'Persistent photoconductivity' offers new tool for bioelectronics

Researchers at North Carolina State University have developed a new approach for manipulating the behavior of cells on semiconductor materials, using light to alter the conductivity of the material itself.

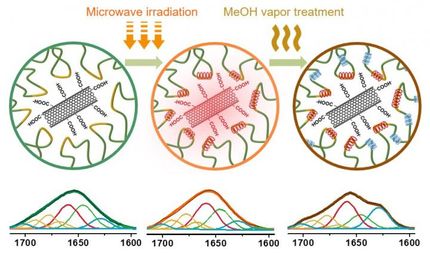

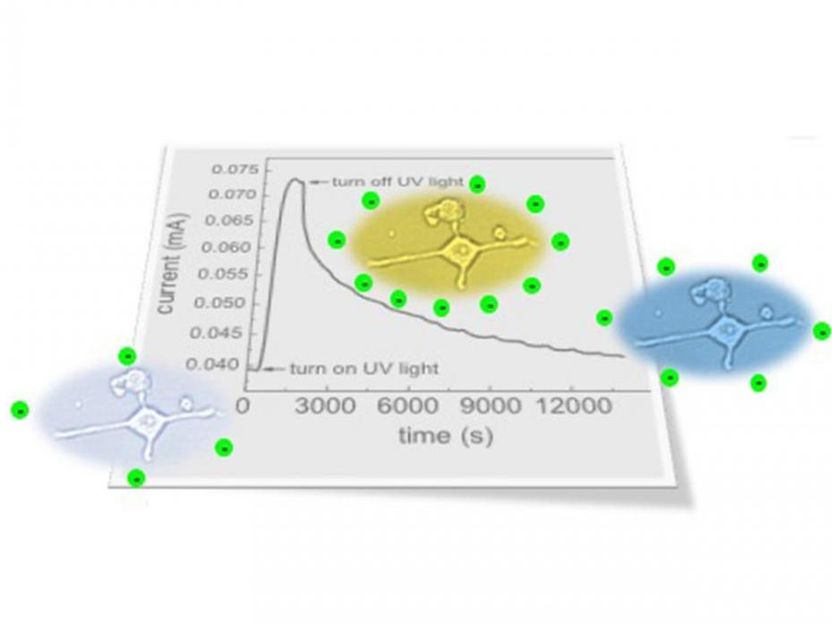

This image illustrates changes in photocurrent before and after exposure to UV light. Persistent photoconductivity is demonstrated even hours after the UV light has been turned off. This is illustrated by the pictograms showing charge carriers that come into contact with cells at the interface during in vitro experiments.

Albena Ivanisevic

"There's a great deal of interest in being able to control cell behavior in relation to semiconductors - that's the underlying idea behind bioelectronics," says Albena Ivanisevic, a professor of materials science and engineering at NC State and corresponding author of a paper on the work. "Our work here effectively adds another tool to the toolbox for the development of new bioelectronic devices."

The new approach makes use of a phenomenon called persistent photoconductivity. Materials that exhibit persistent photoconductivity become much more conductive when you shine a light on them. When the light is removed, it takes the material a long time to return to its original conductivity.

When conductivity is elevated, the charge at the surface of the material increases. And that increased surface charge can be used to direct cells to adhere to the surface.

"This is only one way to control the adhesion of cells to the surface of a material," Ivanisevic says. "But it can be used in conjunction with others, such as engineering the roughness of the material's surface or chemically modifying the material."

For this study, the researchers demonstrated that all three characteristics can be used together, working with a gallium nitride substrate and PC12 cells - a line of model cells used widely in bioelectronics testing.

The researchers tested two groups of gallium nitride substrates that were identical, except that one group was exposed to UV light - triggering its persistent photoconductivity properties - while the second group was not.

"There was a clear, quantitative difference between the two groups - more cells adhered to the materials that had been exposed to light," Ivanisevic says.

"This is a proof-of-concept paper," Ivanisevic says. "We now need to explore how to engineer the topography and thickness of the semiconductor material in order to influence the persistent photoconductivity and roughness of the material. Ultimately, we want to provide better control of cell adhesion and behavior."

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.