Cellular 'tuning mechanism' builds elegant eyes

A molecular 'brake' that helps control eye lens development in zebrafish

Advertisement

How different cells in a multicellular organism acquire their identities remains a fundamental mystery of development. In the eye, for example, the lens contains two cell types - lens epithelial cells and lens fiber cells -- the first of which differentiates into the second as an animal matures. Scientists have long known that fibroblast growth factor, or FGF, acts as the main gas pedal for this process. Now, scientists at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) have discovered that a different molecular signal acts as a brake pedal, preventing cells from differentiating where they shouldn't.

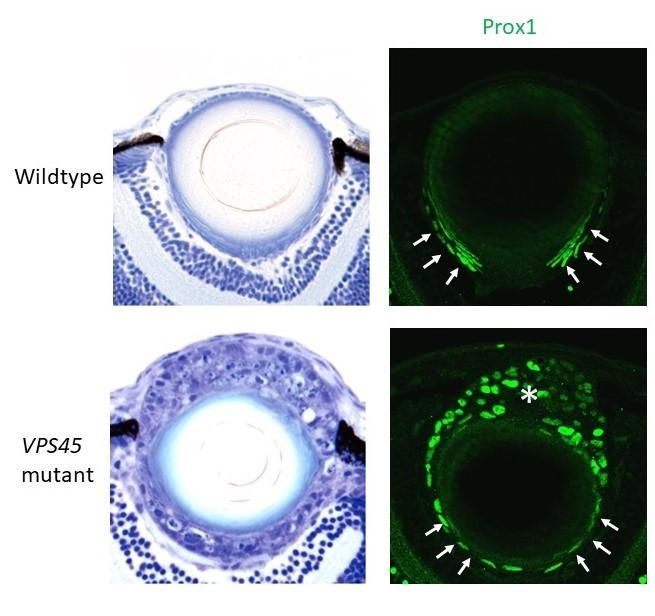

Wildtype lens development (top) compared to the VPS45 mutant (bottom). Fiber cell differentiation is indicated in green.

OIST

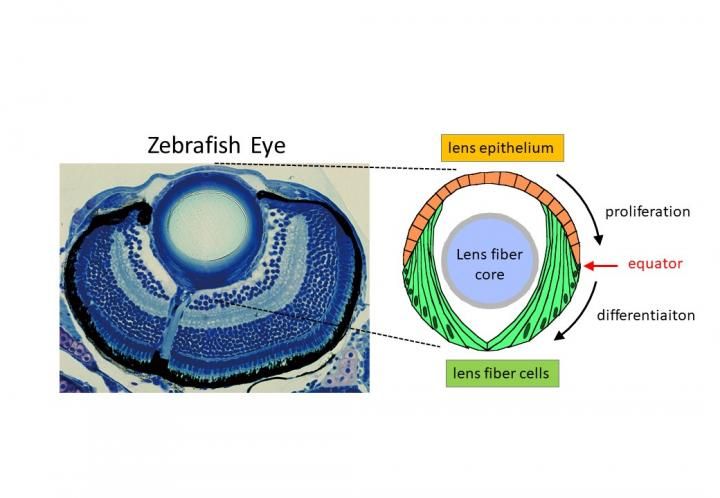

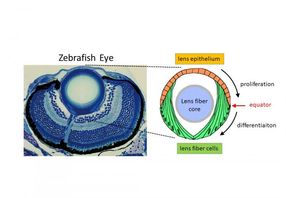

Diagram of the zebrafish lens. The red arrow points to the lens equator.

OIST

The team conducted their experiments using zebrafish, whose eye structure is fundamentally conserved across vertebrates, including humans. Their findings grant new insight into the complex process of cell differentiation.

"Scientists are curious to know how such an elegant structure is constructed by a genetic program," said Prof. Ichiro Masai, principal investigator of the Developmental Neurobiology Unit at OIST.

Besides demystifying lens development, the research may someday help uncover the pathology behind secondary cataracts, the most common complication of human cataract surgery.

A complement to known regulators

The spherical lens is mostly composed of lens fiber cells arranged in a tightly packed core. Lens epithelial cells cover the outermost surface of the front half of the lens, facing out from the body. As the lens epithelial cells proliferate, they migrate backwards, differentiate into lens fiber cells, and integrate into the existing lens fiber core.

The switch from one cell type to the other occurs during this migration, when epithelial cells cross a distinct boundary known as the "equator." Molecular cues push the cells to differentiate into lens fiber cells once they've crossed this line. One crucial cue is FGF. While FGF boosts lens fiber differentiation, Masai wondered if there were a complementary system that repressed it.

"The switch from epithelial into fiber cells occurs very precisely at the equator -- I thought there must be some tuning mechanism to ensure the equator-specific onset," said Masai. "Maybe, once epithelial cells cross the equator, they are relieved of this inhibitory mechanism and allowed to differentiate."

Researchers in the OIST Developmental Neurobiology Unit maintain a living library of mutant zebrafish for studies like this. Among hundreds of mutants, they selected one with uniquely abnormal lens development. Lens epithelial cells usually line up to form a single continuous layer, but in the mutants the cells pile up in a haphazard mass. That's because a mutated gene causes lens epithelial cells to differentiate independent of FGF exposure, and without having to cross the equator.

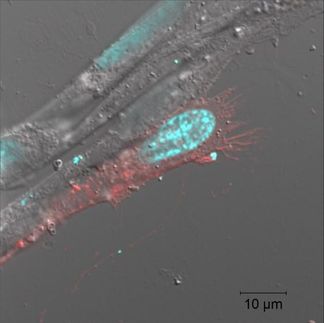

The gene normally encodes a protein known as "vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 45," or VPS45. VPS45 helps to shuttle incoming materials through the cell, directing them to specialized organelles for degradation or back to the cell membrane for recycling. Recent studies suggest this trafficking system modulates signaling pathways within the cell, which in turn, regulate developmental processes.

When the gene is mutated, however, normal lens development becomes disrupted. Specific signals that maintain lens epithelial cells are suppressed, while signals that promote fiber cell differentiation are enhanced.

Application in basic biology and cataract surgery

Masai's study is the first to describe a mechanism for lens fiber differentiation that is independent of FGF. He and his colleagues now aim to better understand how VPS45 regulates cellular signaling in the developing lens, and how those signals work together to support healthy development. Their research could eventually lead to medical interventions for when the process goes awry.

In the new study, for instance, the scientists found that a signaling pathway called TGF-ß became enhanced in the mutant zebrafish and caused abnormal lens development. TGF-ß signaling has also been shown to contribute to secondary cataracts, but scientists don't yet understand why.

During cataract surgery, a patient's cloudy lens is replaced with an artificial one. The operation restores the patient's vision, but can also prompt an innate healing response in lens epithelial cells. In an effort to mend the wound, the cells transform into myofibroblastic cells or lens fiber cells and consequently cloud the patient's brand-new lens. With a deeper understanding of factors driving lens development, scientists could circumvent secondary cataracts before they set in.

"Once we understand this underlying mechanism," said Masai, "we could develop a therapy to inhibit the pathological process of secondary cataracts."