New hope for Zika treatment found in large-scale screen of existing drugs

Advertisement

Scientists report that a specialized drug screen test using lab-grown human cells has revealed two classes of compounds already in the pharmaceutical arsenal that may work against mosquito-borne zika virus infections.

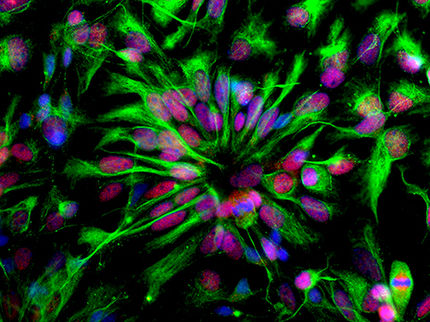

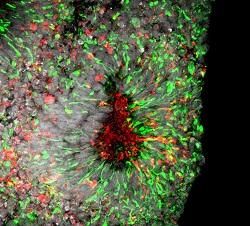

This image shows Zika virus infection in cell death in human forebrain organoids.

Xuyu Qian, Johns Hopkins University

In a summary of their work the investigators say they screened 6,000 existing compounds currently in late-stage clinical trials or already approved for human use for other conditions, and identified several compounds that showed the ability to hinder or halt the progress of the Zika virus in lab-grown human neural cells.

The research collaboration includes teams from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, the National Institutes of Health and Florida State University.

"It takes years if not decades to develop a new drug," says Hongjun Song , Ph.D., director of the Stem Cell Program in the Institute of Cell Engineering at Johns Hopkins. "In this sort of global health emergency, we don't have that kind of time."

"So instead of using new drugs, we chose to screen existing drugs," adds Guo-li Ming , M.D., Ph.D., professor of neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "In this way, we hope to create a therapy much more quickly."

The new findings are an extension of previous work by the research team, which found that Zika mainly targets specialized stem cells that give rise to neurons in the brain's outer layer, the cortex. The researchers observed Zika's effects in two- and three-dimensional cell cultures called "mini-brains," which share structures with the human brain and allow researchers to study the effects of Zika in a more accurate model for human infection.

In the current study, the research team exposed similar cell cultures to the Zika virus and the drugs one at a time, measuring for indicators of cell death, including caspase-3 activity, a chemical marker of cell death, and ATP, a molecule whose presence is indicative of cell vitality.

Typically, after Zika infection, the damage done to neural cells is "dramatic and irreversible," says Hengli Tang , Ph.D., professor of biological sciences at Florida State University. However, some of the compounds tested allowed the cells to survive longer and, in some cases, fully recover from infections.

Further analysis of the surviving cells, says Ming, showed that the promising drugs could be divided into two classes: neuroprotective drugs, which prevent the activation of mechanisms that cause cell death, and antiviral drugs, which slow or stop viral infection or replication. Overall, Song says, three drugs showed robust enough results to warrant further study: PHA-690509, an investigational compound with antiviral properties; emricasan, now in clinical trials to reduce liver damage from hepatitis C virus and shown to have neuroprotective effects; and niclosamide, a drug already used in humans and livestock to combat parasitic infections, which worked as an antiviral agent in these experiments.

Song cautioned that the three drugs "are very effective against Zika in the dish, but we don't know if they can work in humans in the same way." For example, he says, although niclosamide can safely treat parasites in the human gastrointestinal tract, scientists have not yet determined if the drug can even penetrate the central nervous system of adults or a fetus inside a carrier's womb to treat the brain cells targeted by Zika.

Nor, he says, do they know if the drugs would address the wide range of effects of Zika infection, which include microcephaly in fetuses and temporary paralysis from Guillain-Barre syndrome in adults.

"To address these questions, additional studies need to be done in animal models as well as humans to demonstrate their ability to treat Zika infection," says Ming. "So we could still be years away from finding a treatment that works."

The researchers say their next steps include testing the efficacy of these drugs in animal models to see if they have the ability to combat Zika in vivo.