Urinary tract infection: How bacteria nestle in

Almost every second woman suffers from a bladder infection at some point in her life. Also men are affected by cystitis, though less frequently. In eighty percent of the cases, it is caused by the intestinal bacterium E. coli. It travels along the urethra to the bladder where it triggers painful infections. In “Nature Communications” researchers from the University of Basel and the ETH Zurich explain how this bacterium attaches to the surface of the urinary tract via a protein with a sophisticated locking technique, which prevents it from being flushed out by the urine flow.

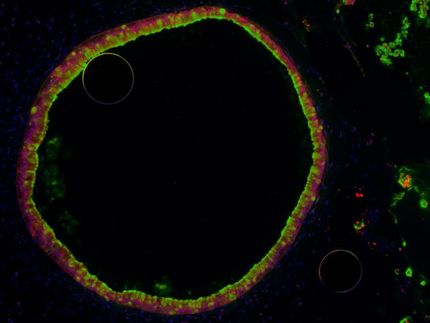

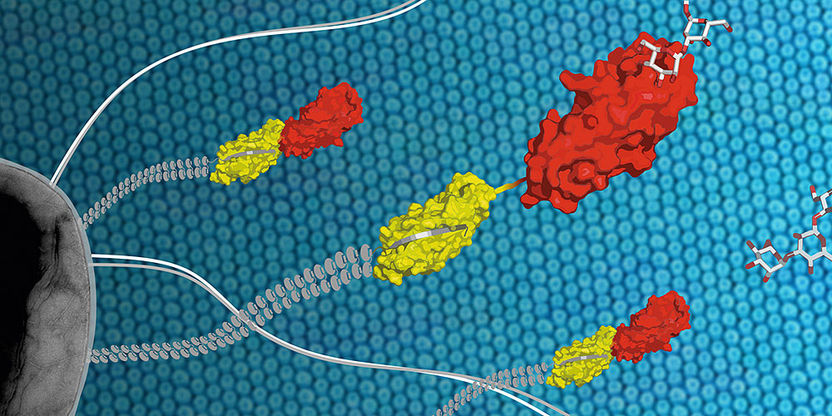

Using the protein FimH (yellow/red) located at the tip of long protrusions, the bacterial pathogen E. coli (grey) attaches to cell surfaces of the urinary tract (Image: Maximilian Sauer, ETH Zürich).

Maximilian Sauer, ETH Zürich

Many women have already experienced how painful a bladder infection can be: a burning pain during urination and a constant urge to urinate are the typical symptoms. The main cause of recurrent urinary tract infections is a bacterium found in the normal flora of the intestine, Escherichia coli. The bacteria enter the urinary tract, attach to the surface and cause inflammation.

The teams of Prof. Timm Maier at the Biozentrum and Prof. Beat Ernst at the Pharmazentrum of the University of Basel, along with Prof. Rudolf Glockshuber from the Institute of Molecular Biology and Biophysics at the ETH Zurich, have now discovered how bacteria adhere to the urinary tract under urine flow via the protein FimH and subsequently travel up the urethra.

Intestinal bacterium adheres to the cell surfaces with the protein FimH

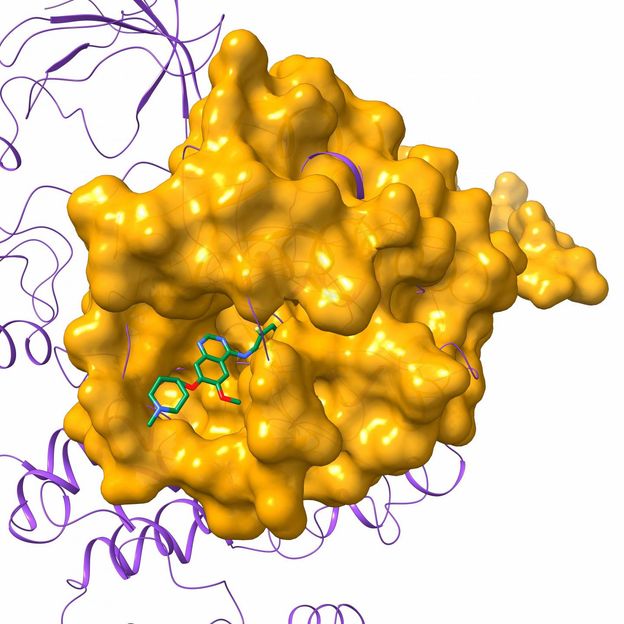

The pathogen has long, hairlike appendages with the protein FimH at its tip, forming a tiny hook. This protein, which adheres to sugar structures on the cell surface, has a special property: It binds more tightly to the cell surface of the urinary tract the more it is pulled. As strong tensile forces develop during urination, FimH can protect the bacterium from being flushed out.

“Through the combination of several biophysical and biochemical methods, we have been able to elucidate the binding behavior of FimH in more detail than ever before”, says Glockshuber. In their study, the scientists have demonstrated how mechanical forces control the binding strength of FimH. “The protein FimH is composed of two parts, of which the second non-sugar binding part regulates how tightly the first part binds to the sugar molecule“, explains Maier. “When the force of the urine stream pulls apart the two protein domains, the sugar binding site snaps shut. However, when the tensile force subsides, the binding pocket reopens. Now the bacteria can detach and swim upstream the urethra.”

Drugs against FimH to combat urinary tract infections

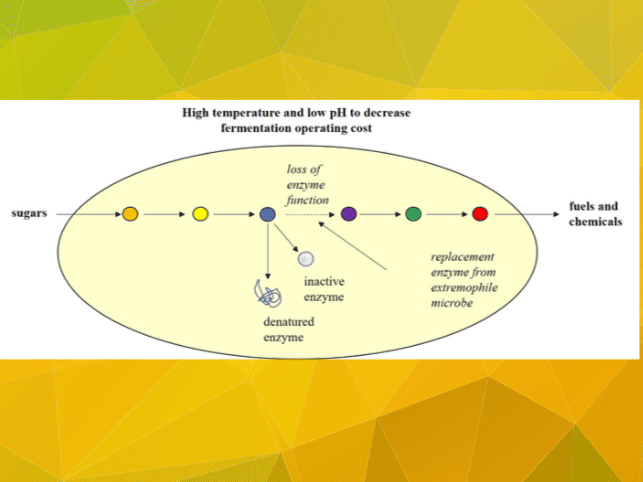

Urinary tract infections are the second most common reason for prescribing antibiotics. Yet, in times of increasing antibiotic resistance, the focus moves increasingly to finding alternative forms of treatment. For the prevention and therapy of E. coli infections, drugs that could prevent the initial FimH attachment of the bacteria to the urinary tract could prove to be a suitable alternative, as this would make the use of antibiotics often unnecessary.

This opens up the possibility of reducing the use of antibiotics and thus preventing the further development of resistance. Prof. Ernst, from the Pharmazentrum of the University of Basel, has been working intensively on the development of FimH antagonists for many years. The elucidation of the FimH mechanism supports these efforts and will greatly contribute to the identification of a suitable drug.