Core proteins exert control over DNA function

The protein complex that holds strands of DNA in compact spools partially disassembles itself to help genes reveal themselves to specialized proteins and enzymes for activation, according to Rice University researchers and their colleagues.

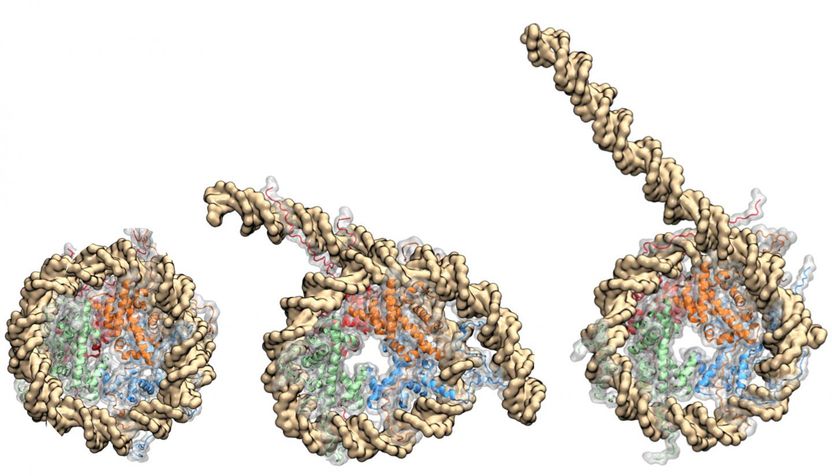

Rice University scientists simulated a nucleosome coiled in DNA to discover the interactions that control its unwinding. The DNA double helix binds tightly to proteins (in red, blue, orange and green) that make up the histone core, which exerts control over the exposure (center and right) of genes for binding.

Wolynes Lab/Rice University

The team's detailed computer models support the idea that DNA unwrapping and core protein unfolding are coupled, and that DNA unwrapping can happen asymmetrically to expose specific genes.

The study of nucleosome disassembly was conducted by Rice theoretical biological physicist Peter Wolynes, former Rice postdoctoral researcher Bin Zhang, postdoctoral researcher Weihua Zheng and University of Maryland theoretical chemist Garegin Papoian. The research is part of a drive by Rice's Center for Theoretical Biological Physics (CTBP) to understand the details of DNA's structure, dynamics and function.

The spools at the center of nucleosomes, the fundamental unit of DNA organization, are histone protein core complexes. Nucleosomes are buried deep within a cell's nucleus. About 147 DNA base pairs (from the more than 3 billion in the human genome) wrap around each histone core 1.7 times. The double helix moves on to spiral around the next core, and the next, with linker sections of 20 to 90 base pairs in between.

The structure helps squeeze a 6-foot-long strand of DNA in each cell into as compact a form as possible while facilitating the controlled exposure of genes along the strand for protein expression.

The spools consist of two pairs of heterodimers, macromolecules that join to form the core. The core is stable until genes along the DNA are called upon by transcription factors or RNA polymerases; the researchers' goal was to simulate what happens as the DNA unwinds from the core, making itself available to bind to outside proteins or make contact with other genes along the strand.

The researchers used their energy landscape models to simulate the nucleosome disassembly mechanism based on the energetic properties of its constituent DNA and proteins. The landscape maps the energies of all the possible forms a protein can take as it folds and functions. Conceptual insights from energy landscape theory have been implemented in an open-source biomolecular modeling framework called AWSEM Molecular Dynamics, which was jointly developed by the Papoian and Wolynes groups.

Wolynes said most studies elsewhere treated the histone core as if it were rigid and irreversibly disassociated when DNA unwrapped. But more recent experimental studies that involved gently pulling strands of DNA or used fluorescent resonance energy transfer, which measures energy moving between two molecules, showed the protein core is flexible and does not completely disassemble during unwrapping.

In their simulations, the researchers found the core changed its shape as the DNA unwound. Without DNA, they found the histone core was completely unstable in physiological conditions.

Their simulations showed that histone tails - the terminal regions of the core proteins - play a crucial role in nucleosome stability. The tails are highly charged and bind tightly with DNA, keeping its genomic content from being exposed until necessary. Their models predicted a faster unwrapping for tail-less nucleosomes, as seen in experiments.

The nucleosome study is part of a larger effort both by Papoian at Maryland and by Wolynes with his colleagues at CTBP to understand the mechanics of DNA, from how it functions to how it reproduces during mitosis. Wolynes said the new study and another new one by his lab on DNA during mitosis represent the opposite ends of the size scale.

"We can understand things at each end of the scale, but there's a no-man's land in between," he said. "We'll have to see whether the phenomena in the present-day no-man's land can be understood. I don't believe in magic; I believe they eventually will."