Pathogens may evade immune response with metal-free enzyme required for DNA replication

Some bacterial pathogens, including those that cause strep throat and pneumonia, are able to create the components necessary to replicate their DNA without the usually required metal ions. This process may allow infectious bacteria to replicate even when the host's immune system sequesters iron and manganese ions in an attempt to slow pathogen replication. A new study describes a novel subclass of metal-free ribonucleotide reductase enzymes used by these bacteria, an understanding of which could drive the development of new, more effective antibiotics.

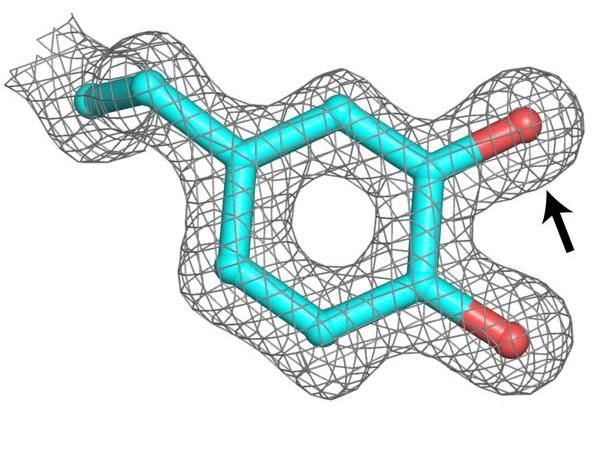

A metal-free ribonucleotide reductase--an enzyme required for DNA replication--from bacterial pathogens uses a post-translationally modified amino acid (pictured) to initiate an essential DNA biosynthesis reaction. The modification (indicated by arrow) is essential for initiation of ribonucleotide reduction. This metal-free enzyme could allow microbes associated with strep throat and pneumonia infections to more effectively proliferate during iron/manganese limitation imposed by the human immune system.

Gavin Palowitch, Penn State

"Every organism uses ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) enzymes to make the nucleotide building blocks needed for DNA replication and repair," said Amie Boal, assistant professor of chemistry and of biochemistry and molecular biology at Penn State and the lead author of the paper. "Because RNRs are essential, they are validated drug targets for some cancers and viral infections, but they have not yet been exploited as drug targets in pathogenic bacteria. One of the goals of our work is to better understand the cofactors required by RNRs to function, which will hopefully inspire the creation of new, potent antimicrobial drugs that can inhibit the enzyme."

RNRs perform very complex chemistry to convert ribonucleotides--the building blocks of RNA, which are present in the cell--into deoxyribonucleotides--the building blocks of DNA. All known RNRs used during aerobic metabolism require a metal ion cofactor, which acts as a powerful oxidizing agent to drive the conversion. In their new study, the team of researchers have now identified and described a new subclass of RNR that is capable of performing this process without the aid of a metal ion in the bacterial pathogens that cause strep throat, pneumonia, rheumatic fever, and other diseases.

"Requiring a trace-metal cofactor is the Achilles heel of an RNR, especially in pathogenic bacteria," said Gavin Palowitch, Ph.D. candidate in biochemistry, microbiology, and molecular biology at Penn State and coauthor of the study. "When a pathogen invades your body, one of the things that your immune system can do is try to deprive it of iron and manganese ions in an attempt to slow reproduction. If you have a way to make DNA that doesn't rely as much on a metal cofactor, that's a novel tactic for evading the immune response."

The researchers showed that this new subclass of RNR is able to use a modified amino acid instead of a metal ion as the oxidizing agent that drives the creation of DNA nucleotides. It remains unknown whether a metal is required for initial synthesis of the modified amino acid and then lost. But the study establishes that the modification does require a separate protein for its installation.

"The need for another activating protein is critical for thinking about inhibiting this enzyme with antibiotic drugs," said Boal. "Protein-protein interactions are really attractive targets for disruption by small molecule therapeutics."

Original publication

Other news from the department science

Get the life science industry in your inbox

By submitting this form you agree that LUMITOS AG will send you the newsletter(s) selected above by email. Your data will not be passed on to third parties. Your data will be stored and processed in accordance with our data protection regulations. LUMITOS may contact you by email for the purpose of advertising or market and opinion surveys. You can revoke your consent at any time without giving reasons to LUMITOS AG, Ernst-Augustin-Str. 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany or by e-mail at revoke@lumitos.com with effect for the future. In addition, each email contains a link to unsubscribe from the corresponding newsletter.

Most read news

More news from our other portals

Last viewed contents

Cosmetic_dentistry

SEC-MALS-complete-System | SEC systems | Wyatt Technology

Immunoglobulin_superfamily

List_of_subjects_in_Gray's_Anatomy:_X._The_Organs_of_the_senses_and_the_Common_integument

Fleur_de_sel

Growth_hormone_deficiency