Plant regulatory proteins 'tagged' with sugar

New work from Carnegie's Shouling Xu and Zhiyong Wang reveals that the process of synthesizing many important master proteins in plants involves extensive modification, or "tagging" by sugars after the protein is assembled. Their work uncovers both similarity and distinction between plants and animals in their use of this protein modification. It is published by Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

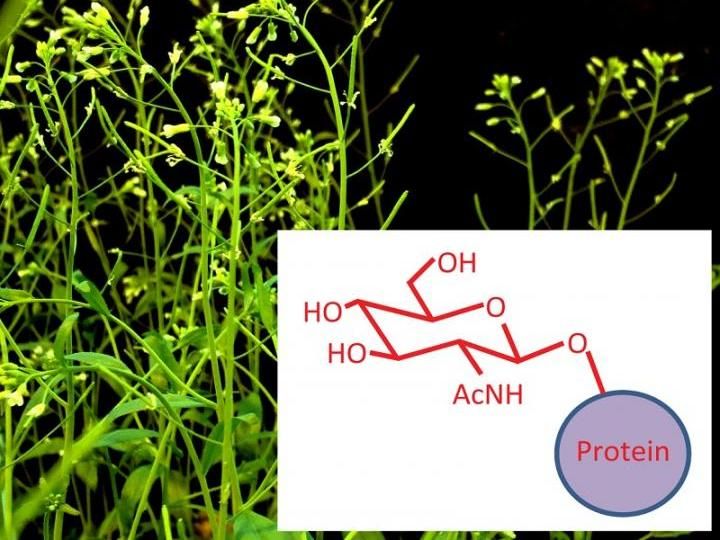

This is an illustration showing how a sugar molecule is attached to the protein when it undergoes the O-GlcNAcylation modification process.

Courtesy of Shouling Xu and Zhiyong Wang.

The blueprint for making all proteins is encoded in DNA. The genetic code tells the cellular protein-making apparatus the correct order in which to string together the amino acids that are the building blocks of every protein. Often, after their DNA code has been translated into the amino acid chain, newly synthesized proteins are further modified with different chemical moieties.

A common form of post-translational modification in animal cells has the tongue-twisting name of O-GlcNAcylation (pronounced oh-gluck-nakel-ation). It is a process by which certain amino acids in proteins get attached to a sugar molecule, and this modification impacts a wide array of cellular functions. In animals, changes to this process are associated with neurodegeneration, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. Embryos lacking the enzyme that accomplishes this modification cannot survive.

It was already known that O-GlcNAcylation takes place in plant cells, too. Plants in which the process is impeded show defects in light response, flower development, root growth, and leaf structure, among other things. However, much about which actual plant proteins undergo this modification had remained mysterious until now.

Xu and Wang collaborated with scientists of UCSF and China in identifying plant proteins that undergo this post-production, sugar-adding modification. A number of these affected proteins have regulatory functions that perform the same or similar functions in plants and animals. Many also perform developmental and physiological tasks that are unique to plants, such as flower development and responses to specific plant hormones.

"We identified 262 proteins that are modified by this process," Xu explained. "Furthermore our study provides the framework for a network of O-GlcNAcylation modification in plants, which will help us understand how the functions of these various proteins--and hence the growth processes they control--are regulated according to the availability of sugar in the cells."

"This is a big breakthrough for plant science," said Carnegie Plant Biology Director Sue Rhee. "Shouling and Zhiyong and their colleagues have opened up a whole new area of exploration that will advance our understanding of plant cellular biology."

Most read news

Organizations

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.