Tugging at cells with molecules and light

A new method for cellular stimulation

Advertisement

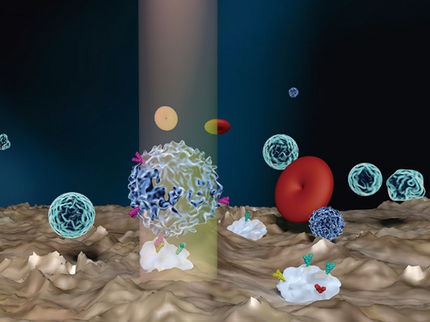

Everyone is made up of approximately 100 trillion cells – if they were laid end to end, they would circle the globe 60 times. Most of these cells arise from mitosis and differentiation of a single egg cell. To orientate themselves, they constantly explore their environment and communicate with their neighbours while they adhere to other cells or surfaces. Two working groups from the fields of chemistry and biophysics at Kiel University have discovered a new method for stimulating cells, thereby increasing their adhesion.

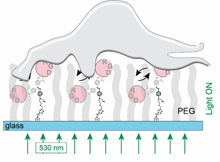

Irradiation with green light from below induces a vibration of the signalling molecules (RGD). This mechanical stimulus causes the cells to adhere to the surface.

Rainer Herges

Cells are permanently under attack by bacteria that are attempting to infiltrate them. By contrast, useful bacteria aid digestion or live peacefully on human skin. Cells must communicate continuously and probe their environment to identify friend or foe, or to differentiate themselves from their neighbouring cells. This is why they seek out direct contact with other cells or to their environment. ‘If individual cells are floating in a solution and encounter a surface, they first probe the area to determine whether it is a suitable location to settle. If this is the case, they extend protein sensors to attach themselves. Other cells follow suit, which creates cellular tissue,’ explains Rainer Herges, professor at the Institute of Organic Chemistry.

Cells adhere faster if they are stimulated

Research has long shown that cells respond selectively to certain surface structures and their chemical composition. There are indications that, in addition to static stimuli, dynamic processes such as movements and mechanical forces also have an attracting effect on cells. If, for example, a fine needle is used to tug at cells, this stimulates them to increase their adhesion. ‘However, this is not a very subtle, controlled method, since a large number of different cellular processes are affected,’ reports Christine Selhuber-Unkel, professor for biocompatible nanomaterials at the Institute for Materials Science at Kiel University.

The method that Selhuber-Unkel and Herges now have discovered for stimulating cells is much more sophisticated. They bind chemical recognition structures (so-called RGDs), which are recognised by cells, to surfaces. However, these signalling molecules do not stand stiff on the surface; instead, they can be moved with light. Tiny molecular switches are incorporated into the tether that binds the RGDs to the surfaces. These molecules bend back and forth approximately 1,000 times per second when they are irradiated with green light. ‘This vibration is transferred to the RGDs, which in turn “pluck” at the cells. The cells appear to perceive this type of stimulation: they adhere faster and more strongly to the surface,’ explains Selhuber-Unkel. This adhesion strength is measured using an atomic force microscope. The fact that there is increased production of adhesion proteins also indicates that the cells react to this stimulus.

Light as a ‘nanoscalpel’?

The discovery by the researchers in Kiel could trigger a multitude of potential applications. The molecular vibrators can be directly incorporated into cell membranes, which would allow cells to be controlled with light. ‘Use of light as a type of “nanoscalpel” is also conceivable in the long-term; light could be employed to perform extremely precise, microscopic, surgical interventions’, Herges continues.

Research on how to use light to indirectly stimulate cells via molecular switches has been a topic at the Collaborative Research Centre 677 ‘Function by Switching’ since several years. ‘Using light for stimulation has a number of advantages. Firstly, it can be switched on and off in a controlled way,’ explains Herges, the head of the SFB. ‘Moreover, using a laser cells can be irradiated with a resolution of 300 nanometres to detect which areas on the cell are responsible for adhesion. Thereby, we can elucidate the mechanisms of cellular adhesion.’ Interdisciplinary cooperation was initiated by the framework of the CRC 677. Michelle Holz and Grace Suana from Rainer Herges’ working group in the organic chemistry institute synthesised the switching molecules and surfaces. Laith F. Kadem from Christine Selhuber-Unkel’s working group conducted the cell experiments.