Drug design strategy boosts the odds against resistance development

Advertisement

A new rational drug design technique that uses a powerful computer algorithm to identify molecules that target different receptor sites on key cellular proteins could provide a new weapon in the battle against antibiotic resistance, potentially tipping the odds against the bugs.

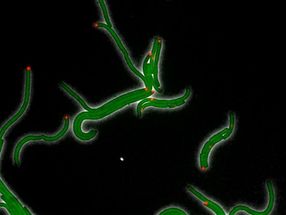

This image shows E. coli cells under the stress of DHFR-targeting antibiotic trimethoprim in a 2015 study done prior to the research reported in this paper. The green color comes from GFP protein fused to DHFR and shows the uniform distribution of DHFR. The red color shows location of inclusion bodies of aggregated proteins in the cell.

Courtesy of Eugene Shakhnovich

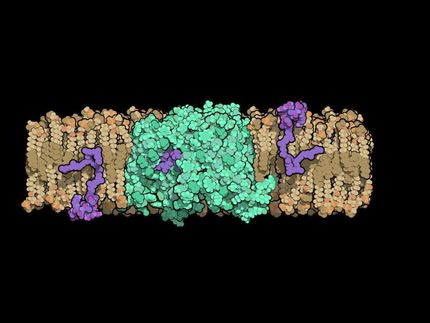

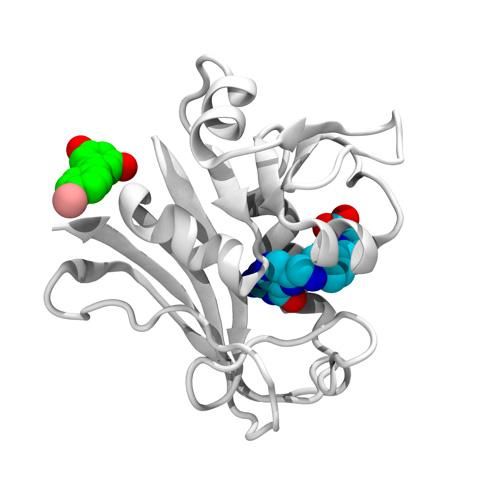

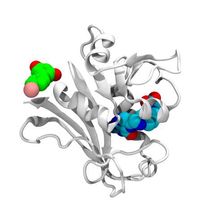

This is the structure of the E. coli DHFR protein (white) with its folate (blue) present at the enzymatic pocket and bromo-resveratrol (green) bound at the potential allosteric site responsible for antibiotic activity in escape variants of E. coli.

Courtesy of Jeffrey Skolnick

The technique, which has been validated against a drug-resistant bacterial strain, identifies compounds that target two or more receptor sites on proteins that inhibit a key cellular function. To obtain resistance to drug compounds developed with the technique, the microbes would have to simultaneously develop mutations in all the receptor pockets targeted by the drug - a challenge much more significant than developing resistance in a single receptor site.

Researchers from the Georgia Institute of Technology and Harvard University believe the technique could provide a new general approach for battling drug resistance that may potentially also be applied to cancer cells and viruses which also develop drug resistance.

"We have developed an entirely novel mechanism for increasing antibiotic effectiveness," said Jeffrey Skolnick, director of Georgia Tech's Center for the Study of Systems Biology. "The problem of emerging antibiotic resistance is a major health care crisis, and we think this approach could allow the rapid design of new classes of molecules that would be able to maintain their effectiveness longer, allowing us to stay one step ahead of the bugs."

Antibiotic resistance often develops when proteins - often enzymes - mutate the receptor pockets that allow the drugs to bind to the protein. Bacterial populations often include individuals that have these mutations randomly, and when antibiotics kill off the susceptible cells, the population of those with the specific mutation grows. In order to control these resistant bacteria, doctors must employ a drug compound that targets a different receptor or different binding site on a key bacterial protein.

The technique identified three classes of inhibitor drugs that targeted both primary and secondary receptor pockets on the dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) enzyme in a drug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli (E. coli). DHFR is necessary for the synthesis of important cellular building blocks, and is a classical target for antibiotics. Without production of these compounds, bacteria cannot reproduce.

Using their algorithm, Skolnick and his Georgia Tech collaborators identified 10 potentially useful drug compounds and prioritized compounds from the three categories - stilbenoid, deoxybenzoin and chalcone family of compounds - for their ability to target a secondary receptor pocket. Interestingly, one of the molecules was resveratrol which is found in red wine and which has been reported to have anti-aging and anti-cancer effects. In the laboratory, the researchers confirmed that the commercially available compounds could indeed bind with DHFR.

But the real test was whether the compounds would work on living bacteria. To evaluate that, the Georgia Tech researchers worked with Eugene Shakhnovich, a professor in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology at Harvard University. Shakhnovich and his colleagues confirmed that the drug compounds shut down the production of folates in the drug-resistant E. coli, dramatically slowing the growth of the bacterium. They also showed that the addition of folates to the bacterial population allowed the bugs to survive despite treatment by the DHFR-inhibiting drugs.

"We tested the compounds in vitro with purified variants of the enzyme," Shakhnovich said. "We engineered E. coli strains that carry escape mutations in the folA locus - which encodes DHFR - on their chromosomes and proved that the newly-found compounds effectively inhibit growth in both wild-type and escape mutant strains of DHFR, albeit at high concentrations."

Because it is a relatively small protein with well-defined biophysical properties, DHFR "represents a desirable model to explore the genotype-phenotype relationship between biophysical properties of the enzyme and the fitness and evolution of a microorganism," Shakhnovich added.

As a next step, Skolnick would like to test the principle on other proteins essential to other microorganisms to see if two or more binding pockets can be targeted. That could require development of new therapeutic molecules able to attack the microbial targets. Ultimately, the technique could be used to shut down other avenues of antibiotic resistance, including the ability of cells to break down drugs or eject them before they can bind.

If the technique proves successful in other laboratory studies, testing with an animal model would be necessary to determine whether it can be beneficial in living organisms.

DHFR has been targeted for anti-cancer drugs, and Skolnick is hopeful that the two-receptor technique may prove useful in developing new chemotherapy agents that could fight off the resistance that often renders them useless.

Skolnick believes the approach may help scientists stay ahead of bacterial resistance by providing a technique to rapidly develop new drugs. The compounds would be used in combination therapies to further guard against development of resistance.

"We are always going to be at war with microbes," he said. "The bacterial system is going to evolve to respond to new antibiotics, so we have to keep targeting something else so the system never gets to evolve resistance. It's likely that we'll need to use combination therapies that use multiple drugs to eliminate the development of resistance."