Multiplexed Morse signals from cells

How many sorts, in how many copies? The biochemical processes that take place in cells require specific molecules to congregate and interact in specific locations. A novel type of high-resolution microscopy developed at the Max Planck Institute for Biochemistry in Martinsried and Harvard University already allows researchers to visualize these molecular complexes and identify their constituents. Now they can also determine the numbers of each molecular species in these structures. Such quantitative information is valuable for the understanding of cellular mechanisms and how they are altered in disease states.

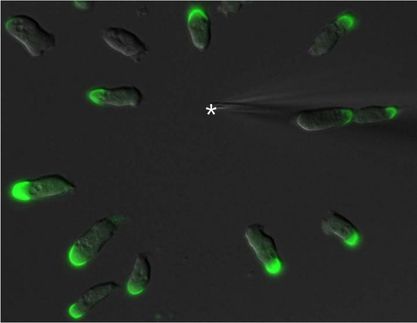

The novel high-resolution microscopy technique qPAINT allows the quantification of single molecules. For the detection of different molecules, laser beams in different wavelength are used.

Maximilian Strauss © MPI of Biochemistry

To an outside observer major construction sites often look quite chaotic, as hundreds of workers come together in constantly changing combinations, moving back and forth between teams engaged in tasks at different locations. Observing what goes on in biological cells often confuses researchers too, as they try to understand how subcellular operations are organized. Even biological macromolecules are so tiny that they can only be visualized with the help of highly sensitive fluorescent markers, usually attached to an antibody that binds specifically to a particular type of molecule. Ralf Jungmann, who leads a research group devoted to Molecular Imaging and Bionanotechnology at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry and the Ludwig Maximilian University Munich, has progressively increased the versatility of this basic method, developing a method which he calls DNA-PAINT. This procedure makes it possible to sequentially visualize multiple cellular molecules and their interactions with high precision.

The flexibility of the method arises from the fact that the fluorescent compound and its target (the bound antibody) do not interact directly. Instead, each is coupled to a short DNA strand, and because their nucleotide sequences are complementary, the two strands fit together like the two halves of a zipper. This process of “hybridization” reveals the position of the target protein. Furthermore, the strength of the interaction between the DNA strands can be adjusted, such that they separate after a certain time, and the fluorescence signal ceases. Then, the fluorescent label is washed out of the fixed cell and, in a variant of DNA-PAINT called Exchange-PAINT, is replaced by the same fluorophore attached to a different DNA docking sequence, which recognizes its partner strand on a different cellular protein in the same structure.

In this way, one obtains a series of snapshots, each of which originates from a specific component of the same cellular structure. When the individual shots are superimposed, the result is a kind of high-resolution group portrait of the various molecular species that interact with each other and work together to carry out a particular biological process. But that’s not all the technique can do. In order to be able to image biological structures and processes in all their complexity, before joining the MPI for Biochemistry, Jungmann had worked on an extension of the method in the research group led by Peng Yin at Harvard’s Wyss Institute and Harvard Medical School in Boston.

The newly acquired ability to carry out quantitative analyses represents a further important step towards this goal. As Jungmann and his colleagues now report, qPAINT makes it possible for the first time to determine the numbers of each molecular species present in multisubunit complexes. The trick is to adjust the relative affinities of the complementary DNA strands such that the hybridized segments dissociate from one another after a preset time. The single strands can then interact once more, thus inducing a further burst of fluorescence.

The frequency of fluorescence signals in turn serves as a measure of the number of interacting molecules present in the structure of interest. The researchers hope that the novel procedure will find application in many areas of cell biology, not least because it is more economical than other types of high-resolution microscopy. “Knowledge of the numbers of copies of a specific molecule involved in a given biological process is also important in the case of pathological perturbations,” says Jungmann, who is one of two joint first authors of the new study. “In many such cases, the changes that occur are quantitative rather than qualitative in nature.”