Deadly sleeping sickness set to be eliminated in 6 years

Gambian sleeping sickness could be eliminated in 6 years thanks to University of Warwick research Combination of active screening and tsetse fly traps the key to quick elimination Without changing current strategy, elimination isn't predicted until the next century

This image shows deploying targets in DRC.

Inaki Tirados

Gambian sleeping sickness - a deadly parasitic disease spread by tsetse flies - could be eliminated in six years in key regions in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), according to new research by the University of Warwick.

Kat Rock and Matt Keeling at the School of Life Sciences, with colleagues in DRC and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, have calculated the impact of different intervention strategies on the population dynamics of tsetse flies and humans - establishing which strategies show the most promise to control and eliminate the disease.

They found that a two-pronged approach - integrating active screening and vector control - could substantially speed up the elimination of Gambian sleeping sickness in high burden areas of DRC.

Without changing current strategy, elimination might not happen until the 22nd century.

The researchers, who work as part of the Neglected Tropical Disease Modelling Consortium, used complex mathematical models to compare the efficacy of six key strategies and twelve variations within two areas of Kwilu province (within former Bandundu province), DRC.

Previous work by the same group indicates that high-risk people are often missed from active screening. The new model concludes that improved active screening - making sure that all people are screened equally, regardless of risk factor - may allow elimination as a public health problem between 2023 and 2031.

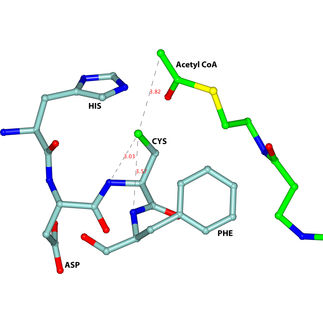

If vector control strategies - using "tsetse targets" coated with insecticide to attract and kill flies - are added, this elimination goal is likely to be achieved within four years when coupled with any screening approach.

If DRC adopts any of the new strategies with vector control, transmission would probably be broken within six years of launching the new program in these areas - and over 6000 new infections could be averted between 2017 and 2030.

Strategies which rely only on self-reporting of illness and screening of low-risk individuals are unlikely to lead to elimination of sleeping sickness transmission by 2030, and delay elimination until the next century.

Gambian sleeping sickness, or Gambian human African trypanosomiasis, is caused by a parasite called Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, carried by tsetse flies in Central and West Africa. Without treatment, the disease usually results in death.

In recent years, programmes have performed intense active and passive screening to decrease disease incidence. A few areas have also combined these medical interventions with vector control. But some high prevalence regions of DRC have not achieved the reductions in disease seen in other parts of Africa. Other strategies for elimination will also include reinforced passive screening, new diagnostic tools and improved drugs.

In 2012, the World Health Organization set two public health goals for the control of Gambian sleeping sickness, a parasitic disease spread by the tsetse fly. The first is to eliminate the disease as a public health problem and have fewer than 2000 cases by 2020; while the second goal is to achieve zero transmission around the globe by 2030.

Kat Rock comments:

"We found that vector control has great potential to reduce transmission and, even if it is less effective at reducing tsetse numbers as in other regions, the full elimination goal could still be achieved by 2030.

"We recommend that control programmes use a combined medical and vector control strategy to help combat sleeping sickness."

The research, "Predicting the Impact of Intervention Strategies for Sleeping Sickness in Two High-Endemicity Health Zones of the Democratic Republic of Congo", is published in PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases.