Reading between the genes

Advertisement

Our genes decide about many things in our lives – what we look like, which talents we have, or what kind of diseases we develop. For a long time dismissed as “junk DNA”, we now know that also the regions between the genes fulfil vital functions. They contain a complex control machinery with thousands of molecular switches that regulate the activity of our genes. Until now, however, regulatory DNA regions have been hard to find. Scientists around Patrick Cramer at the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen and Julien Gagneur at the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have now developed a method to find regulatory DNA regions which are active and controlling genes.

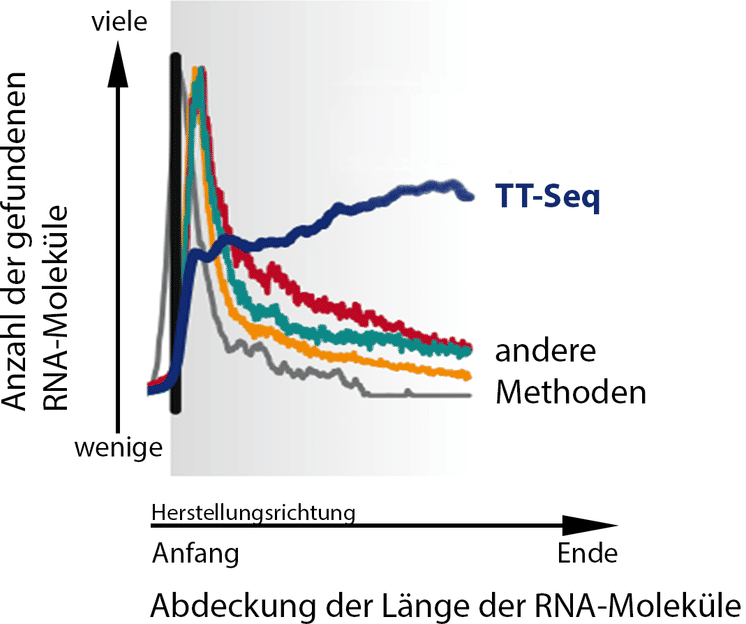

In contrast to older methods, TT-Seq (dark blue) allows scientists to gain a very consistent picture of all RNA molecules in the cell.

Margaux Michel, Patrick Cramer / Max-Planck-Institut für biophysikalische Chemie

The genes in our DNA contain detailed assembly instructions for proteins, the “workers” carrying out and controlling virtually all processes in our cells. To ensure that each protein fulfils its tasks at the right time in the right place of our body, the activity of the corresponding gene has to be tightly controlled. This function is taken over by regulatory DNA regions between the genes, which act as a complex control machinery. “Regulatory DNA regions are essential for development in humans, tissue preservation, and the immune response, among others,” explains Patrick Cramer, head of the Department for Molecular Biology at the MPI for Biophysical Chemistry. “Furthermore, they play an important role in various diseases. For example, patients suffering from cancer or cardiovascular conditions show many mutations in exactly those DNA regions,” the biochemist says.

When regulatory DNA regions are active, they are first copied into RNA. “The resulting RNA molecules have a great disadvantage for us researchers though: The cell rapidly degrades them, thus they were hard to find until now,” reports Julien Gagneur, who recently moved with this group from the Gene Center of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich to the TUM. “But exactly those short-lived RNA molecules often act as vital molecular switches that specifically activate genes needed in a certain place of our body. Without these molecular switches, our genes would not be functional.”

An anchor for short-lived molecular switches

Björn Schwalb and Margaux Michel, members of Cramer’s team, as well as Benedikt Zacher, scientist in Gagneur’s group, have now succeeded in developing a highly sensitive method to catch and identify even very short-lived RNA molecules – the so-called TT-Seq (transient transcriptome sequencing) method. In order to catch the RNA molecules, the three junior researchers used a trick: They supplied cells with a molecule acting as a kind of anchor for a couple of minutes. The cells subsequently incorporated the anchor into each RNA they made during the course of the experiment. With the help of the anchor, the scientists were eventually able to fish the short-lived RNA molecules out of the cell and examine them.

“The RNA molecules we caught with the TT-Seq method provide a snapshot of all DNA regions that were active in the cell at a certain time – the genes as well as the regulatory regions between genes that were so hard to find until now,” Cramer explains. “With TT-Seq we now have a suitable tool to learn more about how genes are controlled in different cell types and how gene regulatory programs work,” Gagneur adds.

In many cases, researchers have a pretty good idea which genes play a role in a certain disease, but do not know which molecular switches are involved. The scientists around Cramer and Gagneur are hoping to be able to use the new method to uncover key mechanisms that play a role during the emergence or course of a disease. In a next step they want to apply their technique to blood cells to better understand the progress of a HIV infection in patients suffering from AIDS.