Protein Associated with Parkinson’s Travels from Brain to Gut

A new laboratory study provides clues on a particular pathway of “alpha-synuclein” diffusion

Researchers of the German Center for neurodegenerative diseases (DZNE) have found that “alpha-synuclein”, a protein involved in a series of neurological disorders including Parkinson’s disease, is capable of travelling from brain to stomach and that it does so following a specific pathway. Donato Di Monte and co-workers report on this in the journal “Acta Neuropathologica”. Their study, carried out in rats, sheds new light on pathological processes that could underlie disease progression in humans.

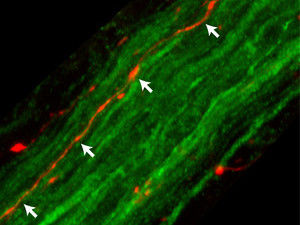

In a laboratory study, DZNE researchers have found that "alpha-synuclein", a protein involved in Parkinson's disease, is capable of travelling from the brain to the stomach using the vagus nerve as a conduit. This image shows fibers of the rat vagus nerve (green); one of these fibers (orange-red, indicated by white arrows) contains alpha-synuclein on its way to the stomach.

DZNE/Ayse Ulusoy

Alpha-synuclein occurs naturally in the nervous system, where it plays an important role in synaptic function. However, in Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies and other neurodegenerative diseases termed “synucleinopathies”, this protein is accumulated within neurons, forming pathological aggregates. Distinct areas of the brain become progressively affected by this condition. The specific mechanisms and pathways involved in this widespread distribution of alpha-synuclein pathology remain to be fully elucidated. Clinical and experimental evidence suggests however that alpha-synuclein - or abnormal forms of it - could “jump” from one neuron to another and thus spread between anatomically interconnected regions.

Alpha-synuclein lesions have also been observed within neurons of the peripheral nervous system, such as those in the gastric wall. In some Parkinson’s patients, these lesions were detected at early disease stages. “Based on these intriguing observations, it has been hypothesized that the pathological process underlying Parkinson’s disease may actually start in the gastrointestinal tract and then move toward the brain”, Professor Di Monte says. “Our present approach was to look at this long-distance transmission of alpha-synuclein from the opposite perspective, investigating the possibility that alpha-synuclein may travel from the brain to the gut.”

Experimental setting

Di Monte and co-workers tested this hypothesis in a laboratory study. With the help of a tailor-made viral vector they triggered production of human alpha-synuclein in rats. The virus transferred the blueprint of the human alpha-synuclein gene specifically into neurons of the midbrain, which then began producing large quantities of the foreign protein. “Some forms of Parkinson’s disease are associated with an overproduction of alpha-synuclein. Thus, our model mimics events of likely relevance to humans”, Di Monte notes.

Tissue analysis by collaborators at Purdue University revealed that, after its midbrain expression, the protein was capable of reaching nerve endings in the gastric wall. Further work in the Di Monte’s laboratory established the precise pathway used by human alpha-synuclein to complete its journey from the brain to the stomach. The protein first moved from the midbrain to the “medulla oblongata”, the lowest brainstem region; in the medulla oblongata, it was detected within neurons whose long fibers form the “vagus nerve”. Fibers of the vagus nerve connect the brain to a variety of internal organs; travelling within these fibers, human alpha-synuclein was ultimately able to reach the gastric wall about six months after its initial midbrain expression. Progressive accumulation of human alpha-synuclein within gastric nerve terminals was accompanied by evidence of neuronal damage.

From brain to gut along specific routes

“Our study shows that alpha-synuclein is able to travel quite far through the body, passing from one neuron to another and using long nerve fibers as conduits”, Di Monte says. “Our findings do not rule out the possibility that diseases associated with alpha-synuclein may originate in the gut. This may happen in some patients. Our results indicate however, that if pathological alpha-synuclein is detected outside the brain, this does not necessarily mark the site where the disease started.”

The study also reveals a preferential route of alpha-synuclein transmission via the vagus nerve. The vagus nerve is composed of two kinds of fibers: 10-20% of fibers are “efferents” whereas the remaining 80-90% are “afferents”. Efferent fibers are projections of motor neurons that control the gut’s motility. In contrast, afferent fibers relay sensory input from the gut to the brain. For its journey from the brain to the stomach, alpha-synuclein only used the less abundant efferent vagal projections.

“This is quite remarkable”, Di Monte says. “It shows that transmission of alpha-synuclein is not just a matter of anatomical connections. Certain neurons appear to have a particular propensity to take up, transfer and accumulate alpha-synuclein. We don’t know the precise mechanisms underlying this selective neuronal behavior. It is likely, however, that these mechanisms could explain why certain neuronal populations and brain regions are particularly susceptible to alpha-synuclein pathology. This is something we intend to look at in further studies.”