‘Cellbots’ chase down cancer, deliver drugs directly to tumors

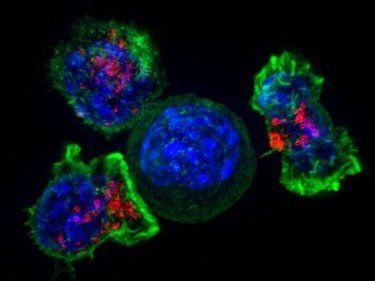

Killer T cells (green and red) surrounding a cancer cell.

Image by Alex Ritter, Jennifer Lippincott Schwartz, Gillian Griffiths/National Institutes of Health

UC San Francisco scientists have engineered human immune cells that can precisely locate diseased cells anywhere in the body and execute a wide range of customizable responses, including the delivery of drugs or other therapeutic payloads directly to tumors or other unhealthy tissues. In experiments with mice, these immune cells, called synNotch T cells, efficiently homed in on tumors and released a specialized antibody therapy, eradicating the cancer without attacking normal cells.

In addition to delivering therapeutic agents, synNotch cells can be programmed to kill cancer cells in a variety of other ways. But synNotch cells can also carry out instructions that suppress the immune response, offering the possibility that these cells could be used to treat autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes or to locally suppress immune system rejection of transplanted organs.

“SynNotch is a universal molecular sensor that allows us to program immune cells as if they were microscopic robots," said Wendell Lim , PhD, chair and professor of cellular and molecular pharmacology at UCSF, Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, and member of the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center . “They can be customized with different features and functions, and when they detect the appropriate signals in a diseased tissue, they can be triggered to deploy diverse therapeutic weapons.”

The new research broadens and deepens previous research on synNotch T cells in Lim’s laboratory , which has shown, among other things, that the synNotch sensor platform can be used to create custom “logic gates” in T cells that allow them to recognize and kill cancer cells, while protecting closely related healthy cells. These cellular “AND gates” require two separate conditions to be met in target cells before the T cells take steps to eliminate the target.

T cells are highly motile, and roam throughout the body seeking out diseased or infected cells. A form of T cell therapy known as CAR (Chimeric Antigen Receptor) T therapy has been widely publicized for its unprecedented success in treating a form of blood cancer known as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or ALL.

But because CAR T therapy largely relies on the “built-in” sensing and response properties of T cells, some of which can be deleterious, it can have serious side effects. Moreover, because T cells are often unable to overcome properties of tumors that suppress immunity, CAR T therapy has so far not been effective against the solid tumors that affect the breast, prostate, brain, lungs and other organs. Lim said that the synNotch technology developed at UCSF can be used on its own, but can also be added to CAR T cells to sidestep many of that therapy’s current limitations.

SynNotch is so called because it is the product of several synthetic alterations of Notch, a protein involved in cell-to-cell communication in diverse organisms that is especially crucial for normal development. First of all, the synNotch receptor acts as a “universal sensor” – it has a component protruding from the T cell that can be swapped out to specifically recognize many different types of disease signals. And synNotch’s other end, inside the cell, is an “effector” component that can be engineered to cause the cell to carry out diverse responses.

The research team at the UCSF Center for Systems and Synthetic Biology , led by postdoctoral fellow and first author Kole T. Roybal , PhD, demonstrated the versatility of synNotch T cells in several ways.

Original publication

Kole T. Roybal, Jasper Z. Williams, Leonardo Morsut, Levi J. Rupp, Isabel Kolinko, Joseph H. Choe, Whitney J. Walker, Krista A. McNally, Wendell A. Lim; "Engineering T Cells with Customized Therapeutic Response Programs Using Synthetic Notch Receptors"; Cell; 2016