Targeting Parkinson's-linked protein could neutralize 2 of the disease's causes

Advertisement

Researchers report they have discovered how two problem proteins known to cause Parkinson's disease are chemically linked, suggesting that someday, both could be neutralized by a single drug designed to target the link.

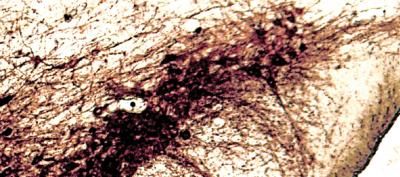

Dopamine-making cells in a mouse brain are shown.

Sung-ung Kang/Johns Hopkins Medicine

The investigators' new experiments build on evidence reported in 2011 that reducing the amount of a protein called PARIS in mice with the rodent equivalent of Parkinson's disease protects against the loss of dopamine-making neurons.

Since then, according to Ted Dawson, M.D., Ph.D. , professor of neurology and director of the Institute for Cell Engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, the research team suspected PARIS was linked chemically to other important Parkinson's proteins. "In this study, we were able to confirm that suspicion," he says.

Dawson explains that a hallmark of Parkinson's disease is the death of brain cells that produce the signaling molecule, or neurotransmitter, dopamine. Dopamine depletion, in turn, causes the classic symptoms of Parkinson's disease, such as tremors, muscle stiffness and lack of muscle coordination. Mutations in the gene for a protein called Parkin are known to cause the death of dopamine neurons; less commonly, defects in another protein, PINK1, can have the same effect.

In mouse experiments done in collaboration with researchers at Mayo Clinic in Florida, Dawson's team investigated whether both proteins might act through a single intermediary: PARIS.

In their 2011 study, Dawson and his collaborators had used mice and human brain tissue to find that Parkin adds a chemical tag known as ubiquitin to PARIS that signals other proteins to break it down.

To find out whether PINK1 and PARIS have a similar relationship, the researchers ran biochemical tests on purified proteins that revealed that PINK1 and PARIS interact. Dawson says the results revealed that while PINK1's normal role is to add a chemical tag known as a phosphate group to a certain spot on the PARIS protein, defective forms of PINK1 linked to Parkinson's disease cannot add that tag.

The phosphate addition, he says, kicks off a chain of events that ultimately leads to the dismantling of the PARIS protein, Dawson says, a cause-and-effect relationship his team verified by reducing the amount of PINK1 in lab-grown human cells, which led to a threefold increase in the amount of PARIS. Similarly, reducing the amount of PINK1 made in living mice by more than 80 percent led to a doubling in the amount of PARIS present.

In another experiment, the research team ramped up PINK1 production in lab-grown human cells and found that the resulting increase in cell death was alleviated if PARIS levels also increased. But if PINK1 was tweaked to eliminate the sites where PARIS normally adds a phosphate group, PARIS was unable to rescue the cells.

Since both Parkin and PINK1 protect brain cells by causing PARIS' breakdown, Dawson suggests that defects in either could be remedied if a treatment can be found that hobbles PARIS. "Mutations in the genes for both Parkin and PINK1 have now been linked to Parkinson's disease," he says. "Parkin is a particularly big player that seems to be at fault in many inherited cases; it's also inactivated in sporadic cases of the disease. So a drug targeting PARIS could potentially help many patients."

More than 1 million people in the United States live with Parkinson's disease. The disease gradually strips away motor abilities, leaving people with a slow and awkward gait, rigid limbs, tremors, shuffling and a lack of balance. Its causes are not well-understood. Currently available treatments, such as medications and deep brain stimulation, can alleviate symptoms but do not cure it or slow its progression.

Dawson emphasizes that clinical application of their discovery must await not only further studies in animals, but also years of drug design and clinical research. But he says their discovery has the potential to simplify and focus the development of better treatments.