Singapore scientists develop DNA-altering technology to tackle diseases

Researchers in Singapore have developed a new protein that can alter DNA in living cells with much higher precision than current methods.

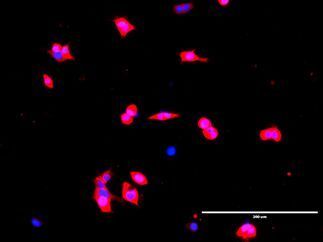

The iCas protein (stained in red) created by Singapore scientists is shown moving into the cells' nuclei to make changes to the DNA (stained in blue). The pink region indicates that iCas is positioned at the DNA to perform its function.

A*STAR's Genome Institute of Singapore

The ability to alter DNA accurately will open more doors in the development of personalised medicine that could help to tackle human diseases that currently have few treatment options. Examples of diseases that have unmet therapeutic needs include neurodegenerative diseases like Huntington's disease, muscular dystrophies, and blood disorders like sickle cell anaemia.

This new protein, named iCas, can be easily controlled by an external chemical input and thus solves some of the problems with CRISPR-Cas*, the existing gold-standard for DNA altering. For example, existing Cas enzymes may sometimes alter places in the DNA that result in dire consequences. With iCas, users now have the ability to control enzyme activity and thus minimize unintended DNA modifications in the cell.

Leading the joint research team is Dr Tan Meng How, Senior Research Scientist of Stem Cell & Regenerative Biology at the GIS, and Assistant Professor at NTU's School of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering.

"DNA is like an instruction manual that tells living cells how to behave, so if we can rewrite the instructions in this manual, we will be able to gain control over what the cells are supposed to do," explained Dr Tan. "Our engineered iCas protein is like a light switch that can be readily turned on and off as desired. It also outperforms other existing methods in terms of response time and reliability."

How DNA altering works

To ensure that DNA is precisely altered, which is required in many biomedical and biotechnological applications, the activity of the Cas protein must be tightly regulated.

The chemical that switches the iCas protein on or off is tamoxifen, a drug commonly used to treat and prevent breast cancer. In its absence, iCas is switched off with no changes made to the DNA. When switched on with tamoxifen, iCas will then edit the target DNA site.

In the study, iCas was found to outperform other chemical-inducible CRISPR-Cas technologies, with a much faster response time and an ability to be switched on and off repeatedly.

The higher speed at which iCas reacts will enable tighter control over exactly where and when DNA editing takes place. This is useful in research or applications that demand precise control of DNA editing.

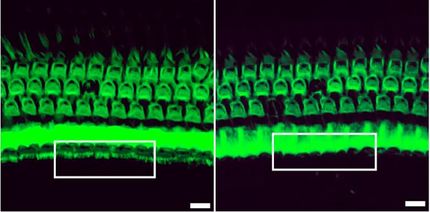

For example, in studies of cell signalling pathways or vertebrate development, iCas can precisely target a subset of cells within a tissue (spatial control) or to edit the DNA at a particular developmental stage (temporal control).

"The iCas technology developed by Dr Tan is an exciting addition to the growing CRISPR toolbox. It enables genome editing in a precisely controlled manner, thus opening new doors for applications of the CRISPR technology in basic and applied biological research," said Dr Huimin Zhao, the Steven L. Miller Chair Professor of the Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering faculty at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (UIUC).

GIS Executive Director Prof Ng Huck Hui added, "This development allows the researchers to have precision control for more accurate DNA editing, and it can help researchers engineer cells with new properties or repair diseased cells with mutated DNA."

Prof Teoh Swee Hin, Chair of NTU's School of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering, said, "DNA editing is an exciting field with many potential uses in the treatment of diseases. NTU has been active in research in the area of gene sequencing and bioengineering over the past years and this work by Dr Tan and his Singapore team will add to the growing body of knowledge in cell engineering for medicine."

Original publication

Kaiwen Ivy Liu, Muhammad Nadzim Bin Ramli, Cheok Wei Ariel Woo, Yuanming Wang, Tianyun Zhao, Xiujun Zhang, Guo Rong Daniel Yim, Bao Yi Chong, Ali Gowher, Mervyn Zi Hao Chua, Jonathan Jung, Jia Hui Jane Lee & Meng How Tan; "A chemical-inducible CRISPR-Cas9 system for rapid control of genome editing"; Nature Chemical Biology; 2016