glue, called MeTro.

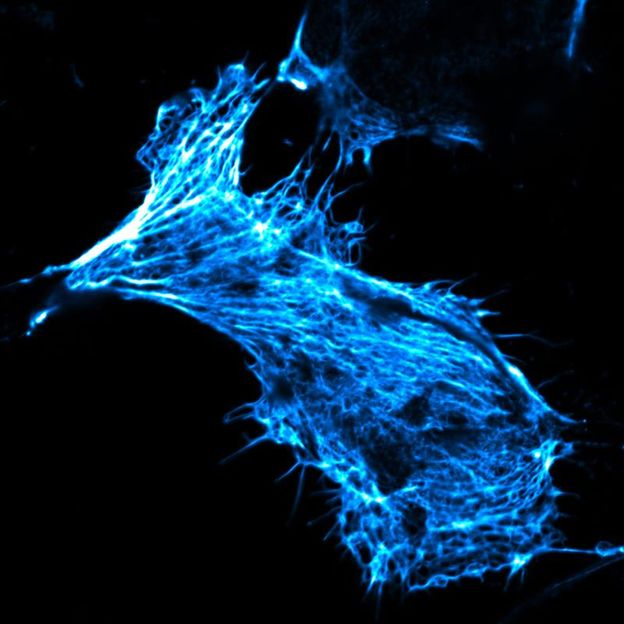

MeTro's high elasticity makes it ideal for sealing wounds in body tissues that continually expand and relax - such as lungs, hearts and arteries - that are otherwise at risk of re-opening.

The material also works on internal wounds that are often in hard-to-reach areas and have typically required staples or sutures due to surrounding body fluid hampering the effectiveness of other sealants.

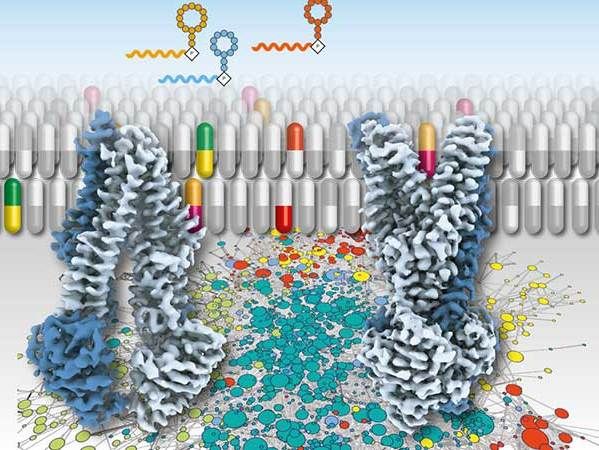

MeTro sets in just 60 seconds once treated with UV light, and the technology has a built-in degrading enzyme which can be modified to determine how long the sealant lasts - from hours to months, in order to allow adequate time for the wound to heal.

The liquid or gel-like material has quickly and successfully sealed incisions in the arteries and lungs of rodents and the lungs of pigs, without the need for sutures and staples.

The results were published by the University of Sydney's Charles Perkins Centre and Faculty of Science; Boston's Northeastern University, the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) in Boston.

MeTro combines the natural elastic protein technologies developed in collaboration with author and University of Sydney McCaughey Chair in Biochemistry Professor Anthony Weiss, with light sensitive molecules developed in collaboration with author and Director of the Biomaterials Innovation Research Center at Harvard Medical School Professor Ali Khademhosseini.

Lead author of the study, Assistant Professor Nasim Annabi from the Department of Chemical Engineering at Northeastern University, oversaw the application of MeTro in a variety of clinical settings and conditions.

"The beauty of the MeTro formulation is that, as soon as it comes in contact with tissue surfaces, it solidifies into a gel-like phase without running away," she said.

"We then further stabilise it by curing it on-site with a short light-mediated crosslinking treatment. This allows the sealant to be very accurately placed and to tightly bond and interlock with structures on the tissue surface."

The University of Sydney's Professor Anthony Weiss described the process as resembling that of silicone sealants used around bathroom and kitchen tiles.

"When you watch MeTro, you can see it act like a liquid, filling the gaps and conforming to the shape of the wound," he said.

"It responds well biologically, and interfaces closely with human tissue to promote healing. The gel is easily stored and can be squirted directly onto a wound or cavity.

"The potential applications are powerful - from treating serious internal wounds at emergency sites such as following car accidents and in war zones, as well as improving hospital surgeries."

Professor Khademhosseini from Harvard Medical School was optimistic about the study's findings.

"MeTro seems to remain stable over the period that wounds need to heal in demanding mechanical conditions and later it degrades without any signs of toxicity; it checks off all the boxes of a highly versatile and efficient surgical sealant with potential also beyond pulmonary and vascular suture and staple-less applications," he said.

The next stage for the technology is clinical testing, Professor Weiss said.

"We have shown MeTro works in a range of different settings and solves problems other available sealants can't. We're now ready to transfer our research into testing on people. I hope MeTro will soon be used in the clinic, saving human lives."

Original publication

Annabi, Nasim and Zhang, Yi-Nan and Assmann, Alexander and Sani, Ehsan Shirzaei and Cheng, George and Lassaletta, Antonio D. and Vegh, Andrea and Dehghani, Bijan and Ruiz-Esparza, Guillermo U. and Wang, Xichi and Gangadharan, Sidhu and Weiss, Anthony S. and Khademhosseini, Ali; "Engineering a highly elastic human protein-based sealant for surgical applications"; Science Translational Medicine; 2017