Promising transport molecule for steroid medications discovered

When the word steroids comes up, a lot of people think of doping. It is much less well known that steroids are used in the treatment of many diseases, such as asthma, neurodermatitis, multiple sclerosis, and Crohn’s Disease. Scientists at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) and Jacobs University in Bremen have now found a possible way that steroids can exert their effect in the human body in a gentler and more efficient way.

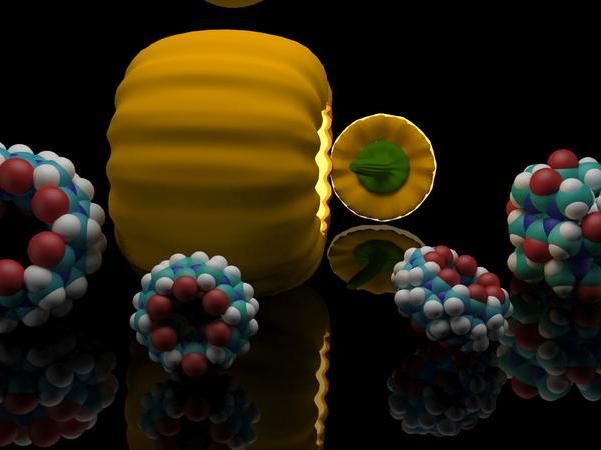

Jacobs University / Khaleel Assaf

It is difficult for steroids to dissolve in water, and they require corresponding excipients so that they can be used as medications. These molecules, also called active substance transporters or synthetic hosts, enclose the respective active substance in a cavity and dissolve it in the body. For steroids, it has been primarily cyclodextrins, ring-shaped glucose molecules, which have carried out this task. Their disadvantage: They accelerate the dissolution process so much that some people tolerate the taking of steroids poorly. With the cucurbiturils, the scientists from Karlsruhe and Bremen have now identified a very promising transport molecule that can be used to reduce such undesirable side effects.

“We have now found that the host class of cucurbiturils has a higher affinity for the steroids that are decisive for medical use than do the cyclodextrins,” explains Dr. Frank Biedermann, scientist at the Institute of Organic Chemistry at KIT. Cyclodextrins are relatively large molecules, which have a flexible form that on the one hand makes them more adaptable but also causes them to collapse more readily. In order to achieve the necessary water solubility, therefore, a higher dose of the active substance and excipient is needed. This increases the rate of adverse effects of the corresponding medication. In addition, cyclodextrins have a greater tendency to bond with thinner molecular chains, such as cholesterol, which is not relevant as an active substance.

Based on tests with the hormones testosterone and estradiol, the inflammation inhibitor cortisol, and the muscle relaxants pancuronium and vercuronium, experts have demonstrated that cucurbiturils that contain steroid are substantially more stable and increase the water solubility of their guest molecule more. In addition, they can function as an active substance depot, because they also remain stable in blood serum and gastric acid and release steroids more slowly in the body. The new host group is biocompatible and can be used in lower doses and more selectively. Consequently, steroid-based drugs could work better, their side effects could be reduced, and the costs of production could drop.

“With the aid of cucurbiturils, it could be possible in the future to develop new and more efficient forms of administration for steroid drugs,” of that Professor Werner Nau, expert in supramolecular chemistry at Jacobs University in Bremen, is convinced. But, in the estimation of the two scientists, it is not just pharmacology but also basic biological research that can profit from the new active substance transporters. That is because cucurbiturils, in combination with an indicator dye, also make it possible to observe the interaction between steroids and enzymes in real time on their way through the body.

Exploring these varied options for using the molecules in more detail is the goal of follow-up projects at KIT and Jacobs University, which are being subsidized by the German Research Foundation (DFG). “The more precisely we understand the route and the mode of action of the steroids, the more selectively we can discontinue them where they are no longer needed,” explains Nau. In a follow-up study, for example, doctoral researcher Alexandra Irina Lazar is investigating how steroids can be broken down again in the environment after leaving the body.