Better scaffolds help scientists study cancer

Testing treatments for bone cancer tumors may get easier with new enhancements to sophisticated support structures that mimic their biological environment, according to Rice University scientists.

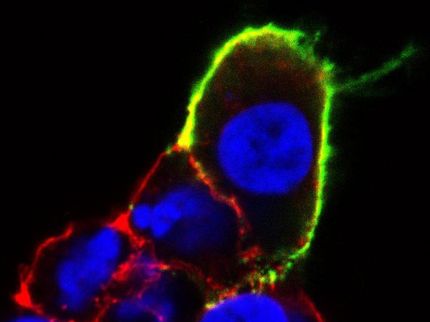

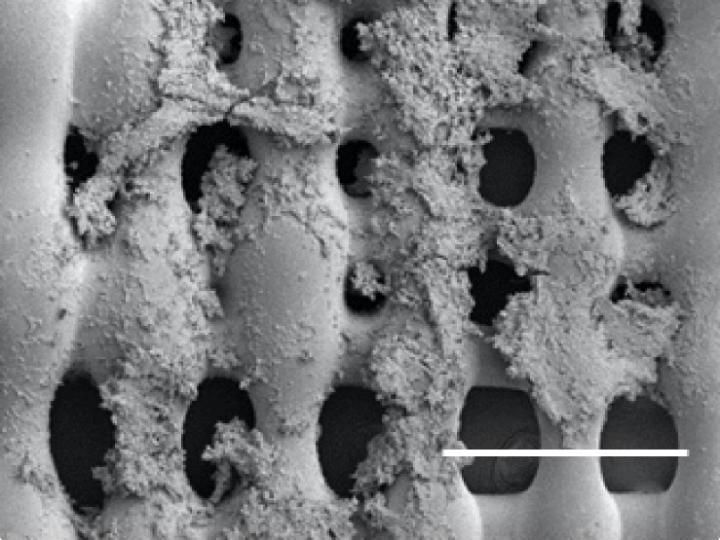

Sarcoma (bone cancer) cells proliferate on the surface of a 3-D printed scaffold created at Rice University. Experiments at Rice showed that the size of pores in the scaffold, which mimics the extracellular matrix in bone, and the pores' orientation make a difference in how cells proliferate in the presence of a flowing fluid, like blood.

Mikos Research Group/Rice University

A team led by Rice bioengineer Antonios Mikos has enhanced its three-dimensional printed scaffold to see how Ewing's sarcoma (bone cancer) cells respond to stimuli, especially shear stress, the force experienced by tumors as viscous fluid such as blood flows through bone. The researchers determined the structure of a scaffold, natural or not, has a very real effect on how cells express signaling proteins that help cancer grow.

The size and shape of pores and scaffold porosity -- the percent of empty space in a structure created by pores -- can impact cell attachment, alter the permeability of media and nutrients and facilitate cell migration, according to the researchers. The scientists said 3-D printing allows them to get closer than ever to mimicking the architecture of real bone.

The scaffold itself is special, according to Mikos. The bone-like printed polymer contains pores of varying sizes to constrain fluids that flow through and apply varying degrees of shear stress to the tumor cells, depending on the scaffold's orientation in relation to the flow.

"We aim to develop tumor models that can capture the complexity of tumors in vitro and can be used for drug testing, thus providing a platform for drug development while reducing the associated cost," Mikos said. He noted that by varying the scaffold architecture, they can change the mechanical environment through which fluids flow and the magnitude of shear stress exerted on tumor cells.

Flat sections of scaffold were printed with pores in one of three sizes: 0.2, 0.6 and 1 millimeter. Three layers of each were stacked to make each 3-D scaffold, and these were seeded with tumor cells and placed in a flow perfusion reactor that mimics the push and pull of fluids and tissues in a biological environment. This makes simulations much more realistic than growing cells in a flat petri dish, Mikos said.

The researchers found that cells proliferated far better under flow than in conditions with no fluid flow. When the fluid began to flow, layers with the smallest pores, which restrict permeability, showed significantly more proliferation. They also found that under flow, cells increased their production of insulin-like growth factor protein (IGF-1), a ligand on the surface of sarcoma cells and part of the signaling pathway that plays a critical role in resistance to chemotherapy. Additionally, the orientation of the 0.2, 0.6 and 1 millimeter pore sizes played a role in how much IGF-1 the cells produced.

They suspected that the combination of shear stress and scaffold orientation prompted different levels of protein production.

The researchers now plan to refine their scaffold-printing process to study metastasis and test tumors' response to drugs.

Original publication

Jordan E. Trachtenberg, Marco Santoro, Cortes Williams, Charlotte M. Piard, Brandon T. Smith, Jesse K. Placone, Brian A. Menegaz, Eric R. Molina, Salah-Eddine Lamhamedi-Cherradi, Joseph A Ludwig, Vassilios I. Sikavitsas, John P Fisher, and Antonios G. Mikos; "Effects of shear stress gradients on Ewing sarcoma cells using 3D printed scaffolds and flow perfusion"; ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng.; 2017