New technique could increase success rate, life span of implantable devices

A new technique being developed at Purdue University could provide patients who require implantable catheters in the treatment of neurological and other disorders with a reliable and self-clearing catheter that could eliminate the need for additional surgery to replace failing devices.

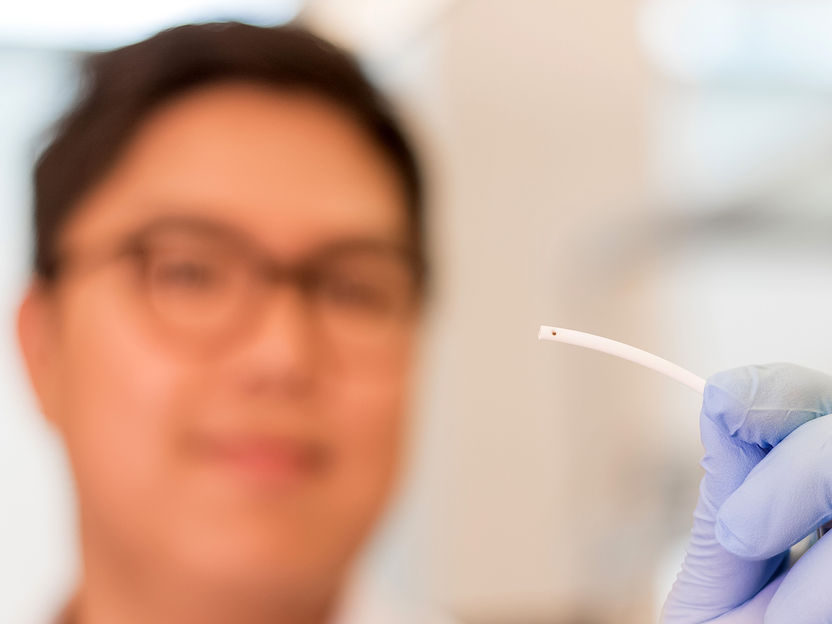

Hyowon Lee, an assistant professor in Purdue’s Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering, holds up a smart self-clearing catheter in the form of microscale devices on a paper-thin film that can be assembled into existing catheters. The device could provide a reliable alternative to conventional high-failure devices that require additional surgery to remove.

Trevor Mahlmann

“Implantable catheters are used to treat a number of neurological and cardiac disorders by either diverting excess fluid or for delivering drugs. Specifically, catheters can greatly benefit patients with hydrocephalus, a neurological disorder that is often characterized by a large accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain,” said Hyowon “Hugh” Lee, an assistant professor in Purdue’s Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering and developer of the technology. “Over 1 million people in the U.S. suffer from hydrocephalus, and one to two newborns develop the disorder every 1,000 births. Patients can also acquire hydrocephalus later in life from traumatic brain injury or hemorrhagic stroke. Hydrocephalus can cause an enlarged head in children and many other life-altering physical, behavioral and cognitive symptoms in children and adults alike.”

Lee said existing implantable catheters have a high failure rate that requires additional surgery or intervention.

“When a catheter is implanted, the body’s natural reaction is to protect itself against the foreign material by forming a sheath around it. Biofouling materials including bacteria, blood and inflammatory cells, and other tissue quickly cover the device, often blocking the catheter’s inlet pores leading to premature device failure,” he said. “Approximately 40 percent of shunt systems fail within one year of implantation, and 85 percent fail within 10 years, mostly due to catheter obstruction. Replacing the failed catheter usually requires a neurosurgery, which increases the risk of infection and has a huge economic, physical, and emotional burden for patients and their caretakers.”

The technology being developed by Lee is a smart self-clearing catheter in the form of microscale devices on a paper-thin film that can be assembled into existing catheters. The technology has tiny magnetic elements on top of micromechanical devices that uses magnetic force to remove biomaterials that attach to the catheter.

“When you have a compass and you put a magnet nearby it, you can make the needle move. There are a couple different ways for magnetic actuation, but one is to make it torque like a seesaw,” Lee said. “That’s what we essentially do with our device integrated into catheters. The micro-device is fixed at an anchor point, and we apply magnetic field from outside the body. By using time-varying magnetic field, changing its magnitude or turning it on or off, you create dynamic movement and mechanical vibration at the pore to be able to remove the obstructive biomaterials. The magnetic approach is ideal for this application because it generates a large amount of force and can be done without an integrated circuit or power source. This makes it much simpler and reduces the burden of hermetic packaging for implantation.”

Lee said the technology is currently undergoing further testing.

“We have demonstrated the efficacy of the device with providing enough force to be able to remove the different types of biomaterial,” Lee said. “We are currently testing these self-clearing catheters for in-vitro and in-vivo evaluations and are actively working on new devices for other types of indwelling catheter applications.”

A similar device is also in the works for better treatment of glaucoma, Lee added.

“Glaucoma patients have similar problems with pressure buildup inside their eye. More patients are undergoing surgical procedures to implant drainage devices to remove excess vitreous humor and lower intraocular pressure,” he said. “We are creating even smaller magnetic micro-actuators that go into the glaucoma drainage device tubes. This will address the issue of biomaterial obstruction that these devices face as well.”